It’s been extensively reported in the news media. Everybody, from media commentators to industry insiders to financial analysts have been whispering it for years: traditional television is dying. As the mountain of evidence continues to grow the chorus of pessimistic voices is getting louder and louder: at a recent Comcast Corporation quarterly earnings conference call, the head of NBCUniversal, Steve Burke, assessed the situation bluntly. “I just think it’s unreasonable to assume that the ratings for [cable] are going to grow if you look over a five- or ten-year period.” For industry participants, this is a far cry from the mid-2000’s when Bay Street and Wall Street analysts were celebrating the strong growth in television network earnings.

Between the third quarters of both 2013 and 2014, the television industry lost over 2.2 million customers – a decline of nearly 4 percent, according to data from Nielsen. Even worse, top television networks nearly all suffered large year-over-year declines in viewership in the same period. Primetime ratings fell 14 percent across the NBCUniversal cable cluster, while the ratings of TNT and TBS, both owned by Time Warner, fell by 13 percent. Moreover, total advertising revenue, on which networks rely heavily, has stagnated over the past few years.

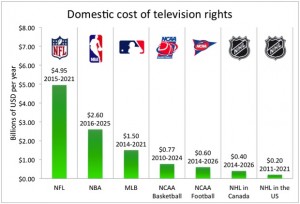

Amid the doom and gloom, the largest television networks are responding by shifting their focus to areas where they have a competitive advantage over other channels of distribution (read Netflix). In particular, there has been a surge in network interest in live sports programming. Case in point: the big four North American sports leagues – the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL – have all recently signed new broadcast deals worth significantly more than previous agreements. The NHL deal with Rogers Communications, worth CAD$5.2 billion, is one of the largest media rights deals in Canadian history. MLB’s broadcast deals with Fox, TBS, and ESPN together represent a 100 percent increase in broadcast rights fees over the previous agreement. Even more impressive is the NBA broadcast deal, announced last fall, which will nearly triple the league’s annual television revenues come 2016.

Deloitte estimates that the total value of global premium sports rights (i.e. the rights fees for the most popular sports leagues) will be USD$28 billion in 2015, a 12 percent increase on 2014. Given the boom in sports broadcasting rights, many commentators are questioning whether there is currently a sports rights “bubble”, and if so, when it will burst.

Even amidst the fall in overall viewership, sports programming continues to attract large television audiences, with strong growth rates to boost. In an era where online video streaming has enjoyed considerable success at the expense of network television, the thrill and excitement of live sports has simply proven irreplaceable. 114 million U.S. viewers watched this year’s Super Bowl on television, shattering the record for the largest audience for a U.S. television program. In fact, this was the fourth time in five years that the Super Bowl has set a new viewership record.

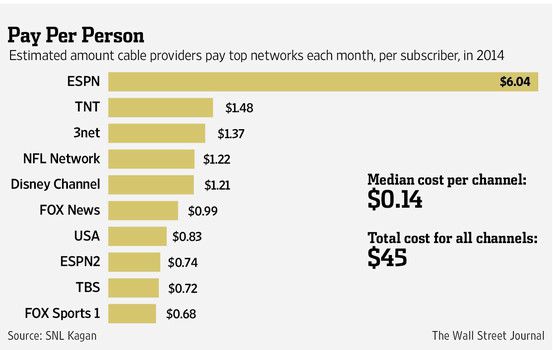

With the mass appeal of sporting events and the significant attachment consumers place on professional teams, it’s easy to see why the sports broadcasting market is a captive market. Thus, television networks that lock up the right to broadcast games over the long term are in a strong bargaining position when the time comes to negotiate distribution fees with cable service providers. The best example of this is the Disney-owned ESPN network: estimates peg the amount that cable providers pay ESPN each month at USD $6.04 per subscriber. Meanwhile, the median price cable providers pay per channel amounts to around just USD $0.14 per subscriber according to research by SNL Kagan. Moreover, even as advertising dollars get scarcer for the television industry, live sports programming continues to be a magnet for advertisers. Together, these factors have led broadcasters to increasingly view live sports as a premium asset.

However, this has not done much to quiet the commentators who think that there is currently a sports rights “bubble.” These critics point to the squeeze in profit margins at networks such as ESPN due to the recent broadcasting deals. In the quarter ending Dec. 27, 2014 (Q1 ’15), Disney’s operating income from its ESPN division declined 2 percent year-over-year. Disney’s chief financial officer, James A. Rasulo, told analysts that the decline was due to rising sports costs, adding that ESPN would see higher costs again in the second quarter.

Moreover, deals such as the NASCAR broadcasting deal announced in mid-2013 lends greater credibility to the notion that the global wave of money flowing into broadcasting rights might be overdone. Even though NASCAR television ratings plummeted by 47 percent since NASCAR negotiated its previous TV deal in 2005, NASCAR was able to land a new deal in which its rights fees increased by 46 percent, from USD$560 million per year to USD$820 million per year. The deal, which primarily involved two emerging sports networks (Fox Sports 1 and NBC Sports Network) bidding for the contract, comes against the backdrop of increasing competition for live sports programming among broadcasters.

However, given the length of these contracts and the cyclicality of distribution fee negotiations, it appears as if only time will tell if the spate of recent deals were prudent investments.