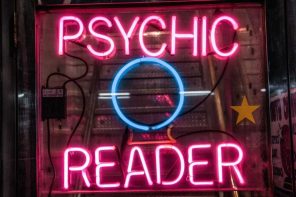

Ever since the “Heavenly Bodies” Met Gala theme of 2018, we have been seeing a resurgence of Catholic influence on fashion. At the event, celebrities donned diamond encrusted crucifixes, golden halos, and even angel wings. This high fashion work is in turn inspiring the style of fashion enthusiasts all over the world, to the point where Shein now sells rosaries and “Virgin Mary Jewelry.” As the “Catholic Girl” aesthetic has made its way to mainstream culture it begs the question: is religion becoming an aesthetic?

As a (loosely) Christian individual, I have only begun to notice this trend because the people around me have started to wear Catholic icons; however, upon further research, this has been occurring with various religions. For example, the evil eye is part of Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic traditions, and is used for spiritual protection from wicked beings in many of these cultures, yet people mainly in the West have adopted the evil eye simply for its “mystical aesthetic.” Thus, the meaning has been diluted by those who cannot appreciate the sign for what it is. Dreamcatchers have also gained and lost popularity over time. These objects are traditionally hand made and hung on cradles for protection over children by First Nation groups, yet the West has taken to making earrings and decorations out of them, watering down the meaning of the symbol.

The idea of a Catholic Girl aesthetic is speaking to a much larger problem of religious appropriation, which has become the basis of the spirituality industry in western countries.

The idea of a Catholic Girl aesthetic is speaking to a much larger problem of religious appropriation, which has become the basis of the spirituality industry in western countries. This form of capitalism is the source of many forms of religious appropriation since the “spirituality” that has been marketed to the West is an amalgamation of ancient, legitimate religions from other countries. In commercial “spirituality” stores in the United States or Canada, one can typically find Hindu statues of Vishnu and Shiva, Buddhist Mala beads, or objects with Hamsa designs originally meant for protection in Islam and Judaism. All are marketed as generic keepsakes meant to bring good luck or protection. We are taking religious and spiritual icons from all over the world and stripping them of their history and meaning by making them more palatable to a predominantly white, Western population.

Thus, when influencers take these items of worship and place them at the center of microtrends like the mystical evil eye aesthetic or the Catholic Girl aesthetic, we are reducing the meaning of the objects and icons central to spirituality in the rest of the world. The items are then reproduced for cheap and sold to millions at a time, further devaluing the once handmade rosary beads or hamsas. Spirituality is defined as caring for the soul and not the material aspects of life; however, our brand of Western spirituality has clearly been infiltrated by capitalistic greed, considering how companies can now take from various cultures and promise inner peace or good luck.

Spirituality is defined as caring for the soul and not the material aspects of life; however, our brand of Western spirituality has clearly been infiltrated by capitalistic greed

Nevertheless, many healthy ideas and practices have come from other cultures in addition to physical items, and we have benefited greatly from these principles as a society. For example, the practice of yoga comes from Hinduism, and although it has definitely been altered and remade into a very Westernized version of itself, yoga has maintained the original Hindu goal of connecting with the soul of the universe, significantly improving lives all over the world. Despite the rapid rise of the yoga industry, the fact that it is still being practiced today without the promise of a certain aesthetic proves that we can draw from other cultures without simply appropriating. We just require the proper respect and appreciation for the practice we hope to adopt.

There is a point where the line becomes blurred. If the practice is respected and the original goal is maintained, does this count as religious appropriation? Does the commercialization of something by another culture count? There are no real answers to these questions; however, if we collectively choose to understand what we buy before we buy it and respect the beliefs we do not understand, we can move between cultures and grow from these experiences without degrading them.