The first time I heard Taylor Swift’s Midnights, I thought the universe was playing some kind of cosmic joke on me. Surely these weren’t the songs that I’d spent so long waiting to listen to; from an artist that I had immense admiration and respect for? Surely she was going to release another statement saying, “Sike! Here’s the real album, with music that’s actually tolerable.”

Weeks passed, and I kept waiting for the songs to grow on me. However, I just found myself getting more irritated by them. I eventually ended up having a conversation with a friend that made things crystal clear: the real reason we couldn’t bring ourselves to like Midnights is because we’re not straight, millennial, or white.

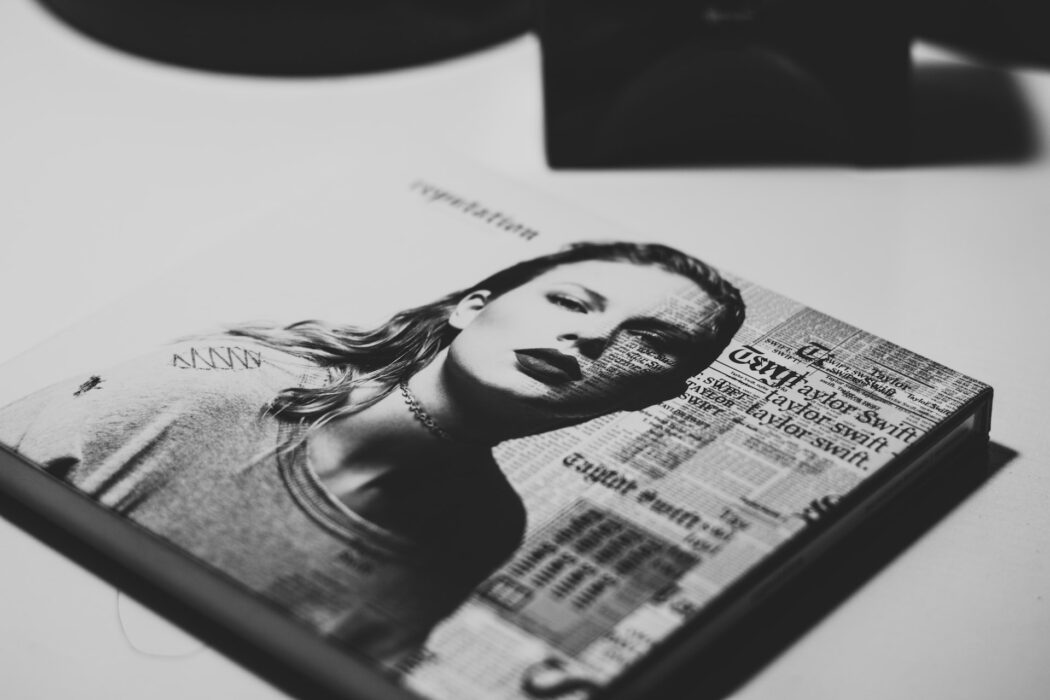

Swift’s white feminism has never been a secret. She’s benefited from connections and structures that have uplifted her from the start of her career, and yet she fails to fully acknowledge her race or class privilege. Swift presents a narrative where she can ignore intersectionality and get away with doing the bare minimum, as seen through songs like “The Man,” which glorifies white corporate culture and ‘girlboss’ feminism. Not to mention the performative allyship in “You Need To Calm Down,” with Swift hijacking queer cultures to boost her own image. Almost all of the opening artists in the upcoming Eras tour are white women who don’t need the boost her platform gives them. Even her collaborators aren’t immune from this: just remind yourself of Lana Del Rey’s infamous Instagram post.

Swift’s feminism is rooted in an individual empowerment that disregards the struggles other women in the entertainment industry go through, who are affected not only by systemic sexism, but also racism and homophobia.

This brand of feminism applauds women like Swift for being a “feminist icon” when plenty of other women have done the same, often without being granted the same privileges. Swift’s feminism is rooted in an individual empowerment that disregards the struggles other women in the entertainment industry go through, who are affected not only by systemic sexism, but also racism and homophobia. Everything is about Taylor Swift, all the time: and Midnights undoubtedly exemplifies this mindset.

“Anti-Hero,” the album’s lead single, immediately became a viral sensation upon release. Netizens praised its relatability, claiming that it was her most raw and honest work to date. Without the Swiftie-coloured glasses in front of your eyes, however, the song can be seen for what it really is: self-pitying and repetitive, with shallow lyrics crafted to perfectly fit the TikTok algorithm. The refrain of “It’s me / I’m the problem, it’s me” is a prime example of how young white women use a sort of self-aware victimisation to their benefit, wherein anyone who disagrees with them is guilt-tripped into feeling bad for them instead. To borrow the trending internet phrase, it is fueled on their ‘main character syndrome.’

We see the same kind of self-flagellation and “covert narcissism” (in Swift’s own words) in “Mastermind,” where she claims that she manipulated her partner into falling in love with her. The song spawned a whole league of mostly white and straight women on TikTok to share their own stories with the lyrics, “We were born to be a pawn / In every lover’s game” in the background.

“Vigilante Shit” echoes the same sentiments through lines like “Ladies always rise above / Ladies know what people want.” Swift idealises a white woman’s revenge fantasy, one that is only relatable to a very specific audience and leaves the rest of us unimpressed.

Without the Swiftie-coloured glasses in front of your eyes, however, the song can be seen for what it really is: self-pitying and repetitive, with shallow lyrics crafted to perfectly fit the TikTok algorithm.

This brings me to my last point: Midnights is just bad music. I’ve always admired Swift’s lyricism more than anything, but this album puts her reputation as a master storyteller under major scrutiny. Half of the songs sound like she’s fighting for her life, trying to make regular sentences rhyme into a melody that just doesn’t fit. The lyrics are tacky and meaningless, full of purple prose that sounds pretty but never goes anywhere. Experimentation is a thing of the past, and all the tracks are virtually indistinguishable from each other at first listen.

Take the first verse of “Maroon,” which abandons all sense of rhythm to make way for Swift’s attempt at humour with the line, “Your roommate’s cheap-ass screw-top rose, that’s how.” Her metaphors are ridden with cliches, to the point where they sound like they were picked right out of a fifth grader’s homework assignment: “He was sunshine / I was midnight rain”?; “My smile is like I won a contest / And to hide that would be so dishonest”? What ever happened to subtleties and complex writing?

Not to mention her blatant use of provocative imagery without any sign of critical thinking regarding its implications. Hearing a white person say the words “I can reclaim the land” is never a good sign, even if it’s in a radio pop hit. Or the line in “Snow On The Beach” that goes “Life is emotionally abusive” out of seemingly nowhere, followed by a complaint about how awful her flight was. It’s hard to take lyrics like these seriously from someone who is notorious for over-using her private jet.

More important than debating over the quality of the songs, however, is for fans of Taylor Swift to question why they feel so defensive over this album.

Despite these critiques, there are still some admittedly salvageable tracks from the trainwreck that is the rest of the album, and Swift’s ability to create catchy earworms hasn’t fully yet left her. “Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve” is one of the few songs with a consistent thematic thread running through the lyrics, rife with religious imagery and giving us heartbreaking lines like, “Give me back my girlhood, it was mine first.” “Sweet Nothing” is reminiscent of her older love songs, with breathy vocals and trademark romantic lyrics that feel like a gentle hug. I’ll even praise “Karma” – it’s fun and lighthearted in a way that calls back to Swift’s Reputation album. It’s a song that doesn’t take itself too seriously, which is what Swift does best.

More important than debating over the quality of the songs, however, is for fans of Taylor Swift to question why they feel so defensive over this album. Swift is a well-respected and admired public figure at large, and yet people continue to posit her as the underdog in her narrative. If the same structures of power that benefit Swift also benefit you, as a listener, then maybe you have some internal questioning to do about why you’ve idolised this rich, white woman to a point where hearing any form of valid criticism surrounding her art seems impossible to handle.

In the end, maybe Taylor Swift is the problem.