By Nicholas D’Ascanio

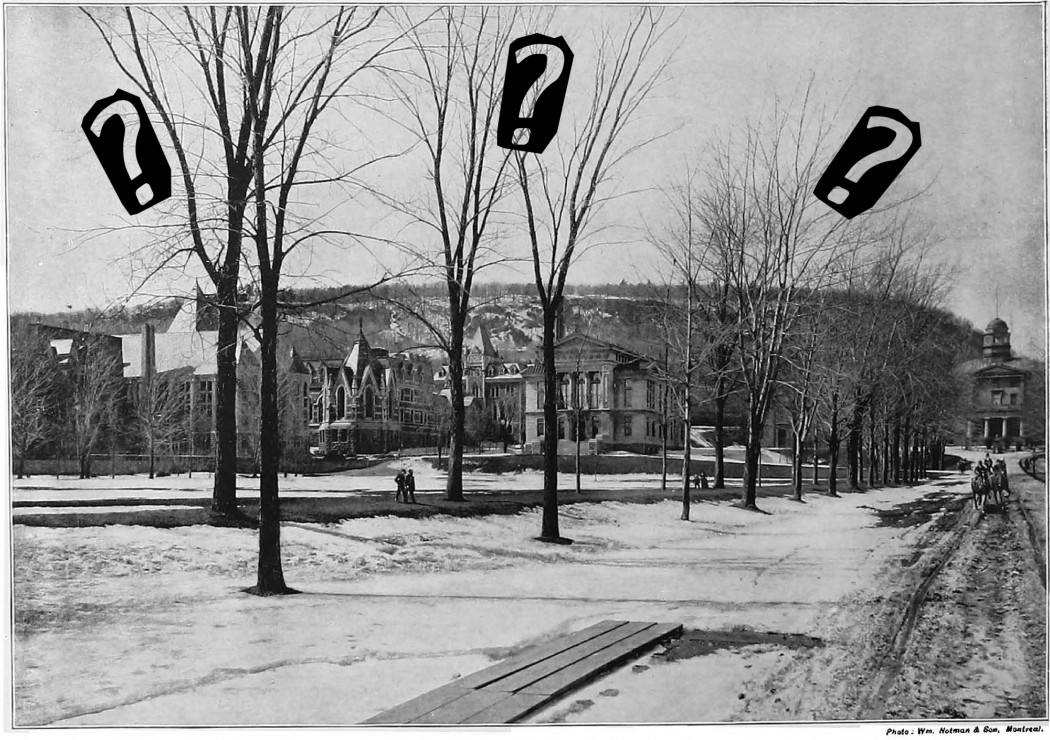

How much do you really know about your school? Beyond the QS rankings and the never-ending campus controversies, how much McGill history do you know? You probably know that Jacques Cartier stumbled on the Iroquois village of Hochelaga on lower campus, or that James McGill donated his farm to become McGill’s downtown campus. But there’s more to McGill than what the tour guides will tell you. A history of occult conspiracies, psychedelic mind control experiments, and the hidden treasures of an American president hide underneath the respectable veneer. Consider this article an introduction to the urban legends and offbeat history of McGill. These stories can teach us a lot about McGill and its place in the world, giving insight into the messy events and lives of people associated with McGill. Sometimes the greatest truths are found on the margins of the believable.

The McGillian Who Killed Houdini

Among our alumni we count a man who killed the great magician who had escaped death many times before.

On Halloween in 1926, the famous illusionist Harry Houdini died from a ruptured appendix in Detroit. Anyone who’s seen the John Hughes hit Planes, Trains, and Automobiles knows how it happened. “You could have killed me slugging me in the gut like that … that’s how Houdini died ya know!” so says John Candy’s character. But the circumstances surrounding Houdini’s death are even wilder than the 80s Thanksgiving buddy comedy, and have a direct, fatal link to McGill. Weeks before he died, Houdini gave a lecture at McGill on debunking spiritualism and the supernatural – one of his favourite topics. The story, as recounted by students Jacques Price and Sam Smilovitz, is that a McGill Divinity School student, J. Gordon Whitehead, approached Houdini and demanded he prove he really was as invulnerable as he claimed. Houdini apparently accepted the challenge and Whitehead swiftly punched him several times hard in the abdomen. Price recounts that Houdini had been nursing a broken ankle and wasn’t able to stand and prepare himself in time. After a few blows, Houdini winced and motioned that he had had enough. A few weeks later in Detroit he was sick with abdomen pain and a high fever, but insisted he go on. He was barely able to finish his act when he was finally rushed to the Grace Hospital. There, he was diagnosed with peritonitis caused by the rupture of his appendix. Despite initially seeming to recover, Houdini died Halloween afternoon.

Supposedly, the hits to the stomach directly caused Houdini’s death, but there is no clear medical link between abdomen trauma and appendicitis. As Snopes.com points out, it may have been simply that Houdini mistook his already swollen appendix for discomfort from Whitehead’s assault and so refused treatment. Whatever the exact circumstances of Houdini’s death, Whitehead played a central role. Among our alumni we count a man who killed the great magician who had escaped death many times before.

Lincoln in the Library

Trudging your way up or down the McLennan stairs, you may have noticed the small white statue of Abraham Lincoln on the fourth floor. This statue is but the tip of the iceberg. McGill’s Rare Books and Special Collections boasts the largest collection of Lincoln memorabilia outside the United States. This includes dozens more sculptures and busts, thousands of letters and essays, several paintings, and even chairs from Lincoln’s White House. One of the most remarkable items is the journal of Dr. Charles Taft, who was with Lincoln the night he died, providing one of the most detailed accounts of the assassination. Dr. Joseph Nathanson, a McGill graduate and a professor of medicine at Cornell University, donated all of this. Nathanson started his Lincoln collection after helping his daughter complete a school project on the 16th President. Upon his death, he bequeathed the entire hoard of Lincolniana to his alma mater. The collection even contains a piece of the bandage used on Lincoln’s head after he was shot. There are definitely 152-year-old presidential blood flecks somewhere in the McLennan Library. So if any enterprising biology students want to clone the 16th President of the United States (Lord knows now is as good a time as any), they know where to start.

Stranger Things

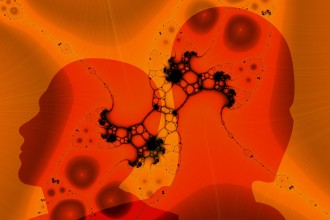

Right here at McGill was an example of the Cold War arms race at its most insane extreme: a frenzied attempt at real psychic warfare at the expense of innocent patients.

McGill’s MK Ultra, the CIA’s secret psychological warfare research program, connections have been discussed before in student media, but they bear repeating to fully understand how crazy things were. At various partner universities, one of these being McGill, mentally ill patients were forcibly subjected to a variety of dramatic experiments such as sleep deprivation and the ingestion of psychedelic drugs. The United States’ goal was drug-induced mind control that could give them the upper hand against the Soviets (who also thought this was a good thing to try). MK Ultra was the sort of program dramatized in movies like The Men Who Stare at Goats or more recently, in Netflix’s Stranger Things.

Located just above the McTavish Reservoir, the Allan Memorial Institute was, and is, McGill University Health Centre’s psychiatry department. In the 50s and 60s, the CIA contracted Dr. Ewen Cameron of the AMI to do MK Ultra experiments. Cameron turned Ravenscrag, formerly railway baron Sir Hugh Allan’s mansion, into his personal playground of psychological horrors. These experiments included intensive electroshock therapy, forced comas for days at a time, and the forcible ingestion of hallucinogens. Right here at McGill was an example of the Cold War arms race at its most insane extreme: a frenzied attempt at real psychic warfare at the expense of innocent patients.

Other Tidbits

Other McGill history tidbits abound. An eagle-eyed student can spot a plaque on Dawson Hall commemorating that during the Second World War, the International Labour Organization fled Geneva and set up shop on campus. Scottish students may be amused to read that James McGill’s gravestone in front of the Arts Building lists his birthplace as “Glasgow, North Britain.” This puzzling inscription is a unique North American relic of the unionism that gripped the British Empire in the 17th and 18th centuries. Scratch the surface and you’ll find many more examples of neat and bizarre McGill connections to peoples, places, and things around the world.

So keep your eyes peeled as you shuffle through the Y-intersection on a snowy day or check in to McLennan for another study session. You might just spot a piece of weird McGill history right in front of your nose. It could be an artifact donated by an obsessive alumnus or a suspiciously robust commitment to research ethics in the psychiatry department. Whatever the case, these stories can teach us a lot about our school and the hidden lives of the people who have walked its halls. The truth is almost always stranger than fiction.