In the name of combating climate change, the Western World has paradoxically positioned itself as the saviour and the villain. The irony is that while they compose symphonies of climate promises, pledging to slash emissions and cap global warming, they subtly pass the buck to the world’s developing nations, many of whom are still grappling with the basics of economic survival. This disparity is not just blatant—it’s ethically questionable, particularly considering the energy consumption dichotomy between the West and the developing world. Considering its current wide, expressive use, this definitely falls within the catch-all of Colonialism.

Let’s decode the paradox. Having feasted on fossil fuels to build towering economies, the West has ‘dined and dashed,’ waving the climate banner, cautioning Africa to shy away from the resources that could catalyze their development. Take a moment to digest this: the average energy consumption per person in sub-Saharan Africa is a paltry 185 kilowatt-hours annually. In stark contrast, the figures stand at approximately 6,500kWh in Europe and a staggering 12,700kWh in the United States. That’s right. The yearly energy consumption of one American fridge outstrips that of a typical African individual. This disparity isn’t just a statistic; it’s a glaring billboard of inequality. It’s the climate change narrative’s greatest irony: those who ignited the carbon bomb are now preaching the sermon of sustainability.

Energy is not a luxury but a basic need—a catalyst for development.

The West’s pledge to cease financing new fossil fuel projects rings hollow in the face of these realities. The Glasgow Statement is a coalition of rich, affluent countries who pledged at COP26 to halt almost all financing of new fossil fuel emitting projects internationally. Why? Because while they choke funding for African gas projects, they are actively building new gas pipelines within their borders. It’s the classic ‘do as I say, not as I do’ philosophy.

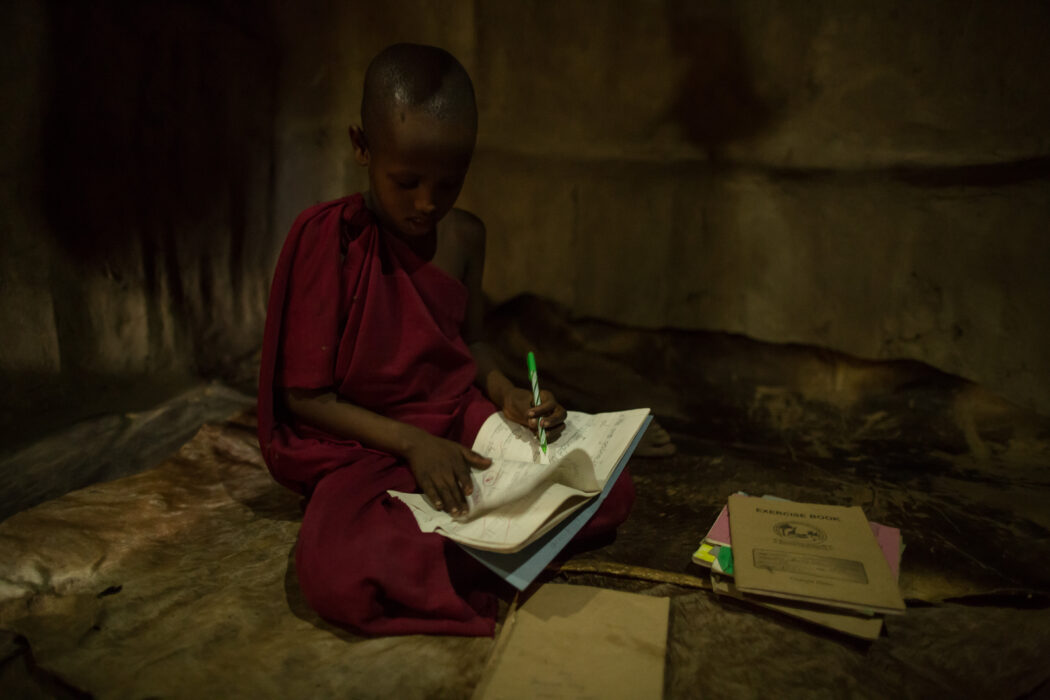

For the third world, the energy famine is a simultaneous cause and consequence of poverty. Energy is not a luxury but a basic need—a catalyst for development. The West’s hypocrisy comes into a defined focus when we see rich, preachy nations comfortably nestling in their fossil-fueled warmth while cringing at the prospect of underwriting energy projects in Africa. It’s like a king promising his subjects a feast and then delivering them the crumbs.

Renewable energy is a noble, even necessary, goal; however, it isn’t the silver bullet for Africa’s immediate energy needs or the world’s need for more renewable energy projects. Solar and wind projects require hefty upfront costs, and their reliance on Mother Nature’s whims doesn’t provide the consistent energy flow to keep industries humming and economies growing.

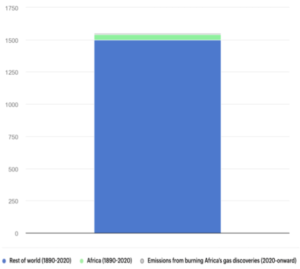

In the context of Africa’s industrialization, the projected increase in natural gas demand—integral for key industries—aligns with an expansion in renewables for electricity. Moreover, unexploited natural gas reserves estimated at over 5 trillion cubic meters could provide essential support for critical sectors, with the next three decades of their use only contributing a mere additional 0.5% to Africa’s global emissions share, totalling 3.5%. The additional half percent equates to the minuscule line of grey above the green, representing Africa’s already irrelevant share of emissions. Consequently, the shift to ‘sustainability’ could disrupt economies, especially those already reliant on oil exports.

Though imperfect, gas-fired plants offer a reliable and affordable bridge between a continent like Africa’s current state and a renewable energy future. Ironically, The Rockefeller Foundation’s one billion dollar investment in distributed renewable energy, in partnership with the Ikea Foundation, manifests a striking irony: a dynasty built on oil now finances the green energy revolution. This is not a guileless commitment to environmental sustainability. It is a strategic rebranding and investment opportunity to help shed the sins of their forefather, good old John D. Instead of the continent being the West’s test site for impractical ideas, the oil and gas industry is a solidified sector that can become a springboard for globalized economic benefit and trade between first and third-world nations. The benefits lay bare, yet the West continues to dangle the Damocles sword of climate catastrophe over Africa’s head.

The ethical case for fossil fuels is not a carte blanche approval for their unabated use nor an excuse to ignore the pressing realities of climate change.

The ethical case for fossil fuels is not a carte blanche approval for their unabated use nor an excuse to ignore the pressing realities of climate change. Instead, it’s an appeal for fairness, support, and the right to development. It’s a call to recognize that while the ultimate goal is a world running on clean energy, the path for some needs to include using fossil fuels. It’s about acknowledging that a villager’s first electric lightbulb and a child’s first cold vaccine from a refrigerated supply in a rural clinic cannot wait for the world’s perfect green solutions. The climate debate needs a recalibration that integrates essential compassion, historical responsibility and practicality. The West must shed its deeply hypocritical facade and acknowledge its real and substantial role in the climate crisis as a first step to offering tangible support to Africa’s energy journey and its consequent development.

It’s a call to recognize that while the ultimate goal is a world running on clean energy, the path for some needs to include using fossil fuels.

What’s the way forward then? Equity. Only 25 billion USD a year (1% of global energy investment today) is required to gain universal access to modern energy. Technology transfer, fair trade policies, and support for infrastructure development also play vital roles. Acknowledging the near-term market exportation opportunities, such as the EU’s goal to halt Russian gas imports by 2030, provides a stable role for the West to take, driven by the free markets. It cannot ask the developing world to fight climate change with their hands tied and resources stretched. It’s high time the narrative around fossil fuels and climate change reflected the complexities of our intertwined fates. This isn’t a villain-and-hero story. It’s a tale of historical burdens, ethical responsibilities, and the urgent need for empathy in policymaking. The developing world isn’t the climate enemy; poverty is. And suppose we’re to win this fight. In that case, it’s crucial to provide every country with the right tools and support to build a sustainable future without sacrificing the present.