By Liam Mather

On the highway from Dublin to Belfast, which winds through the folds of great rolling hills, there are no signs or border stations to mark the place where the Republic of Ireland crosses into Northern Ireland. A generation ago, when the sectarian violence of the Troubles raged in the North, the border was guarded by militarized checkpoints. But today, peace stubbornly reigns in Ireland. Folks make routine trips across the border to golf, shop, and do business, and the green hilltops of South Armagh are no longer marred by British army watchtowers.

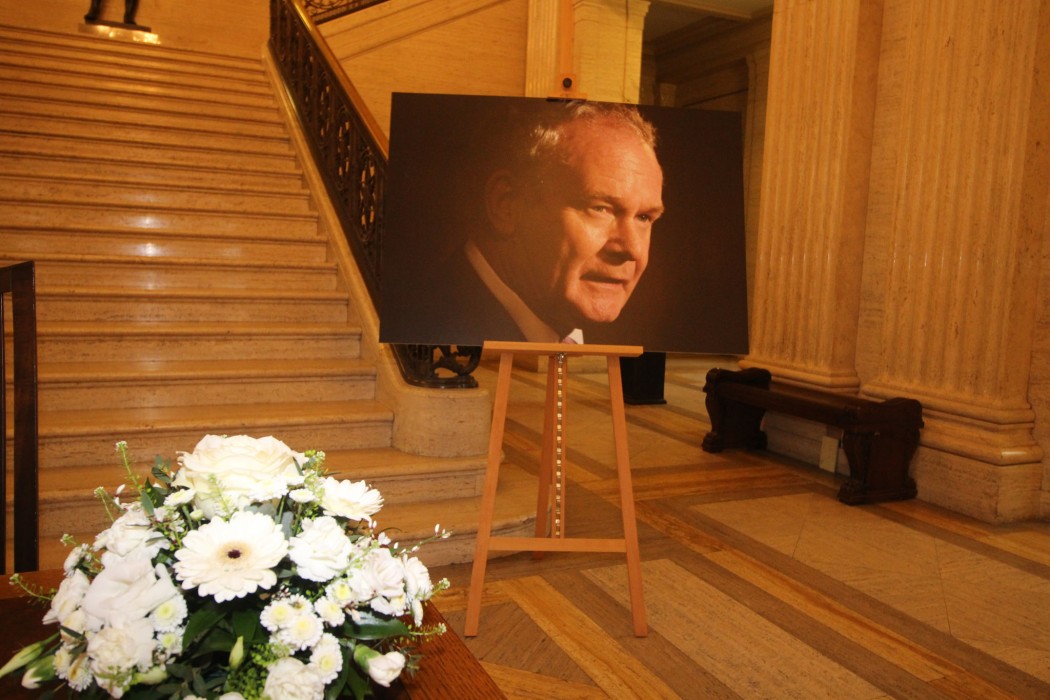

Last month saw the passing of a giant figure in modern Irish history, a man whose complex legacy is etched into this landscape and into the memories of those who call the island home.

Martin McGuinness, a former commander of the Provisional Irish Republican Army who spearheaded the Northern Irish peace process, and who most recently served as the Deputy First Minister in Northern Ireland’s power sharing government, died on March 21 in his native Derry. He was 66.

McGuinness, as the Northern leader of the Sinn Féin party, had served as Deputy First Minister since 2007, before a rare heart condition called amyloidosis caused him to resign in January.

Between 1968 and 1998, Northern Ireland was convulsed by the Troubles, a guerrilla war that claimed the lives of over 3,500 people. At stake was the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, which, since the partition of Ireland in 1921, has remained a constituent part of the United Kingdom. In the decades following partition, the Protestant-dominated provincial government of the North systematically discriminated against the Catholic minority. The Troubles began after a Catholic civil rights march in Derry on October 5, 1968, spiraled into violence. The main participants in the ensuing conflict were Catholic-nationalist paramilitaries, led by the IRA, that fought for a united Ireland; Protestant-unionist paramilitaries that defended Northern Ireland’s membership in the United Kingdom; and British state security forces.

Alongside Gerry Adams, McGuinness was the most prominent nationalist leader of the Troubles. Born in 1950, McGuinness grew up in the Bogside, a working-class Catholic neighbourhood in Derry and a hotbed of nationalist unrest. At 18, he became a gunman for the IRA; by 1972, he had risen to second in command of its Derry chapter. According to nationalist informants and security analysts, McGuinness then served on the IRA Army Council, and as IRA chief of staff, during the late 1970s and 1980s. McGuinness oversaw the group’s terrorist attacks of this period, which killed 1,781 people, including 644 civilians.

“We don’t believe that winning elections and any amount of votes will bring freedom in Ireland,” McGuinness told the BBC in 1986. “At the end of the day, it will be the cutting edge of the IRA.”

“We don’t believe that winning elections and any amount of votes will bring freedom in Ireland,” McGuinness told the BBC in 1986. “At the end of the day, it will be the cutting edge of the IRA.”

But after two decades of bloodshed, McGuinness concluded that his political aims could not be won through violence. In 1990, he began secret talks with the British government, which culminated in an IRA ceasefire in 1994. He was the head IRA negotiator in the ensuing multi-party talks that produced the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and ended the Troubles.

The deal set up a power sharing arrangement, whereby the Northern Irish executive would be run by both unionists and nationalists. It also established the consent principle: Northern Ireland would remain in the United Kingdom unless a popular majority of its residents supported Irish unification in a referendum (unionists continue to make up a majority). Although tensions persist between the North’s two political communities, the agreement has proven remarkably durable.

In the wake of McGuinness’s death, nationalists have mourned their former leader, and political figures from around the world have highlighted his role as a peacemaker.

Bill Clinton, whose administration brokered the peace deal, delivered a passionate eulogy for McGuinness at his funeral service, which was held last Thursday in the Bogside and attended by over 25,000 people.

“He believed in a shared future, and refused to live in the past, a lesson all of us who remain should learn and live by,” Clinton said.

Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister during the peace negotiations, also praised McGuinness for embracing reconciliation.

“I will remember him with immense gratitude for the part he played in the peace process, and with genuine affection for the man I came to know and admire for his contribution to peace,” he said.

But others have emphasized the early, violent chapters of McGuinness’s life.

On Remembrance Sunday, 1987, the people of Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, were gathered at the town cenotaph to commemorate British war dead, when an IRA bomb exploded, killing 11 and injuring 63. The “Poppy Day massacre” was one of the most controversial attacks of the Troubles and captured the world’s attention.

Stephen Gault, who witnessed his father, Samuel, die in the blast, worries that McGuinness’ complicity in attacks on innocent civilians will be forgotten.

“I will always remember Martin McGuinness as the terrorist he was,” Gault said. “If he had been repentant my thoughts might have been slightly different. But he took to his grave proud that he served in the IRA.”

McGuinness deserves acclaim for being an architect of the peace deal and its chief salesman to the nationalist community. But his legacy as a peacemaker cannot—and should not—be untangled from his violent past.

The IRA may not have embraced the peace process had it been pushed by a dovish nationalist.

The IRA may not have embraced the peace process had it been pushed by a dovish nationalist. Similarly, the British and unionist camps took McGuinness’s overtures seriously because they knew he was a fiercely committed militant who commanded the loyalty of the IRA. As journalist Fintan O’Toole has noted, the great contradiction of McGuinness’s life is that his political credibility was “built on a time when his orders condemned many to brutal death.”

Nonetheless, the passing of McGuinness has created a leadership vacuum in the nationalist community as winds of political change are sweeping the British Isles.

Last Wednesday, Theresa May, the British Prime Minister, formally triggered the two year negotiating process for extracting the UK from the European Union. May has promised a “hard Brexit”: the UK will seek to impose immigration restrictions on EU citizens and leave the common market.

Such a program will almost certainly destabilize Northern Ireland. To restrict immigration from the EU, May must resurrect controls along the North-South Irish border. The free movement of people within Ireland was a key nationalist demand during the peace negotiations and has been critical for post-conflict reconciliation efforts.

Moreover, Northern Ireland has become heavily dependent on free trade with the Republic since 1998. Many crucial industries, like dairy, are deeply integrated between North and South. This economic relationship has been facilitated by joint membership in the EU common market. May lacks both time and leverage to negotiate a free trade deal with the EU in the next two years. Under EU rules, the Republic cannot pursue a separate deal with the UK; following Brexit, it will have to apply the EU external tariff on Northern imports. The Northern Irish economy will likely be devastated.

The Brexit debacle has inspired a growing chorus of nationalists to demand a referendum on Irish unification, and there are renewed fears of a return to violence.

May has yet to offer a coherent plan to address these concerns, which motivated 56% of Northern Irish residents to vote “Remain” in the 2016 referendum. The Brexit debacle has inspired a growing chorus of nationalists to demand a referendum on Irish unification, and there are renewed fears of a return to violence.

And so McGuinness, the war-maker turned peacemaker, not only leaves behind a bitterly contested legacy. He leaves behind an island where the weight of history bears heavy, and where the political future is as foggy as a winter Dublin morning.