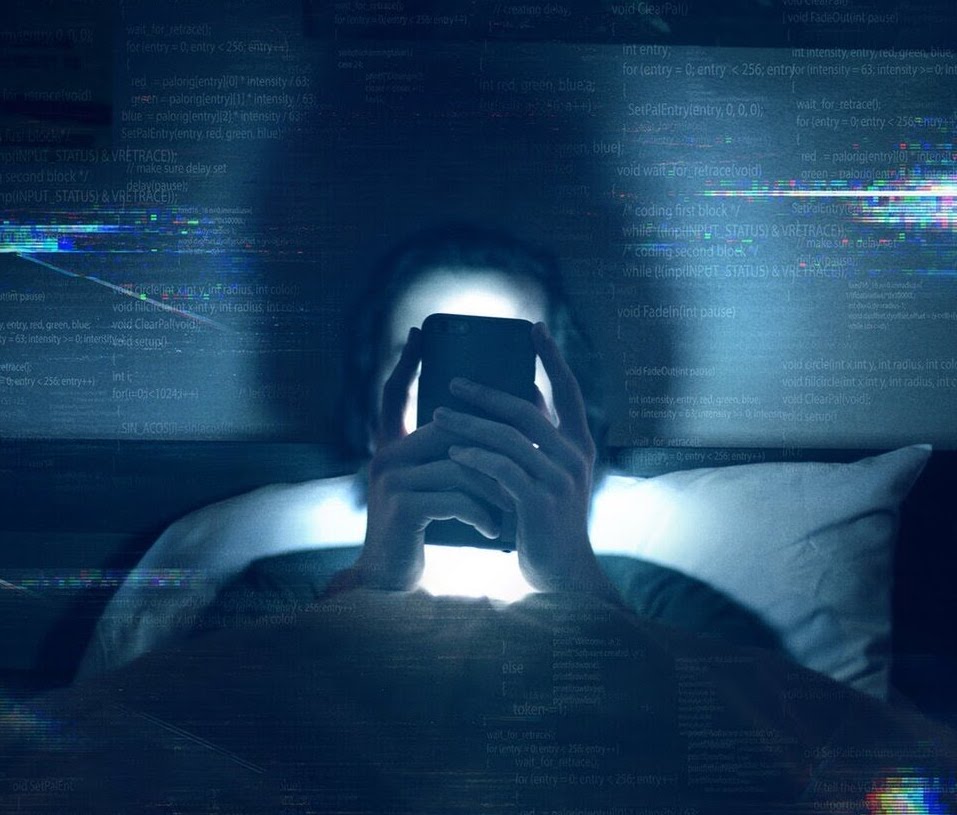

Our brains are being rapidly rewired to consume more and consolidate less. Social media algorithms have written humans out of decision-making processes, collecting and deploying individuals’ data in ways that none of us fully understand.

This disconnect between human and algorithm is the focus of Netflix’s bombshell documentary The Social Dilemma, released in January of 2020. In the film, Silicon Valley insiders describe the hidden mechanisms and motivations of Big Tech in a parade of pause-and-shake-your-head moments:

“If you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product.”

“The very meaning of culture is manipulation.”

“There are only two industries that call their customers ‘users’: illegal drugs and software.”

These enlightened mantras (of debatable accuracy) sent countless viewers—Boomers, Gen-X’s, Millennials—into a frenzy. Parents texted children. Great aunts sent out mass emails: You need to watch this. Critics hailed the film as an eye-opener, an unmasking of the harmful, self-reinforcing effects of social media.

But since watching, I’ve been bothered by a second disconnect, one that undermines the conversation the film is trying to have. The Social Dilemma, while highly informative, doubles as another attempt by older Americans to offload their unhealthy relationship with technology onto younger generations.

Like many tech pieces, studies, and conversations, this film is clearly designed by adults, for adults, to be about young people. These roles become clear during the documentary’s unorthodox dramatizations, which follow a fictional family dealing with your classic lineup of tech woes: phones at the table, cyber-bullying, compulsive stalking, political radicalization, and so on.

The Social Dilemma, while highly informative, doubles as another attempt by older Americans to offload their unhealthy relationship with technology onto younger generations.

The drama revolves around the children of the family. The youngest daughter bursts into relevance when she smashes her phone out of a timed lockbox with a hammer. Within an hour she is in tears over an online comment about her ears. The son, meanwhile, cracks after a two-day digital detox, slipping into deep digital rabbit-holes. Over subsequent scenes, he quits the soccer team, ices out his crush, and becomes essentially nonverbal as his phone woos him into the tactfully-named “extreme centre”. The dramatization ends with his arrest at a violent political protest. See, see, real-life consequences!

The issues these two children face are significant. Online content can be damaging and social media addiction is crippling, but many of these challenges are cross-generational. In fact, a 2018 report found that adults aged 35-49 spend more time on computers and smartphones than all younger age cohorts. Once TV is factored in, screen time is highest among adults over 50. The obsessive linking of youth and digital dependence in the media becomes even more patronizing in this statistical context.

Revelations in The Social Dilemma about unaccountable algorithms and our own neural rewiring don’t shock us; we’ve already been thinking about these processes.

Young people’s attitudes towards technology aren’t what parents think. For years, I’ve told my own parents that my peers and I are hyper-aware of our reliance on devices. We discuss these addictions often. We have developed new social norms to keep phones in pockets while sharing a self-deprecating rapport about living in the moment. We are learning to block websites, delete apps, and discard phones in a conscious effort to be functioning, productive adults.

In short, young people benefit from familiarity with tech and an in-touch social support system. Revelations in The Social Dilemma about unaccountable algorithms and our own neural rewiring don’t shock us; we’ve already been thinking about these processes.

Our elders, on the other hand, are more isolated from this social awareness. They lack important outlets for reflection and self-restraint. For example, most parents closely monitor their children’s screen time, but only 3% carefully restrict their own screen time around their kids. Media that frames tech addiction as a young person’s problem only deepens this culture of denialism.

Older generations have always used younger generations as a canvas for their concerns. Take the panic over youth drug use in the 60s and 70s, or dismay over explicit song lyrics in the 90s. Time and again, young people stand at the cultural cutting edge, creating, struggling, and adapting. Then they age, and the very people who learned to navigate cultures of drugs and parental advisories bemoan the digital subversion of today’s youth.

Except this time the parents are intimately involved. They’re as addicted as we are. The Social Dilemma glosses over this reality. Although the film was revelatory for some, it fails to adequately hold a mirror up to older tech users. It’s time we young people add to the discourse started by The Social Dilemma by expressing and documenting some of the urgent concern for our elders that they—rationally or not—express for us. From social dilemmas come social solutions.