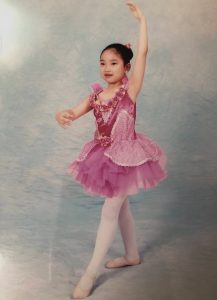

Every Friday night, Angelina Ballerina came to life on television. The show documented the adventures of one larger-than-life mouse who dreamt of becoming a prima ballerina. She was pink and British and ridiculous. As a child, I was obsessed. I would have my ballet flats ready in hand to dance when she danced, chest-puffed, flailing my body before the television in plight of grace.

At another time in my life, I dedicated myself to chess and spent an hour every week losing to my merciless father, yet still I remained convinced that I would one day master the game. Later, my brother and I took on the art of hand-pulled noodles and spent perhaps too much time with flour-caked hands, kneading and stretching dough, slapping it on the table as if we were master chefs in performance. The noodles would inevitably break, my mother would laugh, and we would then devour bowls that were only ever decent, but felt perfect nonetheless. We learned later that the skill supposedly takes ten years to master.

I’ve spent my first month at McGill and feel that time passes differently here; the weeks disappear before I realize they have begun, each moment embroiled with a future deadline and need to charge towards a specific end.

The days seemed longer when we were younger, when we could spend hours playing board games or learning a new skill, when we were asked what our hobbies were and encouraged to do things for the simple fact that we enjoyed them. I’ve spent my first month at McGill and feel that time passes differently here; the weeks disappear before I realize they have begun, each moment embroiled with a future deadline and need to charge towards a specific end.

Being students of McGill and motivated individuals, it is easy to feel that doing anything without productive value is a mere waste of time. The cultivation of hobbies seems useless, even indulgent. We feel the time we spend needs to be justified with measures of success and validation that we may later reap. I’ve realized that from a certain time in my life, while growing and navigating through the education system, I’ve become selfish with my actions. I am greedy for opportunities that will depict me as an individual who is passionate and a productive asset of society. It is now imperative for me to calculate how I can later capitalize on my time for a resume or CV, how I will craft my identity until it is no more than a set of marketable assets and experiences.

I fear for someone to ask me what my hobbies are, as I wouldn’t know what to say. I used to dance. I used to have a small but impressive rock collection. I used to lose myself in books, a feeling I have not felt in a long time. Like other writers have explored in the past, I often imagine crafting a new identity for myself: “I rock climb on the weekends and I spend my spare time fermenting cheese.” Or perhaps: “I practice yoga and enjoy foraging for wild mushrooms.”

Perhaps I have to admit there is little that completely consumes me anymore, the way things did when I was a kid. This past year, I read Little Women, a classic tale about the quaint lives of the four March sisters. I found myself jealous of their concentrated characters, their certainties of who they are. I envied to describe myself in the way the author, Louisa May Alcott, describes them in few, albeit powerful words.

Hobbies may only be a small aspect of the greater problem, but I feel they can help return a small morsel of my former, more adventurous self.

While I am often too willing to mold myself to whatever may guarantee success or practicality, the way they hate and love is intense and inspiring. Alcott describes Jo: “Every few weeks she would shut herself up in her room, put on her scribbling suit, and fall into a vortex, as she expressed it, writing away at her novel with all her heart and soul, for till that was finished she could find no peace.” It feels wrong that such a feeling is rare to me. Hobbies may only be a small aspect of the greater problem, but I feel they can help return a small morsel of my former, more adventurous self.

Research validates the numerous ways having a hobby can benefit our lives. A study conducted by the US National Library of Medicine demonstrated that time spent on leisure activities correlated with lower blood pressure and overall better physical health. Hobbies can also increase your productivity and work performance while decreasing levels of stress. They can ignite greater creativity and allow your mind to gain different perspectives while solving problems. While all these benefits are wonderful, these shouldn’t be the reasons that convince us, as this perspective, again, attempts to justify something that shouldn’t need justifying.

There is value in learning the flute even if we’re not going to be the best, but merely because we like the way it sounds

The definition of hobby is simple but telling: “An activity done regularly in one’s leisure time for pleasure.” Thus, perhaps we should recognize the value in ‘wasting time’ if it is spent doing something that brings us joy. There is value in learning the flute even if we’re not going to be the best, but merely because we like the way it sounds. There is value in painting a terrible painting. There is value in time spent detached from a future goal. Hobbies have the great power of slowing down time and bringing you to the present moment. Perhaps there is value in staying in that moment, lest we always exist several steps ahead.