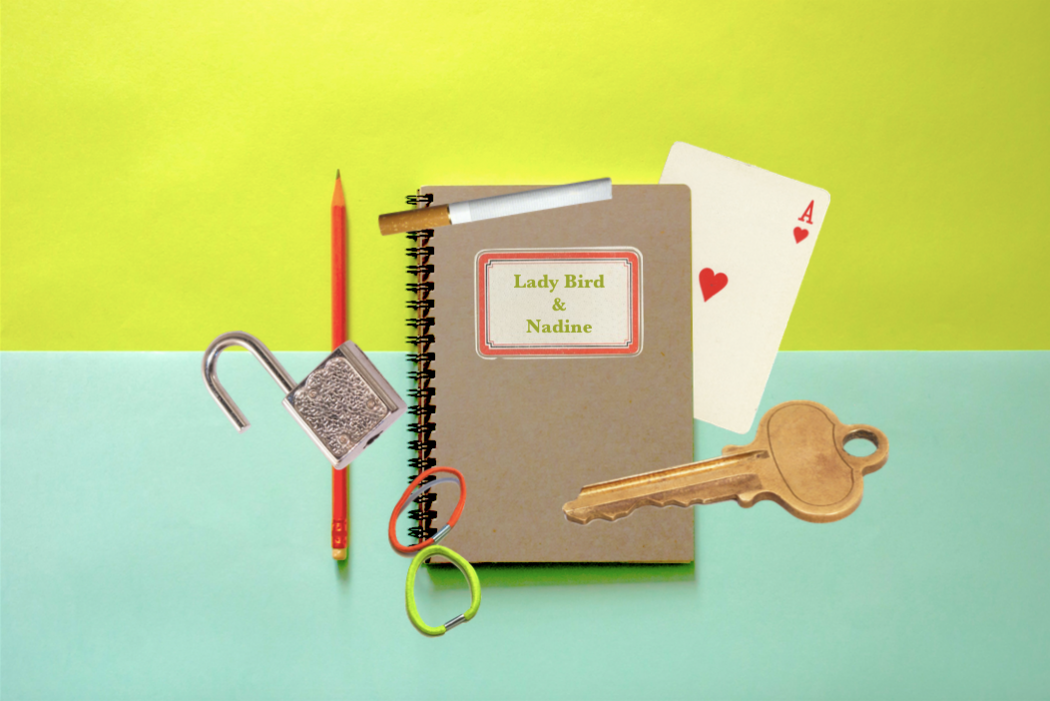

In the last few years, two excellent coming of age films have grappled with the interiority of their teenage girl protagonists, guiding their audiences through the labyrinthine ups and downs of being an adolescent on the brink of adulthood. Lady Bird was released in 2017; The Edge of Seventeen in 2016; both have two compelling, sometimes infuriating three-dimensional teen girls as leads; both are constantly and unnecessarily pitted against each other. As someone who finds it more appealing to consider these two films as being complementary to each other, and not as opponents in the Movie War™, I’ve thought about how things don’t really change for teen girls in the ten years between when Lady Bird and The Edge of Seventeen take place.

The former is a distinctly 2003 movie, grounded in the signifiers of that long-gone era: “Crash” by Dave Matthews Band playing softly on the radio, those extremely 2000s outfits that don’t really make sense but still count as clothes, news coverage of the Iraq War flickering across a television screen, the strangely scarce number of cellphones. The Edge of Seventeen mostly avoids a time stamp, but its soundtrack (A$AP Ferg, Anderson Paak, The 1975), Nadine’s texting, and the indication that it’s set a few years since her father’s 2011 death gives us the sense that we’re in the recent past. For all of these contextual differences, Lady Bird and Nadine are united in the way they process, react to, and engage with the teen experience.

…they’re both searching for some kind of human connection, and each film tackles the different trajectories of that experience with authenticity.

The films have a number of scenes in common with each other and with other teen movies: the house party, learning how to drive (or, perhaps more accurately, driving without knowing how to), the friendship break-up, and the big fight with mom. Yet at the heart of all these cultural and social milestones is an emotional centre, guiding the characters as they sort through their internal and external lives. They both wander around their house parties, Lady Bird perhaps more aimlessly than Nadine, and Nadine perhaps more anxiously than Lady Bird — but they’re both searching for some kind of human connection, and each film tackles the different trajectories of that experience with authenticity.

That search for human connection rarely goes smoothly. Sometimes, it begins with a fight; Nadine, enraged by her best friend Krista’s relationship with her brother Darian, is forced to branch out. Other times, it triggers one, as Lady Bird starts hanging out with new people and drifts away from her best friend Julie. Though she eventually hits it off with Erwin, Nadine spends a lot of the movie floating on the periphery of other people’s conversations, feeling virtually invisible, never quite knowing where she fits into the ever-changing slots of the social puzzle. The people that Lady Bird hangs out with think she’s weird, which is another kind of invisibility because it’s a different version of being misunderstood. It’s all very sad and very real.

Nadine and Lady Bird have crucial moments with teenage boys (both are dark-haired and mysterious and vaguely tired-looking), illustrating little things about sexual relationships: the mechanics of consent, as well as the violation of hooking up under false pretenses. The Edge of Seventeen deals with its consent scene with subtle humility, never calling attention to itself for such a welcome portrayal: Nadine is vocal about what she does and doesn’t want, and the guy she’s with always backs off, even if he’s an asshole about it. Lady Bird wants to have sex, and she does, but she’s upset to find out that it happened under different circumstances than she’d thought. They both cry. These are sad scenes. However, it feels good to have moments like this, which emphasize the importance of communication and respect, never resorting to violence.

There is a lingering feeling of being trapped and on a never-ending search for validation.

Even as they search for connection with other people, the characters wrestle inwardly, unsure if they have any characteristics that will redeem them to themselves. When her mother says she just wants her to be the best version of herself, Lady Bird looks at her pathetically and asks: “What if this is the best version?” For most of the film, that sadness is manifested as restlessness, Lady Bird feeling stuck in her small Californian hometown — she wants to be bigger and better than whatever she is there, and that can only happen in a different place. Something similar occurs with Nadine, who struggles with self-loathing treated so matter-of-factly that it’s both jarring and refreshing to watch her say, “I had the worst thought. I have to spend the rest of my life with myself.” These lines, in both of these movies, are a perfect crystallization of what so many teenage girls go through in a world where they’re not really valued, some even less than others. There is a lingering feeling of being trapped and on a never-ending search for validation.

These movies share other little slices of life, but capture none with as much depth as these emotional voyages, which kick them down and eventually lead them to a better place (and I don’t mean Lady Bird moving to New York). That’s why it feels so silly to deem one better than the other, when they hit so well as companion pieces; one set in 2003, the other roughly 12 years later, both with important things to say about two teen girls who are imperfect, but utterly human.