“Christelle, don’t you think that historically Black colleges and universities in the United States are counter-productive?” a fellow high school classmate once asked me.

All I knew back then was that historically black colleges and universities had been created in reaction to the American Civil War which had ended with freed Black slaves. In a nutshell, these institutions helped Black people gain higher education, which was often denied to them by historically white institutions. I didn’t understand what the environment of a university was like for Black students in contemporary society, so I replied with a simple, “It’s complicated.”

After my initial experience at McGill, I can say in all fairness that despite the 150 years that have passed since the end of the American Civil War, institutions such as Howard University are a blessing for young Black minds. It’s not complicated at all: as it currently stands, higher education in historically white schools such as McGill is simply not equitable.

It’s not complicated at all: as it currently stands, higher education in historically white schools such as McGill is simply not equitable.

We tend to view academia as this liberal safe space where all can share their thoughts free from either judgement or punishment. Where minorities, visible and non-visible, feel comfortable knowing that they are accepted. However, reality shows that universities such as McGill cannot fulfill that sentiment, however hard they may pretend. My experience as a Black student has demonstrated that these ideals cannot be fulfilled unless they are being acknowledged and remedied by the institution, faculty, professors, and students.

But first off, what is this so-called Black Experience that I am talking about? Well, this experience manifests into seemingly small things, such as a Eurocentric approach to classics and history. It manifests into having a developing areas political science professor tell you that the positive consequences of colonialism are industrialization and development. It manifests into having curricula with only articles and books produced by white men. It manifests into having classmates casually confirm that violent anti-colonial uprising is the leading cause of poverty in the ‘developing world.’ It manifests into being held as the representative of all ‘Black people and their nations.’ It manifests into having students casually ask if your “nice, silky, straight hair is real?” (Trust me, it has happened more than once). And, it manifests into having Black students failing or dropping out due to the heavy alienation and pressures that drive to mental health issues.

I have, more than once in the past two semesters, discussed with fellow Black students the dilemma of being pressured to succeed in a heavily alienating environment. They sought help from multiple faculty advisors, yet their anxieties were simply dismissed with the banal rhetoric to “suck it up.”

The Black Experience transcends the usual idea of “I am the only Black student in my class.” Rather, Black students are marginalized by poor curricula across fields and are not represented enough in the faculty and by student-run organizations (unless they are explicitly for Black students such as McGill’s African Students Society and the Black Students’ Network). We cannot put so much weight onto these two specific student-run organizations because this issue cannot be resolved by only Black people. It requires the proper integration of this community within higher education.

Black students are marginalized by poor curricula across fields and are not represented enough in the faculty and by student-run organizations.

Paternalistic approaches to education see Black students as the ones who shall educate their fellow classmates about ‘black problems’ and historical inaccuracies. For example, I vividly remember having to explain to fellow classmates that not all Black people are alike, and that assuming they are a homogeneous group is wrong. The underlining issue with that is not stupidity, but rather institutionally created ignorance.

These issues cannot solely be blamed on universities such as McGill. The lower levels of education often fail to provide a well-rounded understanding of the world. Such failures perpetuate misconceptions that further marginalize minority students. When we are failing to acknowledge the place of peoples of colour in society through biased interpretation of history, we are building societies that perpetuate injustices. The marginalization of Black students and other minorities is something that must be addressed by all – as a societal and academic problem.

As a woman of Haitian descent who has had the opportunity to live in South America, I carry with me experiences and knowledge that assert my Blackness. I see in these false assumptions made by students, professors, and textbooks, my inability to break through racism. I am indeed Black, but I am also an aspiring scholar, a woman, a pianist, a cinephile, and so much more. I am tired of waking up every single morning hoping that I won’t be triggered by fallacies made by professors and classmates. Though seemingly unintentionally, this thought consumes me to the point where I have thought of switching schools.

I am tired of waking up every single morning hoping that I won’t be triggered by fallacies made by professors and classmates.

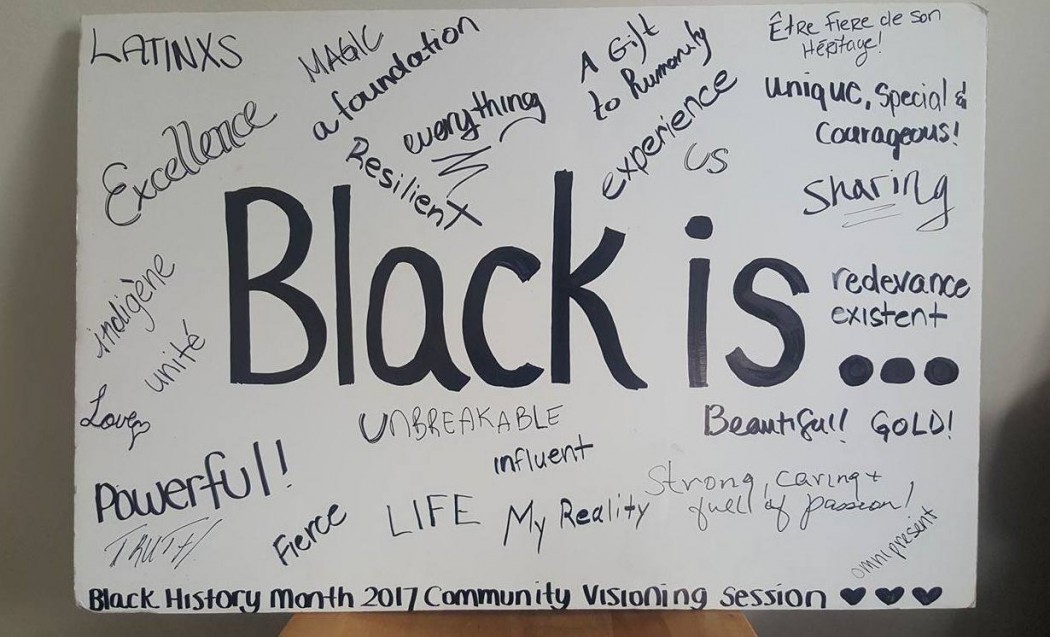

Although McGill has started being more inclusive to Black students, notably by officially holding Black History Month for the first time in 2017, this is not enough. Regardless of the month of the year, Black people face racism 24/7. Our history and peoples must be told and acknowledged every single day – from properly including us in academic discourse to letting us tell our stories.

We must also understand that a safe space, in the liberal sense, implies freedom of speech to the extent that it does not degrade people and their experiences. For example, events such as the latest Theology Thursday (where trans experience and scholarship is censured under the assumption that “intersex people do not exist”) must simply have no place at McGill. A line must be drawn between fallacy and freedom of speech. Perceiving such topics as merely ‘contentious’ alienates one from historical and scientific truths. It is important to look at things beyond the propaganda pushed by socio-cultural, economic, and political biases.

I am a Black Woman and I cannot speak for every single marginalized student at McGill. It would not be fair to their struggles. However, it is within my mandate to address my concerns regarding the proper integration of minorities at McGill – and I hope that you do so too. The McGill community, whether it be the administration, the faculty, the professors, the students or the associations, must actively stand up as one against racism, sexism, ableism, Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia. The inclusion of diversity in academia is essential for the betterment of our society.

It wasn’t long ago that explicit racial theory was part of the curriculum. Let’s not make it too easy to forget.