Imagine you are an interviewer looking to hire a new intern. After several rounds of interviews, you are left with two strong, intelligent and charismatic candidates. There is a catch, though: one of them is diagnosed with Autism. Would you choose the candidate with a severe mental disorder over the other equally talented one? Most people are quick to dismiss the candidate with Autism. We take a contrarian view.

As a society, we are undeniably becoming much more accepting of mental disorders. Our colleagues and friends are more comfortable openly discussing their depression, anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder than they would have been in decades past. Even those who experience more severe issues, like Autism, Asperger’s, and Motor/Tic disorders (among them Tourette’s syndrome) live in a more accepting and open society than generations before them. That said, there is still work to be done.

Archaic social norms in the business world?

When it comes to the professional environment however, things are a little different. Living with a mental disorder is not something one tends to brag about when searching for a job. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, some 70 to 80 percent of psychiatric-diagnosed individuals are unemployed. A recent study by the Canadian Health Association reveals that only one out of 1000 pass the first candidate screening.

Fortunately, not all people with mental disorders remain jobless. Rejected by recruiters, some of them have the energy to start their own enterprise. Attention-deficit disorders (ADD), dyslexia, obsessive compulsive disorders (OCD) are all entrepreneur-friendly conditions. Pierre Peladeau, the founder of the Quebecor empire, openly discusses his manic depression. George Soros, the man behind Soros Fund Management – one of the most profitable hedge funds in history – suffered from a lifetime mental distress. He compared himself to “a sick person with a parasitic fund swelling inexorably inside his body.”

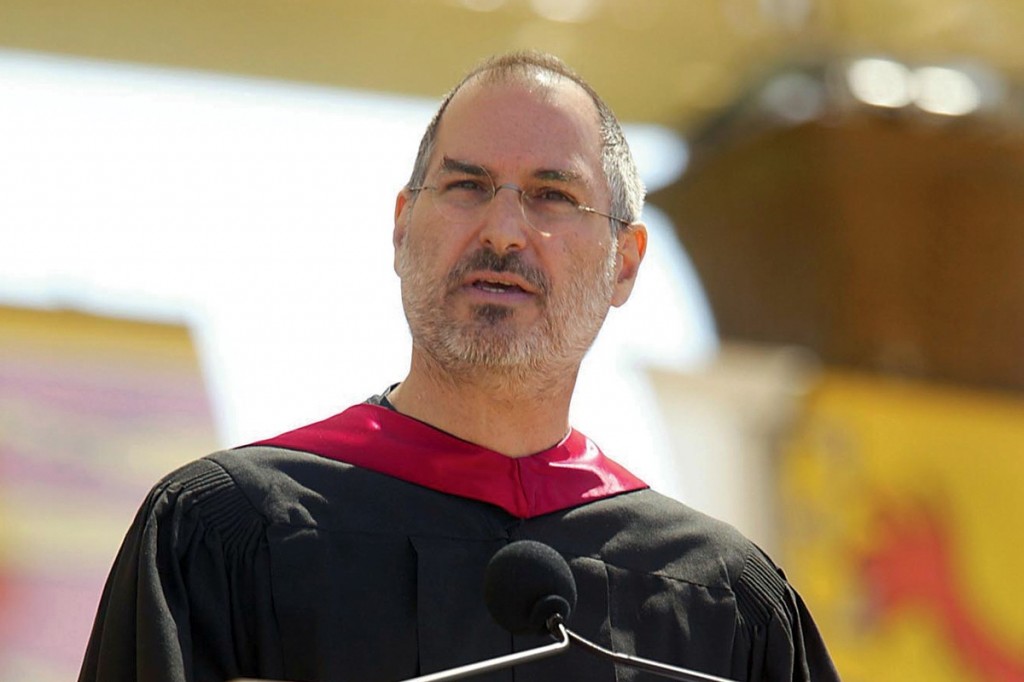

Some of recent influential entrepreneurs also show many traits of mental particularities. Mark Zuckerberg is well-known for his “touch of Asperger’s” while Steve Jobs’ obsession with details is often described as OCD. Winston Churchill had bipolar disorder, Henry Heinz was OCD, Isaac Newton was described as psychotic.

The benefits of diversity

Despite the apparent challenges they face, many mentally ill individuals succeed in turning their perceived “weakness” into their biggest strength. People suffering from mental disorders think differently. They have different approaches and logic schemes. And this is exactly why they can be an asset for a company.

Rob Lachenauer, CEO and a co-founder of Banyan Family Business Advisors, witnessed a great change and improvement in his corporate culture after hiring a woman suffering from mental illness. Her fresh ideas and new perspectives reenergized and unified the management team. “Over the past few years, she has become not only a core member of our team, but a large part of the glue that holds the firm together” explains Lachenauer in Why I Hired an Executive with a Mental Illness. “What she brought to the table was deep self-awareness, a keen mind, and profound emotional intelligence.”

There are numerous examples of people who live with mental disorders and mental illness and excel in the business world. What’s more, their condition can even contribute to their success.

Discovering a passion for finance

In 2004, during his residency in neurology at Stanford Hospital, 32-year-old Michael Burry discovered a vivid interest for financial markets. It soon became his new obsession. He would work all day on his medical studies and spend his nights reading about finance. He had always been very passionate about his precise fields of interest and showed little interest in social interactions.

When his son was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, Burry started reading about its common symptoms: difficulties with engaging in social routines, empathizing with others, and controlling feelings. He was especially intrigued by two of the symptoms on the list: above-average intelligence and a tendency to have very specialized fields of interest or hobbies. He could no longer deny the obvious. Was his own success due to his particular mental condition? Without a doubt.

Asperger’s syndrome allowed him to understand financial markets like no one else at the time. Despite his limited social capacities, he managed to convince enough investors to participate in his new hedge fund. In 2005, he became particularly interested in understanding how subprime-mortgage bond worked and soon discovered “the extension of credit by instrument.” In short, he was one of the first and few investors to realize that “lenders had lost it.” Banks were creating aberrant financial instruments to justify their massive lending to decreasingly creditworthy borrowers.

His special interest and perseverance not only allowed him to foresee the subprime crisis, but also to find a way to bet against the system as mortgage bonds were impossible to short. Michael Lewis describes in great depth in The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine how he came up with the idea of using credit-default swaps on subprime mortgage bonds – a form of insurance against the default of specific mortgage bonds.

Burry’s success story is not an isolated case. The job requirements for computer programmer, statistician or quantitative analyst look incredibly similar to the list of symptoms of Autism and Asperger’s syndrome. Tech firms are seeking workers with incredible attention to detail, while hedge funds look for candidates with phenomenal quant skills. It is absolutely about time that we open our doors to people living with mental disorders.

The only clear barrier between the mentally ill and the mentally healthy comes from preconception spread in society – infamous social norms. Employers would benefit greatly if they overcome these prejudices. Real change may manifest itself as a balance between a embracing different way of thinking and pursuing unique diversity in the workplace.