According to the Student Demographic Survey (Diversity Survey) by McGill University, language—namely the bilingualism present on campus—is inextricably woven into the fabric of this institution. In fact, the diversity survey reports that “63% of respondents indicated that language was a very significant component of their identity.”

With the goal of rendering McGill a more inclusive environment, the survey invited a sample of 9000 undergraduate, graduate, and diploma-seeking students to anonymously answer questions regarding their perceptions of the university’s “diversity climate”. The response rate was 23 percent. Although the survey was conducted several years ago, the results are still undeniably relevant today. The McGill student population has only become more culturally and linguistically diverse since then, and while the university has taken steps to alleviate the identified issues regarding perceived intolerance, certain concerns still persist.

Language acts as a medium through which students lead their day-to-day lives, directly impacting two major spheres of university life: academics and social relationships. Unique to McGill is the campus culture that emerges from the dichotomy of a predominantly English-speaking university in an otherwise French-speaking city.

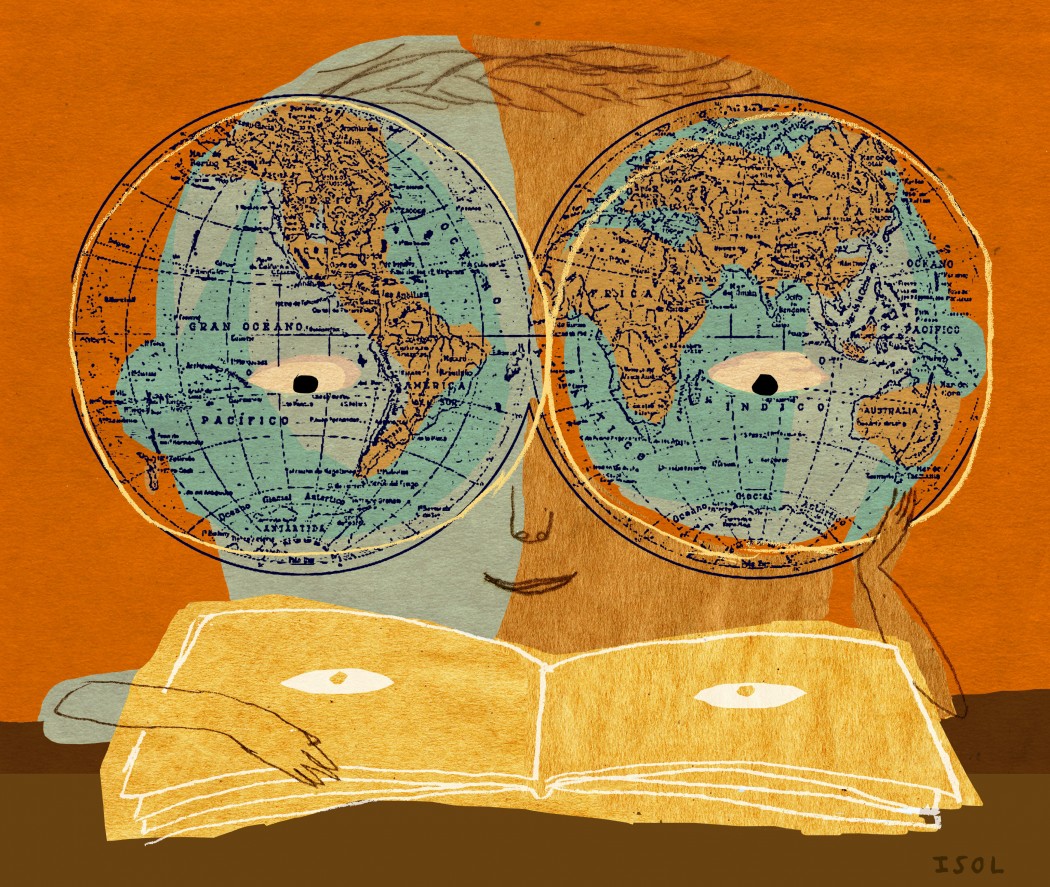

New York Times best-selling author Rita Mae Brown once said, “language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going.” If this is true, what does the multilingualism at McGill suggest about its students and the university’s identity as a whole?

Officially Bilingual, Unofficially Biased

McGill’s policy allows students to submit their work or written exams in French, which acts as a distinct reflection of the university’s presence in Quebec. “From [a francophone student’s] point of view, I think the bilingual nature of Quebec facilitates their participation at an otherwise English-speaking university,” commented Prof. Charles Boberg, an expert in language variation and change, dialectology, and North American English.

While this provincial policy was designed to aid French native speakers, few students actually take advantage of this policy due to the perceived disadvantages or caveats that accompany it.

“Some profs are not 100 percent proficient in French, or they don’t explicitly promote submitting assignments in French, so if a student were to submit their assignment in French, it’d be marked by a TA. I can imagine that this would deter many francophone students from taking advantage of this policy, because they’d prefer that the professor reads their work,” surmised Lilly Gates, a U2 Environment and Anglophone from Ontario.

In addition to the lack of bilingual professors, students may opt out of using the policy because courses are taught in English, which carries over when discussing related material outside the classroom.

“There are many technical terms that we learn in class that I wouldn’t even know how to translate into French. When we have conversations about the text, it’s just easier to talk about it in English – especially in group projects with people who have varying French abilities, where there’s really no other choice,” said Telli Riazrafat, a U2 International Business student and bilingual Montreal native.

Many francophones are proficient in English—a certain level of English competency is actually necessary to apply to and thrive at McGill, where the language dominates.

The 2009 Diversity Survey showed that “a minimum of 89% of respondents reported that they were either very good or excellent in each of the following English skills: writing, understanding, reading and speaking.”

Regardless of the reason, the infrequent application of this policy suggests that it serves as little more than a formality. The reality is that Francophones are extensively using English, which is often their second language, in the academic arena.

Although the above statistics show that most McGill students have a firm grasp of the English language, the anxiety associated with speaking in a non-native tongue can become amplified in a classroom or group setting.

“When we have group projects, I’m already nervous about presenting my ideas to a whole group, but it’s even more stressful when there is the added fear of not being able to translate my thoughts properly, and facing the judgment of others because English is not my first language,” said Lesly Yao, a U2 Finance student and Francophone from Tahiti.

The Social Barriers of Language

When it comes to the social aspects of university life, students often notice a divide between English and French speakers. Boberg offered an intuitive explanation for this observation when he stated that “language is obviously a factor of friendship. If you feel limited expressing yourself in a particular language, that’s going to be an important barrier to a friendship with someone, and that’s often why people stick to certain language groups.”

While there are many complex facets of language that complicate interactions between speakers of different linguistic backgrounds, one of the most common is that the nuances of phrasing tend to get lost in translation.

Erica Bossard, a U0 Arts and Science student who is also a German and French speaker from Switzerland, described a confusing experience that resulted from these subtle discrepancies.

“At the beginning of my studies at McGill, I had a problem with English, because English-natives, such as Americans, tend to speak in a superficial way. They’ll say things like ‘yeah let’s make plans, I’ll talk to you soon’ but don’t necessarily mean it…it seems to be more of an expression. As a German speaker, I took their words literally. When the expectations set for you by your own language don’t translate over, you can begin to feel very isolated.”

The technical term for this sentiment is “illocutionary force.” As described by Boberg, “the illocutionary force of a statement is often difficult for second-language speakers—who have not grown up in a culture—to acquire. It’s easy enough for someone to come as an adult and learn a new language, and have a reasonable command of the vocabulary and grammar, but often the more subtle interpretations of certain expressions, statements and ways of speaking is culturally acquired knowledge that may be difficult to grasp if you’ve missed the socialization period as a child.”

Inadvertent Inequity

Historically, language has always been a source of discordance, and it’s easy to see why—language is deeply personal. It’s how individuals become familiar with their community’s way of thinking, feeling, and understanding the world. However, in the context of a university, such discordance, reflected in the disparity of students with differing backgrounds and how they approach academic and social settings, becomes problematic when it leads to discrimination.

Considering the fact that McGill is an esteemed university that prides itself on its international reach and diversity among students and staff, it may come as a shock that “overall, 22% of respondents reported some form of discrimination based on language by fellow students and 17% by McGill employees,” according to the diversity survey.

The study reported a correlation between the number of languages learned in childhood and the likelihood of perceived discrimination: “[R]espondents who reported learning only one language in childhood (regardless of the language) were more likely to report some discrimination by fellow students on the the basis of language than respondents who learned two or more languages in childhood (26% vs 17%).”

Boberg proposes an explanation for this correlation, stating that “these results can perhaps be explained by people from bilingual or multilingual environments being more accepting of linguistic diversity and not always being addressed in their first language, so perhaps they’re less likely to identify that as an instance of “discrimination” when it happens at McGill.”

Although the McGill administration has made efforts to fight discrimination since the publication of the survey in 2009, tension between Anglophones and Francophones inevitably remains.

“I was doing a group project where the five other members were Francophone. I never felt outright discriminated against, but there were times when I definitely felt alienated when my group members would discuss ideas in French and I couldn’t contribute to the conversation. I don’t think that was intentional; it’s only natural for them to revert back to their native language,” expressed Samantha Li, a U3 Strategic Management and native English-speaker from Calgary.

Bossard agrees that any discerned discrimination does not arise from ill-intent, but rather the natural tendency for students of similar language backgrounds to gravitate towards one another—not only Francophones, but Anglophones as well.

“Since we’re at an English-speaking university, people tend to have a one-way perspective, looking at French groups as being cliquey or exclusive, when I’ve noticed just as many English speakers congregating together in the same way.”

Moving Forward

McGill is a university that celebrates multilingualism, multiculturalism, and diversity, with a student body and faculty that are constantly taking steps towards creating a more welcoming and tolerant environment, including efforts to bridge the language gap. Many incoming McGill students expressed that they wanted to better their French skills, with “(40%) reporting that they were interested or very interested in improving their French writing. Not surprisingly, those who rated themselves as less proficient were more likely to be interested in improving their skills,” according to the survey. Beyond simply expressing an interest in improving their skills, “18% of all respondents stated that they studied the French language formally (classes) and 17% indicated that they took informal steps to improve their French (e.g., via conversational groups).”

As an international institution, McGill acts as a hub for a multitude of cultures, allowing students to represent the essence of their home community via language, which can ultimately contribute to a more understanding university culture.

Studies such as these inform us that there is still more improvements to be made, but also reminds us that McGill is constantly working towards a better understanding of its students and their varied backgrounds. McGillians hail from all corners of the world, and a celebration of this, rather than a further divide, can lead to a more tolerant tomorrow.