When COVID-19 pushed our university examinations to digital spaces, the McGill administration scrambled to maintain control. Online examinations meant students could “cheat”: they could check class notes, share answers with friends, or fish for questions on a paid Chegg account. As students adopted these new approaches, professors needed to adapt to assess comprehension and critical thinking rather than information regurgitation. Otherwise, a McGill GPA would lose its value.

Some of my professors tried to add depth to their exams. Multiple choice questions became absurdly convoluted riddles to delay an inevitable note search. Forward-only exams came into vogue, preventing students from revisiting a question after consulting with a group. Ultimately, most attempts to block shortcuts were futile. A lot of students did a lot better online.

But the crucial lesson here isn’t that online exams are broken – it’s that many examinations have always been this way. ‘Command-F’ is only a new iteration of the shortcuts and strategic cramming that students have been forced to engage in for years. Academic success has always been dependent on skills and resources irrelevant to course content. Online exams’ failure to evaluate deeper knowledge was entirely predictable in a university system that so heavily tests the ability to take tests.

Ultimately, most attempts to block shortcuts were futile. A lot of students did a lot better online.

Consider American standardized testing. Doing well on the SAT and ACT, as any guidance counsellor will tell you, is all about understanding how to take the test. For countless high schoolers, post-secondary aspirations depend on this artificially important skill set. Test-taking is best polished through private coaching and prep books, which are toll bridges to opportunity.

Given that the working world includes very little timed multiple-choice bubbling, the SAT and ACT are criticized for testing a skill with little real use later. But knowing how to speed through multiple choice examinations does continue to matter and stratify, as any McGill science student can attest. Most of our final exams assess the umbrella of test-taking savvy – time-management, process of elimination, best guesses – as much as the synthesis of course material.

What are we really doing in the fieldhouse besides searching through a bullet-point document in our heads, one designed to cover testable material for a day before falling away in subsequent disuse?

The SAT and ACT do test ability in reading, grammar, and math. University exams do require students to consolidate relevant information. However, these skills are flattened by the rapid, shallow assessments to which they are applied. What are we really doing in the fieldhouse besides searching through a bullet-point document in our heads, one designed to cover testable material for a day before falling away in subsequent disuse?

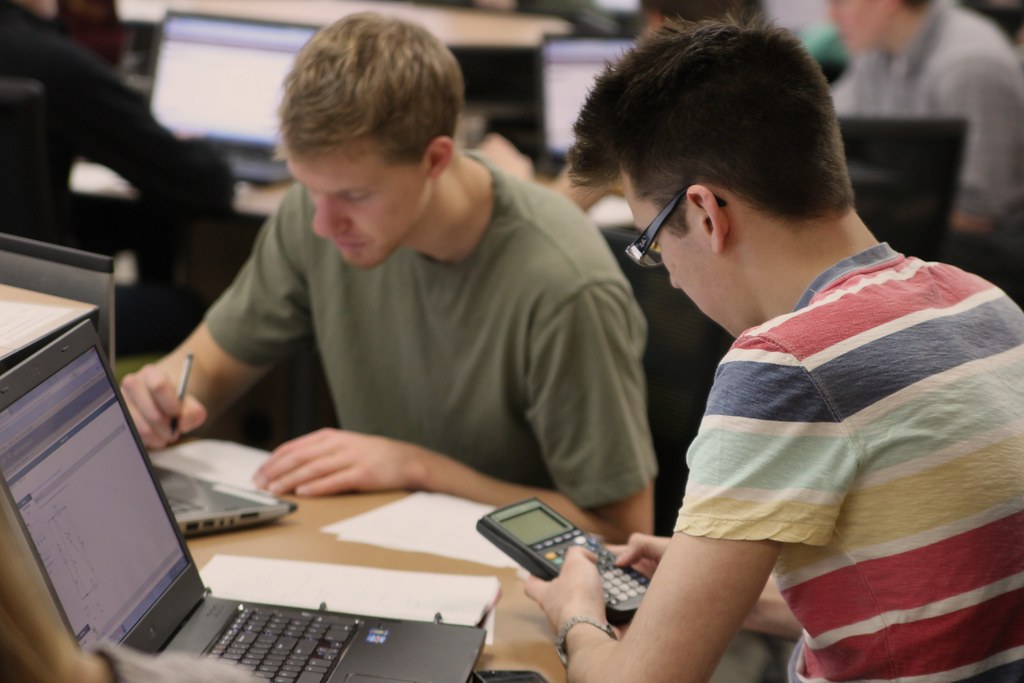

During my time at McGill, I’ve made efforts to avoid thinking. I stopped registering for math and computer science courses because I felt uncomfortable working on problems I might never solve. I ruled out an English minor because I was hesitant to stake my GPA on long answer questions and subjective grading. Though I’ve enjoyed my major, my time in university isn’t just a story of academic passions or weaknesses or even bird courses. The types of tests I did and didn’t take shaped my university experience more than I wish to admit. That submission is my loss, and the loss of numerous other students.

McGill students have spent the past year painfully aware that we aren’t learning in a meaningful way online.

Online evaluations laid these tendencies bare. McGill students have spent the past year painfully aware that we aren’t learning in a meaningful way online, while seizing every opportunity to study less and game examinations more. We’re a cohort of educational opportunists – it’s how we’ve been pressured to study from the moment we arrived at McGill.

As we gradually return to in-person schooling, I hope professors build on initial efforts to reduce workload while focusing on comprehension-based testing. And I hope us students don’t forget what online learning did actually teach us: we miss the interactive classrooms, the packed tutorials, the tangential professors, and the thrill of coming up with a solution or a phrasing that isn’t just a search away.