Last spring, in a darkened dorm room, I sat with four friends for four hours watching a ferry travel down a canal. Fueled by some leftover snacks and a strange sense of endurance, we settled in and followed along as the ferry made stops at various small towns in Norway, slowly making its way to Dalin.

Of course, this viewing wasn’t entirely genuine—we clicked on the Netflix movie (“Slow TV: The Telemark Canal”) mostly as a joke and watched plenty of it passively. But even though the video is literally just a real-time documentary about a canal journey, with Norwegian folk music interspersed throughout, we watched it for quite a long time.

Somehow, we were far from the first to watch the video. Actually, we weren’t even close. When it originally aired in Norway in 2012, more than 1.3 million people tuned in. Somehow, a video of a boat traveling down a canal for 12 hours was compelling enough for almost a third of the country to turn on their televisions. This is just the tip of the iceberg for Slow TV. This genre of television, first popularized in Norway, has gradually adopted a worldwide audience through its depictions of knitting, salmon fishing, and sheep shearing.

We’ll dive deep into the world of knitting, then from midnight, we’ll turn down the pace, if that’s even possible

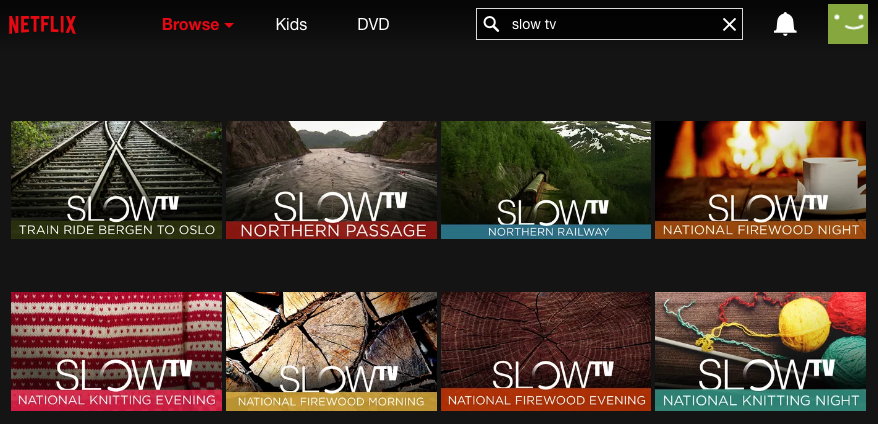

Netflix offers 8 of the specials, ranging in length from 2 to 12 hours, and including three specials about firewood: “National Firewood Morning,” “National Firewood Evening,” and “National Firewood Night.” None of them are just videos of fires burning, either. They cover the entire process: chopping the wood, collecting it, and interviews with the Norwegians who make this their lifestyle. Slow TV stands not just out as not just a strange outlier in the television scene, but as a complete anomaly.

Slow TV is in many ways a strange beast of a program. “National Firewood Night,” viewed by a fifth of the population when it aired, is based on a best-selling Norwegian book by Lars Myttling, Solid Wood: All About Chopping, Drying, and Stacking Wood—and the Soul of Wood Burning.

“National Knitting Night” was described by Sidsel Munal, a Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) representative, as “the feminine response to the firewood show.” The event was also pitched by a different representative. “We’ll dive deep into the world of knitting, then from midnight, we’ll turn down the pace, if that’s even possible”, Rune Moeklebust explained, “We’ll watch the arm of a sweater get longer and longer; it will be fascinating…but pretty strange TV.” There’s a lot going on in terms of describing Slow TV in those two quotes. I’ll just let them sink in. 1.3 million people tuned into the program when it aired in 2013.

The first Slow TV program, “Bergensbanen – minutt for minutt” depicted a 7-hour train journey from Bergen to Oslo and was described by The New Yorker as “iconic,” with Nathan Heller comparing the Slow TV phenomenon to a more American program: though half the population of Norway regularly tunes in to Slow TV, the final episode of “Seinfeld” only captured forty-one percent of US viewers.

Slow TV becomes less about watching television to let a curated plot and visuals pull viewers out of reality, and instead about watching television to escape into a world for its calm social presence

Part of what makes Slow TV so interesting is its unexpected ability to be quite entertaining. It offers a break from the relentless slew of perfectly curated entertainment that we most often see, television and film that’s designed to attract viewers through spectacle and beauty. Instead, Slow TV puts the mundanities of life forward, attracting viewers purely interested in something peaceful. This is a large part of why it’s become so popular in Nordic countries, where a culture that in many ways contrasts directly with the bustling nature of North American life lends itself to an audience interested in ten hours of people waiting for fish to bite.

As a result, Slow TV becomes less about watching television to let a curated plot and visuals pull viewers out of reality, and instead about watching television to escape into a world for its calm social presence. That means that the act of viewing Slow TV is different too, because you can’t really watch it like you would watch anything else. It’s television to put on in the background, like listening to rain sounds or static. And often, that comparison is the best way to understand how Slow TV works.

Somewhere, there’s a story to craft about the boat traveling down the canal, but that story isn’t going to be told to you: you’ll need to make it up

It’s also worth comparing Slow TV to the work of minimalist composer LaMonte Young, whose work similarly offers a media with no inherent meaning. His compositions, most famously “The Well-Tuned Piano,” a five-hour piano piece, are works of minimalist music with no readily apparent classical influences or stylizations. Yet they’re captivating, simply because their minimalism offers to the listener an opportunity to find meaning in the composition that must come entirely from themselves. To a lesser degree, Slow TV offers a similar experience, creating entertainment whose meaning exists only when attributed by the viewer. Somewhere, there’s a story to craft about the boat traveling down the canal, but that story isn’t going to be told to you: you’ll need to make it up.

Slow TV is, by definition, quite strange and foreign. But there’s plenty of it to dive into on Netflix, and its popularity in Norway makes it hard to ignore as an up-and-coming genre of television. If you do decide to watch some, I’d recommend turning the subtitles off. For me, at least, it’s more satisfying to watch without any understanding whatsoever of the context or dialogue of the show. It makes it that much more absurd as a genre, and gives a boost to the slow TV’s appeal as a backdrop to your own fantastically peaceful thoughts and emotions.