While browsing McGill’s approved freshman courses, there was one that immediately caught my attention: Introduction to Deductive Logic, or PHIL 210. Finally, after years of poring over Clue and TED-Ed riddles, here was the perfect opportunity to develop one of my longtime interests. Sure, the course description may have gone over my head, Reddit may have disparaged its exam, and my best marks may have been in the opposite “sort” of classes. Despite these deterrents, I reasoned that formally studying logic would be beneficial to any future career. If my GPA had to take a slight hit along the way, so be it.

By the second week of the semester, these initial worries lay forgotten—the content was coming so easily to me! With every proof I constructed and every concept I grasped, the ensuing surges of dopamine inflated my ego. I felt like a hacker assimilating scores of raw data, or maybe an explorer charting foreign terrain. I was a natural! I got it. As you may have predicted, however, this rudimentary sense of mastery was a far cry from actual expertise. Just a month later, I would often hole myself up at McLennan, laptop glowing and pages flying as I strained to piece together what the professor said in lecture.

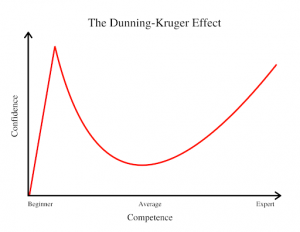

I had succumbed to the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias first substantiated by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger. Essentially, their 1999 study evaluated participants on grammar, logic, and humour before asking each to rate their own performance. Expanding upon previous work on overconfidence, Dunning and Kruger identified an intriguing pattern among the participants. Consistently, those performing in the lowest quartile greatly overrated their performances as “above average,” while those in the highest quartile tended to underrate theirs.

To explain these misjudgments of competence, Dunning and Kruger pointed to the very levels of competence being judged. Because the higher performers were better versed in the tested areas, they were more cognizant of how much they had yet to learn and thus minimized their skills. On the other hand, those who performed poorly did so because they were inexperienced, resulting in common beginner mistakes. Then, because these participants were also unable to recognize these errors, they believed themselves to have produced much better results than they actually did.

The incompetent are blind to elementary errors; the competent are conscious of imperfections where there may seem none. It’s a simple enough concept—beginner and expert, the two ends of the learning curve. Beyond this generalization, though, is an even more compelling message: to be incompetent is to hold the potential for becoming competent, and to be competent is to have previously been incompetent when one first begun. What’s important for anyone and for any pursuit is just that—to become competent one must first begin and then continue on.

Heralded by our individualistic values and self-serving norms, we are taught that competence is what separates us from the masses…

In our competitive, achievement-oriented society, unfortunately, the dread of incompetence dissuades many from approaching the learning curve at all. Heralded by our individualistic values and self-serving norms, we are taught that competence is what separates us from the masses, facilitates career success, and equates to a fulfilled life. Incompetence, by contrast, is linked with deficiency and even failure. We look down on the incompetent while simultaneously striving to distance ourselves from this label. Even in the titles of Youtube videos on the Dunning-Kruger effect (e.g., “Why incompetent people think they’re amazing” and “Why Dummies Think They’re Smart”), there’s a clear separation between “us” (the competent) and “them” (the incompetent).

Indeed, the “oblivious beginner” is not a permanent state weathered by an unfortunate minority, but a universal experience that we must all endure.

The problem with this frame of thinking is that we are all incompetent in some area or another. Indeed, the “oblivious beginner” is not a permanent state weathered by an unfortunate minority, but a universal experience that we must all endure. As such, we should not view the Dunning-Kruger effect as an explanation for the world’s “stupid people,” but as a natural part of learning. This carries over to our present reality as university students, a time during which we are meant to explore our interests and develop ourselves as individuals. With introductory classes in particular, the Dunning-Kruger effect can truly be an instigator to academic experimentation and growth.

As described at the beginning of this article, I was swept away by the exciting, ego-stoking rush of beginning PHIL 210. Though it may be embarrassing to look back at this unfound self-assuredness, I may have quit by midterms if immersion in new subjects brought crippling doubt instead of inspiring élan. In this way, the Dunning-Kruger effect paired with an introductory course is like a free-trial of how gratifying a specific subject can be. This honeymoon period curbs what would otherwise be a demoralizing experience, transforming introductory courses into exciting adventures and incentivizing students to persist with the subject.

The hard part is overcoming the fall that comes afterwards. With PHIL 210, encountering more complex topics made me realize the fundamental simplicity of ideas I had been so proud to have understood. Though previously unaware of my own ignorance, the mirage of immediate expertise faded, leaving me with an understanding of how very low I was (and still am) on the stairway of mastering deductive logic. Ignorance is indeed bliss. The less you know, the more you don’t know that you don’t know; the more you know, the more you know that you don’t know.

Persevere with a subject and the reward mounts with the workload.

When you start to realize how much you don’t know, the question then becomes whether you should abandon the subject or accept the struggle necessary to delve deeper. While the “right” decision varies by subject and by person, one ought to seriously consider even the faintest desire to continue. Persevere with a subject and the reward mounts with the workload. After all, the most proficient people are not the ones who immediately proclaimed themselves masters, but the ones who were willing to push through when others trickled out. How can anyone improve themselves if they believe that they have nothing more to learn? The faster one recognizes their shortfalls, the faster they can work to fill these gaps.

Whether it be in academics, sports, music, or any other activity, you likely have a longtime interest that remains unexplored to this day. Maybe you’ve been daunted by its scope, gotten distracted by other matters, or been overwhelmed as to where to start. Whatever this interest may be, I urge you to set aside some time for its pursuit. Sit down, do some research on introductory courses or popular beginner resources, and begin. Take this as a sign. And remember, do not fear the inevitable highs and lows of the learning curve. Embrace the Dunning-Kruger effect and you’ll emerge stronger for it.