The curation of taste is not new in arts and culture. Taste, almost by definition, extends past the individual and forms communities through commonality. The interests that these tastes reflect have correspondingly been popularized, ghettoized, and streamlined into easily recognizable genres and subcategories. In the contemporary context of Netflix, Spotify, and algorithms that are fine-tuned to predict what will/ought to be popular, one could argue that entirely personal taste has now become a romantic illusion reminiscent of a simpler time. Conversely, it can be said that these algorithms are simply a natural continuation of trends we’ve had in our lives ever since William the Conqueror hyped up his court minstrels’ first EP. Before embroiling ourselves in arguments that will come across either as Elon Musk-style revisionism or “throw your Samsung TV off a cliff they are watching you”-style paranoia, let us venture into asking and optimally answering certain questions. First, what does it mean to have good taste? Second, how, if at all, does technology affect taste? If so, does this have any lasting effects on individual taste and its place in our social lives?

Art and life are subjective. Not everybody’s gonna dig what I dig, but I reserve the right to dig it

The conversation surrounding taste is expansive and lacks any form of descending consensus. We all have that one friend who knew that band before they became popular, the one that watches movies with subtitles, and the one whose house is decorated like an Ikea catalogue. Whether we choose to admire or despise such people, we can all agree that each individual has a sense of taste, and yet separate from the individual, no one can quite agree on what taste looks like. The Oxford English Dictionary defines taste as “good or discerning judgement, especially with regard to what is aesthetically pleasing, fashionable, polite, or socially appropriate.” Oscar Wilde once wrote “I have the simplest tastes. I am always satisfied with the best,” while Whoopi Goldberg simply put it: “Art and life are subjective. Not everybody’s gonna dig what I dig, but I reserve the right to dig it.” Regardless of whether you find Wilde, Goldberg or the Oxford English Dictionary a more credible source of information (these names were placed in order of who we personally find to be the most authoritative), all of these agents point to some defining features of taste that make it so hard to pin down: subjectivity, relation to sociability, and the assessment of quality.

The subjectivity and the sociability of taste inherently leads to the mass variation of communities that exist within the arts. If taste wasn’t social, communities would not be formed, and if it was in any way objective, the range and eclectic nature of these communities would not make any sense. Despite this subjectivity, these communities have functioned with internal actors who have placed a hierarchy on personal taste, ranging from good to bad, to Nickelback , to the duet Avril Lavigne and Chad Kroeger made during their brief marriage (RIP Love), all the way down to rock bottom. Determinants of formal taste for the longest time were vertical, meaning that authority was vested in certain key actors (critics, cultural elites, publishing houses, record companies etc.) to assess the quality of any given artistic venture. The exponential growth of the Internet and its various media platforms has given rise to a more horizontal approach to quality assessment. When the hierarchy of taste is pushed onto its side, anyone can give their two cents on the latest movie, album, or exhibit. Now, the “professional” voices that once determined good taste are placed in a democratic forum where anything can be critiqued, questioned, and considered.

Regardless of whether it is understood as vertical or horizontal, taste has always been influenced (although not entirely dictated) by the presence of a third actor, whether it be the professional critique or the majority voice found through online chatter. Algorithms hold an interesting position in this dynamic because they are a synthesis of both the professional critique that benefits from a wealth of information and the horizontally democratic structure that is centred on the consumer.

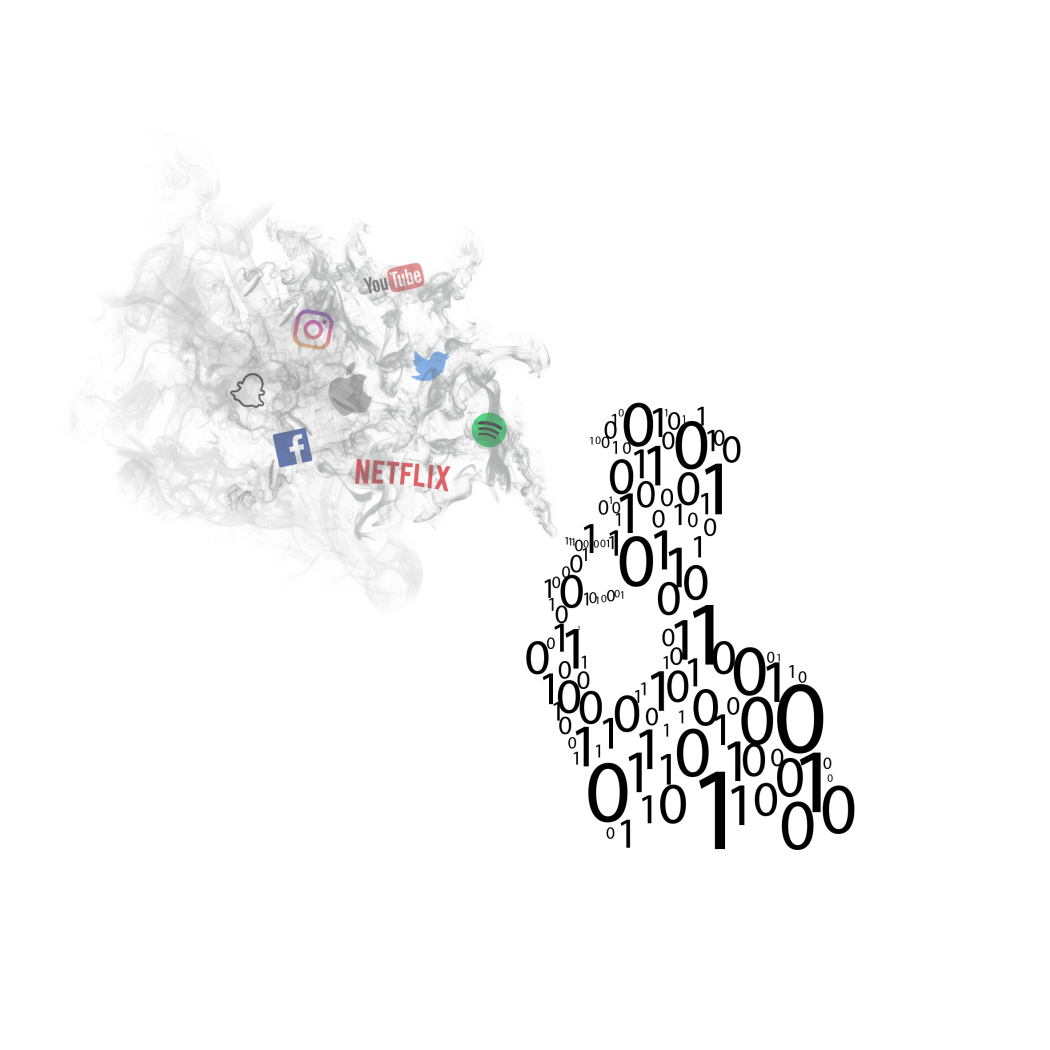

Here is a brief introduction to this new third-party participant: recommendation algorithms, from Spotify or Netflic, currently direct millions of streamers towards new content using an ocean of data, often placing media in the hands of consumers that they might not have otherwise discovered. These algorithms generate their suggestions based not only on one’s preferences and recent listening history, but also using a method called “collaborative filtering” where they compare any given individual to similar users – a classic case of “people who like A also like B.” Spotify, in particular, also codes each individual song into comparable ones and zeros in order to get over the “cold start problem” – when there is no data about a recently released product or track – to recommend those obscure songs without many plays. Advertisers track your browser history using cookies to send you a targeted footwear ad after you scroll through a Buzzfeed article entitled “25 Stylish Pairs of Fall Booties For Less!” This reminds you not only that Buzzfeed is a sad place where your productivity goes to die, but also that your activity online is constantly interpreted, encoded, and then targeted.

Algorithms have the enhanced ability to streamline a bottomless banquet of media into digestible portions, but do so in a way that affirms pre-existing biases that one may already have

The main issue presented by such algorithms is that they are personalized, but not personal. Taste is deeply connected to the arts, and there is something inherently un-analytical and unprogrammable about what touches an individual and what one identifies with. Algorithms can also fatally miss the nuance of our preferences and can falsely assume many common denominators that tie together our assumed preferences. Netflix often makes these leaps, offering suggestions such as “because you watched Knocked Up you will LOVE The Revenant” (this is a true example). It all comes down to predicting human preferences and behaviours, but it’s being done by lines of code sifting through data, a less than perfect process.

Algorithms have the enhanced ability to streamline a bottomless banquet of media into digestible portions, but do so in a way that affirms pre-existing biases that one may already have. Seeking out affirmation to strengthen one’s preferences is not new or individual to the technology of streaming services, but by God, is it done faster and with more accuracy. The technology used in streaming servers cannot create individual taste; they can only make assumptions and predictions on pre-existing preferences encoded in data. It takes the introduction of human agency to accept these predictions, and make them real.

The cautionary tale of advanced technology in arts and culture is that sometimes, to make something easier is not always worthwhile

We live in a time where we can still trust that cool and slightly manic friend who stays up all night going into the depths of Soundcloud, or appreciate recommendations from that other friend who, for reasons we don’t want to get into, has watched every single movie under Netflix’s “Thriller” section. Algorithms as a third-party agent in the curation of taste are revolutionary in the way they facilitate the access, digestion, and acceptance of media, but when seen for exactly what they are, will not end individual taste as we know it. The cautionary tale of advanced technology in arts and culture is that sometimes, making something easier is not always worthwhile. To only enjoy the options that are presented is to create an individual echo chamber, something highly self-affirming, but ultimately limiting.

The use of technology in the curation of taste only has something to add to our experience of art, and yet it risks replacing some of the dialogue and debate that characterizes culture if we allow it to do so. Algorithms are a natural continuation of how we have engaged with taste formation, but like any innovation, they deserve a debate and conversation equal to what lies at the foundation of every artistic community and individual preference. In short, don’t throw out your Samsung TV (it is watching you, but ultimately you aren’t that interesting), but also don’t copy and paste Spotify’s weekly feature list into your journal under the title “Songs that Define my Essence.” Although it is complex and decisive answers are scarce, it is important to recognize and work to reconcile the tension that exists between robotic algorithms (and all the baggage that comes with them, such as corporate profits and privacy infringements and the “datafication” of society) with what ultimately makes us human – our ability to unanimously hate Nickelback under the guise of subjective taste.