In a field as subjective as cinema, there are bound to be misinterpretations of films, and in an era as plugged-in as ours, those misinterpretations are bound to spread. It’s happened before with notorious films like Fight Club—a satire that was taken too literally by the very people it was trying to critique. In a similar fashion, many films over the past few years have given way to a new pseudo-genre, dubbed the “‘good for her’ cinematic universe” on Twitter and other social media platforms. The category, consisting of fan favourites such as Knives Out, Gone Girl, and Midsommar, earned its name due to the similar plotlines of the films: female protagonists who undergo some sort of harrowing or transformative experience and come out on top. But someone who has seen most of the films in the original “good for her” tweet would know that some of those protagonists are not like the others. While it is cathartic and needless to say, fun, to see a female protagonist displaying strength and overcoming what are often inherently patriarchal obstacles, it’s also worth paying attention to the actual elements within the narratives that indicate how some of these women may not be as deserving of the congratulatory title.

She’s evidently not a character you’re meant to root for, and yet so many do, burying the point of the movie under an avalanche of misplaced female empowerment.

An example is Midsommar, which follows Dani, a woman who travels with her boyfriend and his friends to Sweden following a tragic event in her family. The group spends time with a commune as they celebrate a traditional summer festival. The film quickly turns into psychological horror as the community is revealed to be a white supremacist cult. Throughout the film, Dani’s relationship with her boyfriend is depicted as incredibly unhealthy—he’s very emotionally manipulative, something that becomes important in Dani’s own journey. Being trapped in that relationship and dealing with the aftermath of tragedy puts Dani in a vulnerable emotional state that allows her to be manipulated by the cult. They manage to successfully distance her from everyone she loves and make her feel as though she will only ever feel loved and accepted within this cult. When presented with this narrative, it’s evident that Dani subconsciously traded one figurative prison for another, leaving her arguably worse-off than she was at the beginning of the story. There is nothing “good” or liberating about the final shots of the film, as Dani watches a murder she orchestrated with a harrowing smile on her face, indicating to the audience that she has fully lost herself to the cult.

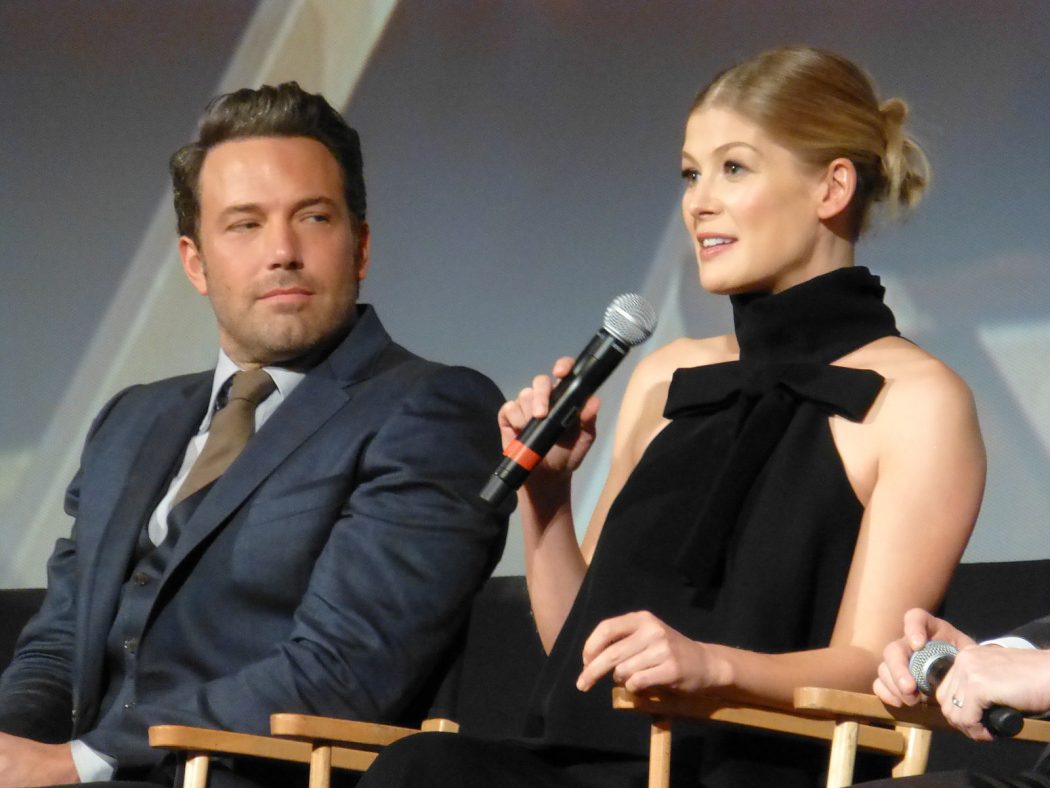

Another poster child for the genre is Gone Girl, a film with many layers worthy of analysis. It follows Nick Dunne as he becomes the primary suspect in his wife’s disappearance and potential death. As it turns out, Amy is very much alive and has plotted an elaborate revenge scheme in an attempt to make Nick suffer, to reclaim her identity, and most likely, to amuse herself. Even though Amy details the things that led her to her predicament (including parental pressure and her unhealthy relationship with Nick), the film, and the novel it’s adapted from, depict her for who she is—a vindictive psychopath. She falsely accuses multiple people, lies, steals, and even commits murder—things that further cement her role as the villain and antagonist of the story. What’s more, Amy comes from a place of both racial and socioeconomic privilege. Not only does she know this, but she uses her race and class to her advantage in order to get away with her meticulously plotted crimes. She’s evidently not a character you’re meant to root for, and yet so many do, burying the point of the movie under an avalanche of misplaced female empowerment. The ending is not a celebratory occasion, but rather a gutting and shocking portrayal of what happens when two terrible people push each other too far.

A female character in a prominent role doesn’t automatically mean that she’s absolved of all her transgressions, or that the film demands respect for that character.

This is not to say that every movie anointed as “good for her” cinema is undeserving of the title, or that the term should be dismantled as a whole. In fact, most of them are deserving. Take Knives Out, which depicts a woman of colour besting the privileged white family that mistreats and takes advantage of her in numerous ways, or Ready or Not, in which the protagonist escapes her husband’s murderous family. The films in this genre that warrant respect and admiration for their protagonists are those in which the heroine overcomes various challenges and ends the film with a newfound state of autonomy and reclaimed fortitude. This doesn’t happen in either Midsommar or Gone Girl, as we see the protagonists come full circle and end up in either the same or worse place than they were at the start of the film. These characters call for sympathy at most, but certainly not respect or praise.

Yes, Amy Dunne’s “cool girl” monologue is one of the most memorable moments in recent cinematic history, but as with all media, it’s important to retain a critical gaze. A female character in a prominent role doesn’t automatically mean that she’s absolved of all her transgressions, or that the film demands respect for that character. After all, female characters can be just as layered, flawed, and downright evil as male characters.