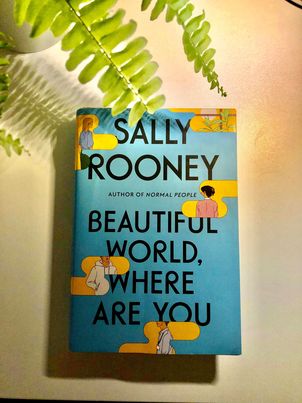

For all the authorial self-importance that seems to glow behind so much sleeper-hit autofiction, the question that these books ask all seem to be one and the same: what’s the point of reading the very book you’re reading? Or more broadly, what is the aim of the novel—the kind of novel where we expect a set of characters to spar spiritually and leave bruised but changed for the better by the last page—in a world where crises of unfathomable scale overlap, and there are no solid boundaries anywhere, between the smallest individual act and the big picture, of global political unrest, late capitalist dread, and environmental collapse? Or as Alice Kelleher, the protagonist in Sally Rooney’s “Beautiful World, Where Are You” asks on our behalf and about her own books, why do we care about these “sensitive little novels about ‘ordinary life’” when there is nothing ordinary about life except its volatility, unevenly distributed?

Of course, coming from the author of “Normal People” and “Conversations with Friends,” Alice’s question is partly Rooney’s as well. Christian Lorenzen once argued that “in autofiction there tends to be emphasis on the narrator’s or protagonist’s or authorial alter ego’s status as a writer or artist and that the book’s creation is inscribed in the book itself.” To be clear, “Beautiful World, Where Are You” only meets the first criterion—the book is, thankfully, not about its own writing, but Alice is functionally an authorial alter ego, a novelist contending with the fame (or infamy) accrued from her last few books, one of which has been adapted as a TV show (and, for Rooney, soon to be two). Alice, like how Rooney herself has wondered aloud before in interviews, is also contemplating the novel’s social (f)utility, the exhaustion not of its formal or experimental possibilities, but how galvanizing any politically-minded novel can be, whatever form it takes. What good is it to have a self-conscious author write about themselves from a remove, doing a bit of indirect self-diagnosis, and then putting it out in the world? How different is that, in terms of rousing people to action, from posting a rambling Twitter thread about surveillance capitalism? Where is the cure, the headrush of finding some impossible out?

Reading autofiction, or fiction that veers close to it, tends to make me feel like I’m stuck in an airplane, having somehow forgotten that I ever boarded, unsure I’ll ever land.

There are no clear answers to any of these questions, and that exasperating lack of an answer, that sigh after so much abstract fussing, even with someone who understands you, seems to be the very air that novels like this tend to breathe; at once prosaically smooth yet devoid of gusto, fatally aware of our lack of control over the atmosphere. Reading autofiction, or fiction that veers close to it, tends to make me feel like I’m stuck in an airplane, having somehow forgotten that I ever boarded, unsure I’ll ever land.

Rooney’s book, despite its themes and its Alice/Rooney conceit, is not some nihilistic anti-novel, nor are any of the other recent books that play with the idea of trivial lived experience as something both exhausting and sacred, charged with as much potential for constant social disaster as it is for a kind of private redemption. When I first saw copies of Rooney’s book and their titular question staring out at me like a grid of Zoom faces in the window display, the Internet-famous poet from Patricia Lockwood’s “No One Is Talking About This” and the literature professor from Jenny Offill’s “Department of Speculation”—you guessed it, authorial alter egos—answered for me. ‘They’re right here,’ they said. Your sister’s baby in your arms, the snow that makes the world look “blankly beautiful.”

The key word is “beauty,” how it has warped over time to represent garish consumerism, billboard idolatry, and a plastic world.

“Beautiful World, Where Are You,” seems to settle for the same answer. To elaborate on that answer: the old unshakeable aesthetic values that kept the experience of art priceless—making it, encountering it, believing in it—are about as hard to believe nowadays as the absolute moral truths of the Bible. The key word is “beauty,” how it has warped over time to represent garish consumerism, billboard idolatry, and a plastic world. Something—or, with arms flapping, everything—about this historical moment has stunted our spiritual and psychic growth, and strolling (or scrolling) through a world full of benign surfaces makes even youth seem like it was designed with planned obsolescence. It’s not a new thesis, but it’s precisely that sense of stagnation which animates the characters in this book to want more, to look under the surface of contemporary experience and find more than a godless LED glow.

The book follows two distant pairs of friends/lovers/ambiguous in-betweens: in the small town of Bellina, the rich and famous novelist Alice Kelleher and warehouse worker Felix Brady; in Dublin, the literary journal editor Eileen and political consultant Simon, who Eileen first had a crush on when she was 15 and he was 20 (though now everyone is in their late twenties and early thirties). The gaps in income and age make for some obvious class and sexual tensions, but Rooney’s sensibility shines in letting the bare fact of these circumstances inflict the damage over time—through reluctant resentments, barbed comments, confessional emails—rather than big outbursts. In a way, this has always been Rooney’s strength: sketching the outlines of a relationship between two misfits who don’t want their connection to be transactional but are forced into a taxing emotional calculus when faced with how, say, Alice is a millionaire writer who chose to move to a county town, and Felix is a warehouse worker who has no choice but to stay. One of them might jest that they both make a living stocking shelves, but the laugh would be forced, spent as fast as the impulse behind any wisecrack. Well, then. Another pint?

Classic Rooney so far. But what is different this time around is that Rooney, speaking through the imperfect medium of Alice, turns what might have been a novel dogged by self-pitying irony or lame metafiction into a novel that is at once an embrace and a rebuke of her own style, her own thematic concerns. Yes, it may be true that these contemporary novelists “know nothing about ordinary life.” Or that they “pretend to be obsessed with death and grief and fascism – when really they’re obsessed with whether their latest book will be reviewed in the New York Times.” But for all that Alice seems to hate these books and the impulse that drives her to write more of them, the emails exchanged between her and Eileen point to the kind of self-understanding that can only happen between, yes, a writer and a reader. The Alice/Rooney conceit will draw up a good bit of critical attention, I assume, but the epistolary element of the book, a sort of ‘track changes’ feature within the plot, is not only where the big questions of the book get bounced and tentatively answered, but where some of the most crystalline prose happens, where the characters slowly turn their attentions out to the world and not just the cultural paradigms that govern it. One of Eileen’s later emails—you’ll know it when it lifts you along—has the speed of a true runaway revelation. Those few pages alone are sublime.

And the rest?

One of Rooney’s most consistent criticisms is that, for a feminist, Marxist, and socialist, her books only feature differences of sex and class in the background. What’s up front is the stuff that translates smoothly from the unaffected, stage-direction-y prose style of big contemporary fiction (coming-of-age, romance) to a script for a Hulu original. And to be sure, no one would be off the mark in saying that “Beautiful World, Where Are You,” even in its occasionally clinical discussions of art’s social function, offers no clear diagnosis for how art can push back against consumerism and fascism.

The book’s project is in admitting to the impossibility of such grand narratives for art’s function, and how art manages to survive without them.

Then again, that’s not exactly this book’s project; in fact, the book’s project is in admitting to the impossibility of such grand narratives for art’s function, and how art manages to survive without them. If we take Alice’s premise that art is “definitionally useless,” born of and feeding into the privilege of leisure—the original Greek meaning of that word being “time spent on reflective thought and wonder,” as Eula Biss notes in “Having and Being Had”—isn’t it asking too much, or at least making the wrong demands of art to fix the world’s problems? (Some art should gesture towards solutions, sure, but precise renderings of problems can help too). Perhaps it’s the way autofiction softly blurs what’s real and what’s not that makes us ask so much of novelists other than the definitionally useless job of, well, defining things. Even Simon, who works as an advisor for a left-wing parliamentary group, admits that his office job “has absolutely nothing to do with helping people” on the ground.

Minor political consultant, famous novelist, warehouse worker, and lit mag editor; it might seem an insult to say so bluntly that they’re cut from the same wrinkled cloth of life in late capitalism, but it would be a true insult to conflate how much they earn or get recognized with what their improbable relationships are worth. The best part of “Beautiful World, Where Are You” is that it doesn’t end with some big paean to the power of unconditional love, but that it starts with that forbidden and simple desire as its premise, that small forms of care triumph throughout the book, however mealy-mouthed they may seem. This is sincerity that doesn’t make a show of being sincere, and how strange that such sincerity seems brightest when Rooney crafts a protagonist most likely to be her disheartened and distant avatar. How strange that Alice is not the Rooney that gets lauded, despised, or dismissed. How strange that an epigraph that shows Rooney making amends with being “a small, a very small writer” somehow makes the world in this book balloon to a size that captures not just the lives of a few people, but the “light radiating softly from behind the visible world” even if it cannot be held; even if it proves maybe nothing except that we all have the same blind spots.