On September 15, I attended a “Fireside Chat” on queer and feminist science-fiction with Hugo-award winning author Becky Chambers. Her most recent novella, A Prayer for the Crown-Shy—the conclusion of her Monk & Robot series—was released in July.

This free online event was part of the series “Disrupting Disruptions” hosted by McGill’s Dr. Alex Ketchum; the series promises to discuss the relationships between feminism and digital technologies, including how feminism takes shape in speculative fiction. As stated on the series’ Facebook page, the goal of these talks is to bring “scholars, creators, and industry” together to discuss how feminism and social justice take shape in the worlds of technology and publishing.

The atmosphere was very relaxed and friendly, with Chambers and the hosts talking casually and joking with each other. There was plenty of time for audience questions, and while audience members were not allowed to turn on their cameras, they could type as many questions or comments as they wanted. Although it is impossible to capture the full richness of the conversation, I wanted to share some of the main topics discussed.

Science Fiction, Solarpunk, and Hopepunk

. . . a kind of science fiction which thematically emphasizes growth, and a certain level of optimism about the future.

Chambers writes a mix of science-fiction and fantasy, and many of her stories arguably take place in post-apocalypse settings. However, she deliberately avoids making her stories dark. Rather than give in to dystopia, Chambers wishes to offer her readers a different option, and embraces hope.

“The after is what interests me,” Chambers said. “Most of my work like Wayfarers or Monk and Robot takes place after a struggle has happened. I have to try and make the case: the struggle [for liberation] was worth it, now here’s what we get in the aftermath.”]

However, as Chambers notes, no world is perfect: “An important part of my stories is that there is no one size fits all solution. We will always have to fight and change and consider the imperfections of the society we build—who has fallen through the cracks and margins, and improve it as much as we can. It can get better, I do believe that, but only if we know what sort of better it is we are imagining.”

Chambers’ community-focused approach reminds me of hopepunk and solarpunk. Stories in these sub-genres often explore hope, community building, and reconnecting with the environment. They are a kind of science fiction which thematically emphasizes growth, and a certain level of optimism about the future.

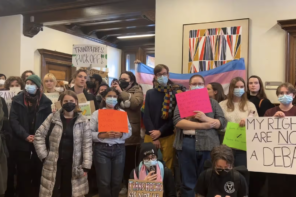

For Chambers, diversity is also an important part of the future, although she does not consciously work to make stories diverse. In her own words: “As a queer writer, I don’t know how I would write anything else. [In these stories] I am writing about myself and the people I know and love. I am writing my family. This is not some checklist or secret agenda I’m pushing. I am simply writing the world as I know it—an honest depiction of the world. We’re queer, we’re here, and we’ve always been here.”

Transforming the Darkness

During the chat, Mathieu Lauzon-Dicso—owner of Saga, a local bookstore that partnered with McGill for this event—asked a wonderful question: “How do you transform the darkness, the toughness, the hollowness in your stories, into light? Something that feels comfortable and beautiful? It seems like we reach the good from the bad, so these are not separate things. But how do they evolve one into the other?”

The answer, according to Chambers, lies in hope. “Hope can only exist in the face of challenges and fears. To say that when bad things happen, all good stops, is nihilistic. Hope is how we heal. We always move on from tragedy, even if we can never fully let it go. That’s why I always include some darkness in my work on the page: I find it important to sit with difficult moments where something unfair, frightening, shocking happens. However, I use them sparingly because that is how it happens in life.”

Chamber’s personal perspective also strongly influences her work. “The more scared and angry I am in the real world, the more gently I write. I am writing the things that I need to be told. Because I know that if I feel that way, other people are scared, and are feeling that way too. My experience is not unique, so if I can think of what I would want somebody else to say to me, that is what I want to try and write for others. But it also comes from a place of defiance. I find that in the moments when I start to feel hopeless, that nothing can be done, those are the moments I really dig my heels in and get going to write something beautiful. It’s the only way I know how to face the things that scare me, and I’m not sure what I would do without it.”

The desire for comfort in hard times is practically universal, but it takes real skill to be able to take that fear and pain and channel it into kindness.

This answer resonated with me so much that I wanted to transcribe it in its entirety. Beautiful works of fiction have made a world of difference when I am scared or suffering; that is part of why I love reviewing books. The desire for comfort in hard times is practically universal, but it takes real skill to be able to take that fear and pain and channel it into kindness. I really admire Chambers’ dedication to her craft, and the ethical principles that guide her writing and stories are truly a soft landing in these hard times.

Recommendations

I am always curious about what an author reads, as I find that these book recommendations say a lot about them and their work. Here are a few of Chambers’ most recent reads, as she described them:

Light from Uncommon Stars by Ryka Aoki is an amazing genre-bending science-fiction and fantasy story, “off the wall imaginative,” with some wonderful queer characters. Although the book deals with some heavy topics, it is worth the read for Chambers.

Elder Race by Adrian Tschaikovsky is a novel which follows an anthropologist on a strange planet, and really gets into the sociology of science-fiction. While Chambers endeavours to explore both social and hard sciences in her writing, she laments that not enough contemporary authors dive deep into sociology.

Finally, Spear by Nicola Griffin is a feminist, queer retelling of Arthurian myth. Chambers describes Spear as “one of those books that was so good I almost got angry at.”

In terms of non-fiction, Chambers recommends How to do Nothing by Jenny O’Dell. According to Chambers, this book has been essential to “challenging the late-stage capitalist trap we are all in,” and offers excellent tips for how to stop, think, rest, and re-contextualize the events of our daily lives.

Unfortunately, I was not able to cover everything that Chambers discussed in this article. Luckily, a full recording of the talk can be found on their Youtube channel. If you are interested in learning more, or in attending the other events in the series, feel free to check out their website.