If COVID-19 had left both Hollywood and Montreal untouched, then McGill students would be watching David Fincher’s newest, Mank, in movie theatres and arguing about it at Oscar viewing parties. But theatres are closed, parties are illegal, and the red carpet, star-studded extravaganza that is the Oscars has been delayed. Oscar season seems yet another casualty of the pandemic.

The movie is, essentially, about the movies…

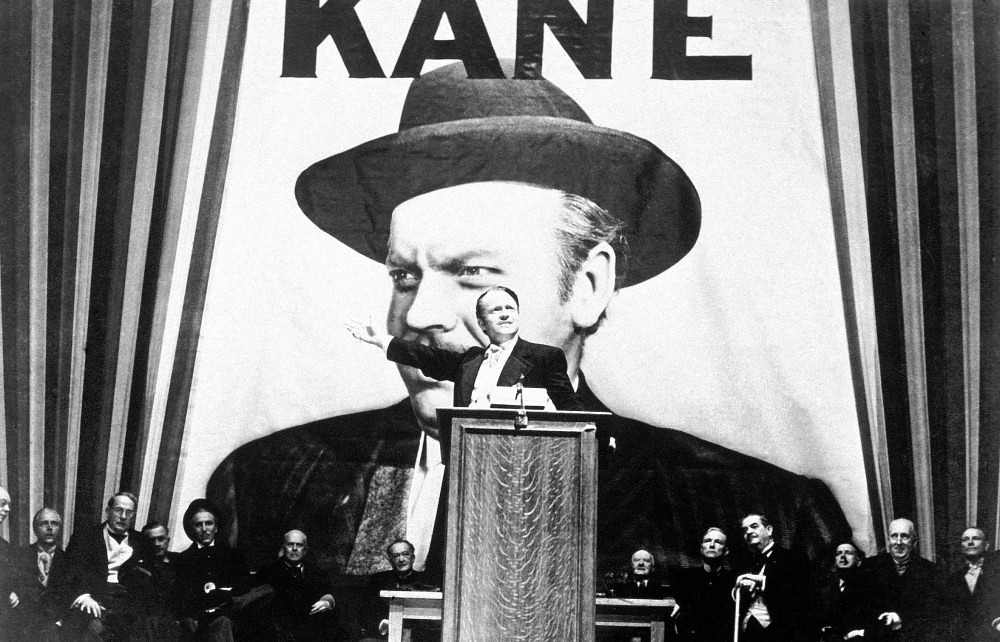

But if you still have that need for cinematic drama and Hollywood spectacle, David Fincher’s Mank will fill that void. The movie is, essentially, about the movies, and it has all the makings of an award-season darling. The film chronicles the true story of screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, played by Gary Oldman, as he races to finish the screenplay of Citizen Kane in 1940. Citizen Kane, still atop the list of the greatest films ever made, tells the story of enormously successful but conflicted newspaper titan, Charles Foster Kane. Basically, Mank is about how Herman Mankiewicz was inspired to write that famous story.

Mank’s plot is nonlinear. The principal narrative follows Mankiewicz drafting Citizen Kane, but we spend most of the film in flashbacks to years prior. Fincher sends us to the early 1930s, where Mankiewicz is a talented screenwriter at MGM studios, unafraid to speak his mind and deride his more corrupt colleagues. Mankiewicz’s antics earn him formidable rivalries with MGM producers and newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst––with the latter serving as the inspiration for Charles Foster Kane.

Another flashback takes us to 1934, in the midst of a heated California gubernatorial election between Republican Frank Merriam and muck-raking journalist-turned-doomed-Democratic-candidate Upton Sinclair (played by Bill Nye!). Mankiewicz can only watch as Hearst conspires to have his newspapers run smear campaigns against Sinclair while Hearst’s allies at MGM create propaganda films that paint Sinclair as a communist.

Mankiewicz is not shy as a social critic: a trip to Hearst Castle in 1937 sees Mankiewicz at a costume party drunkenly bemoaning Hearst for his crooked newspaper monopoly. By the third act, the past catches up to the principal narrative. Mankiewicz, now an alcoholic Hollywood exile, creates the character of Charles Foster Kane with the intent of illuminating the greed and excess of William Randolph Hearst.

We are not guided into this world, but rather thrown into it.

You won’t like Mank if you don’t like Mankiewicz. Gary Oldman as the titular Herman Mankiewicz is in practically every frame. His character is always boozing, smoking, or making snarky comments, similar to his performance as Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour. Oldman won best actor for that role and might secure another nomination in 2021. He is able to capture Mankiewicz’s self-destructive and assertive personality through his peculiar vocal delivery and witty one-liners that make the character distinctive and memorable.

There is a scene in which a producer tells Mankiewicz his draft of Citizen Kane is too dense, nonlinear, and “asking too much of a motion picture audience.” If these are the reasons Citizen Kane became American cinema’s crowning achievement, then Mank no doubt tries to emulate it. Mank itself is nonlinear and consists primarily of rapid-fire, high-context dialogue about people in Hollywood and events of the 1930s. We are not guided into this world, but rather thrown into it. Fincher partly relies on his audience to know the lore of Citizen Kane, to understand the contexts of 1930s American history, or at least have Wikipedia handy.

Perhaps Mank’s biggest tragedy is that we are forced to watch a David Fincher film on Netflix instead of on the big-screen. Fincher is one of the finest living directors with classics like Se7en and Zodiac under his belt, not to mention 1999’s Fight Club, which was recently reenacted on McGill’s campus. With such seamless fluidity, Fincher’s camera brings us to Hollywood nightclubs, movie sets, and smoke-filled script rooms.

But Mank looks and feels like no other Fincher film. The black-and-white images are embedded with artificial cracks and hairs to make the scenes feel like they’re coming from a projector in the 1930s. This sharply contrasts with the slick, modern design of films like The Social Network or Gone Girl, and the begrimed, underworld textures of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Fight Club. Fincher-mainstays Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross further cook up a jazzy, upbeat score that marks a tonal departure from Fincher’s darker projects.

If there is one thing the Academy loves –– and something we need in 2021 –– it’s movies about how awesome movies are.

Yet, Mank lacks the taut narrative momentum of Fincher’s first-rate psychological thrillers. Fincher no longer depends on edge-of-your-seat excitement, but allows characters’ lively, Aaron Sorkin-esque dialogue to tell the story and engage the audience. On occasion, the reference-heavy dialogue can feel confusing and the nonlinear story structure unfocused. The script doesn’t always tell you why a given moment is important, but allows the audience to assemble individual scenes into meaningful character arcs. Mank’s script was written by Jack Fincher, David’s late father, and the director had been trying to get it in production since the 1990s. Mank is a passion project for Fincher that he pulls off convincingly, albeit not masterfully.

If there is one thing the Academy loves –– and something we need in 2021 –– it’s movies about how awesome movies are. More than just a unique addition to Fincher’s storied filmography, Mank is a portal to a world that we can’t presently live in. It’s the world of extravagance, rivalry, and the crazy, problematic, and brilliant community of filmmakers, actors, and studios we so adore.