Following the Clues and Understanding Christie’s Success

The opening page finds him standing on a platform at Aleppo, ready to board the Taurus express en route to Istanbul. Just before departing, the distinguished Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot, casually converses with the guard about his vacation plans for the next few days. Once in Istanbul, however, his plans will change, as he is called to London on pressing business and finds himself booked in on the crowded Calais coach of the Orient Express. On the second morning of the journey by train across Europe, a wealthy American is found in his room stabbed in the chest twelve times. With this discovery, Hercule Poirot and his “little grey cells” are once again called upon to solve another seemingly impossible case.

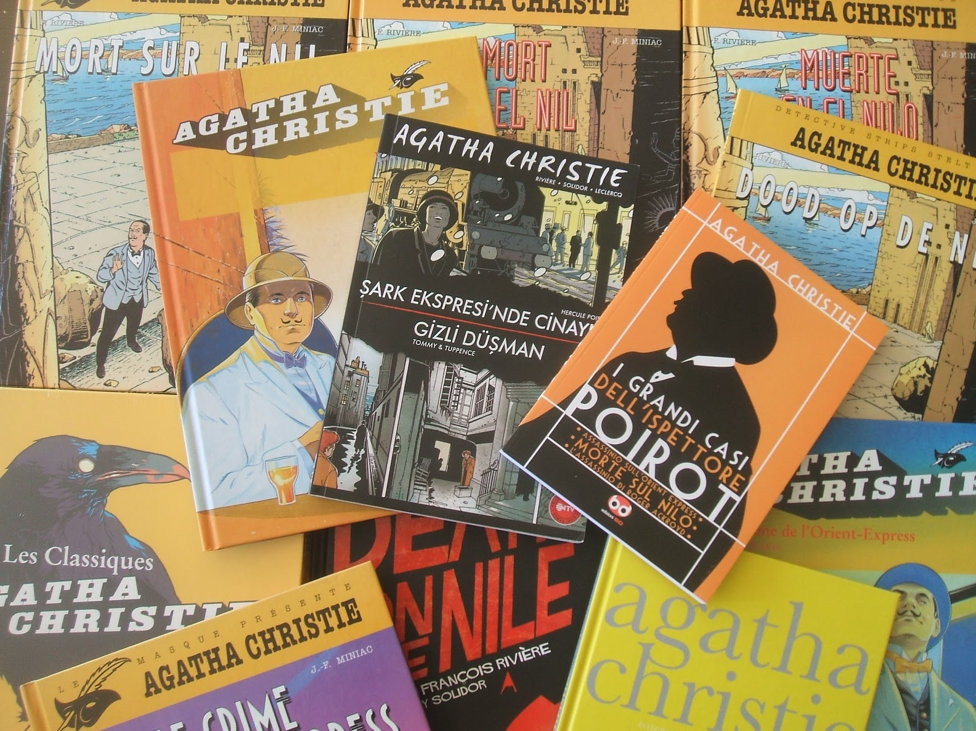

Murder on the Orient Express, first published in 1934, is the eighth of more than thirty Hercule Poirot mystery novels written by Dame Agatha Christie. The book was first interpreted on screen by Sidney Lumet in 1974 and starred Albert Finney as Hercule Poirot. Since then, it has been adapted twice for television, the most recent version appearing in 2010, with the much-beloved David Suchet playing the detective. Now, Kenneth Branagh has tried his hand at the game by directing and starring in his own interpretation of Christie’s novel. Branagh, who plays Poirot, is joined by an all-star cast with the likes of Dame Judi Dench, Johnny Depp, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Olivia Coleman playing the passengers aboard the Orient Express. The film premiered in Montreal theatres on Thursday, November 9.

Her works have been translated into more than 100 languages, making her the most translated author in the world, and estimated sales of her books are between two and four billion, coming third behind only the Bible and the works of Shakespeare.

The popularity of this novel is by no means Mrs. Christie’s only claim to fame. The author knew tremendous success both before and after her death. Beginning her writing career in her late twenties, Christie would go on to publish more than 80 books, 17 plays, (including The Mousetrap, the longest running play in British stage history) and nine volumes of short stories. Her works have been translated into more than 100 languages, making her the most translated author in the world, and estimated sales of her books are between two and four billion, coming third behind only the Bible and the works of Shakespeare.

Her success, though undeniable, does need some explaining. Even as her works were avidly consumed by millions of readers across the globe, she was being harshly critiqued by several high profile literary figures of her time. Edmund Wilson and Colin Watson were only two of her most scathing critics, the former asserting that “her writing is of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read” in an essay entitled “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?” Certainly there was a current in literary dialogue of the time that dismissed detective fiction as a low form of entertainment having “nothing to do with art”, as W.H. Auden, a self-professed Christie fan, wrote in 1948. The Christie novels were accused of an unremarkable writing style and characters which lacked depth, presenting themselves as little more than stereotypes. Murder on the Orient Express would very possibly be found guilty as charged; the proud and aloof English butler, the aristocratic Bulgarian couple, the slightly pathetic American woman who witters endlessly on, all figure in the cast which makes up Poirot’s fellow travellers.

So, what is it about the eccentric genius with the well-groomed mustache and equally well-groomed ego that has charmed billions of readers?

So, what is it about the eccentric genius with the well-groomed mustache and equally well-groomed ego that has charmed billions of readers? Some have suggested that we read Poirot, and other Christie detective stories, for the murders themselves. We do not turn to the “Queen of crime” for character development or authenticity, but for the development of the case. The clues are laid out for the reader, just as they are for Poirot, and we seek to follow them to a reasonable conclusion. Christie, who ushered in the Golden Age of crime fiction, was rigorous in this way. She steadfastly presents us with all the evidence we need to solve the crime before her detective does. The dainty handkerchief embroidered with the letter “H”, the pipe cleaner on the floor, the broken watch, all found on the floor of the dead man’s room on the Calais coach, are discovered by the reader as Poirot finds them. Christie challenges the reader: Solve the crime before he does.

Undoubtedly, the mental puzzle that we are called to solve is part of the thrill. The idea that human logic and perception can unearth the truth and thus, restore order to the universe is deeply attractive. Indeed, the journalist Anthony Lejeune comments, “The Great Detectives were – and, in Mrs. Christie’s hands, thank goodness, still are – engaged on a great business. They move, untouched, incorruptible, undefeated, among the mysteries of life and death, teaching us in a parable that there is a reason for everything, that puzzles were made to be solved, that what seems like chaos may be only the observed effects of unknown causes…” So while a man may be mercilessly murdered during the night, justice is rendered and peace regained by the work of the tireless detective who seeks to answer the “why?”

Once the murder occurs, all are suspects and tension rises as everyone but the perpetrator asks themselves, ‘what evil lurks beneath the surface?’ and ‘can I trust the person who sits next to me and civilly sips their martini?’

But, could there possibly be another cause behind the Christie craze? The closed-room technique that Agatha Christie is famous for, where all potential suspects are found together in one place, introduces a dynamic between characters rife with philosophical undertones. The murderer interacts as normal with the other residents of the English manor house, the holiday lodge in the Alps, or the Calais coach on the Orient Express. Once the murder occurs, all are suspects and tension rises as everyone but the perpetrator asks themselves, “What evil lurks beneath the surface?” and “Can I trust the person who sits next to me and civilly sips their martini?” These questions speak to the natural fear and anxiety we experience when faced with another.

This dynamic is perhaps introduced to a stronger degree in Murder on the Orient Express. As Mr. Bouc, the director of the train line, remarks to Poirot before the peace is shattered, “…it lends itself to romance, my friend. All around us are people, of all classes, of all nationalities, of all ages. For three days these people, these strangers to one another, are brought together”. The concept of strangers thrown together by coincidence or design and united in the face of tragedy is one, I think, that strikes a chord with modern sensibilities. And Branagh’s film capitalizes on this. His reimagining of Christie’s world and characters is thicker with dramatic flair and puts less emphasis on the process of solving the crime, while exaggerating the dynamic between the personalities involved. Some of the passengers are given pasts and character traits that differ from the originals in an effort to further emphasize how striking it is for such a varied group of people to be gathered in one place. The Italian car salesman of the novel, Mr. Foscarelli, is, in the film, Mr. Marquez and of Mexican background. Similarly, the Swedish missionary, Ms. Ohlsson, is replaced by the Spanish Ms. Estravados. Colonel Arbuthnot is represented in Branagh’s adaptation as a Black doctor and not a White colonel. These changes make the cast of characters more recognizable and relatable to the 21st century viewer.

While Branagh may have overplayed his part of the Belgian detective as an actor and placed too much emphasis on eliciting emotion out of his audience as a director, the film still raises the questions concerning innocence and guilt, and the appearance of good and evil that are present in the novels. Christie’s stories may be regarded as quaint and unsubstantial, but Mr. Poirot —and his method of patient, careful prodding — steadily unravels superficial appearances and reveals certain truths about what it is that joins us as human beings as well as the evil and fears that can separate us. So, in reply to Mr. Edmund Wilson, I say that far from being banal, Dame Christie’s little novels provide us with clues regarding the mysteries of good, evil, guilt and innocence that may not crack the case, but certainly set us on the right track.