I’m not a fan of early 20th century avant-garde art. Blasphemy, I know. I’m not saying I see no value in it – simply that I’d rather look at a Doré, than a Duchamp. If I have betrayed my lack of sophistication and aesthetic sense, it’s only to give new meaning to my takeaway from the “Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor” exhibit:

Calder’s work is brilliant.

This is no big revelation. Most people familiar with his art, including philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, will say the same. But, I was not expecting – given my artistic proclivities – to enjoy the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ retrospective on the American artist. And I did – immensely. So, for what it’s worth, I’d like to share my thoughts.

The exhibit celebrates Calder’s ability to fuse art and life, and through this fusion to break down artistic hierarchies. Trained as an engineer, he used everyday materials – sheet metal, wire, glass, cloth, string, paint – to create his unconventional sculptures. In 1931, Marcel Duchamp christened Calder’s moving sculpture the ‘mobile’; though Duchamp was by no means the first of the French avant-garde to recognize his work: Fernand Léger, Jean Cocteau, and Piet Mondrian had been interested in his work for some time.

The exhibit celebrates Calder’s ability to fuse art and life, and through this fusion to break down artistic hierarchies.

Calder first drew the discerning and general public’s fancy with his mini circus, the Cirque Calder, which he began to perform in the late 1920s. It was a production small enough to fit in a suitcase, and involved circus performers made of wood and metal who carried out their acts with the help of wire mechanisms. To watch a video of Calder performing his circus is to witness the pleasure it brought him, and the audience shares this pleasure. The whimsy of the circus, for Calder, lies in its endless possibilities for movement within time and space. His desire to capture these possibilities by creating art that meets motion – that meets life – seems to inform all his work, be it his single-line drawings, wire sculptures, or mobiles.

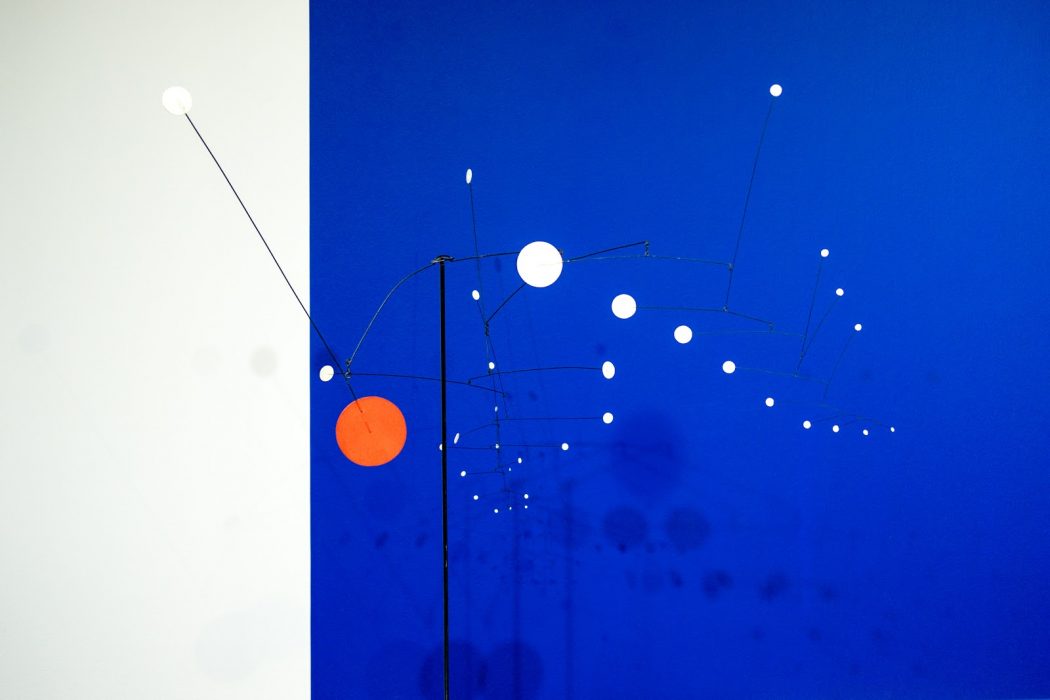

I may be an undiscerning viewer, but I kept returning to the playfulness of his art. Jean-Paul Sartre would seem to agree. In a short essay written for the artist’s 1947 exhibit, the philosopher praises the life which Calder’s creations take on, saying that “[a]t times their movements seem to have a purpose and at times they seem to have lost their train of thought along the way and lapsed into a silly swaying.” The effect is truly mesmerizing. His bold blocks of colour, each of different shape and weight, move in harmony with each other, and yet still surprise us in their trajectories’ unexpected turns.

That his art is spirited is not always immediately apparent. Many of his pieces require us first to be drawn softly in; in contemplating, we observe movement; in observing movement, we discern a pattern; a pattern only then to be broken by an unexpected turn. The honesty of his work and its demand on our stillness of spirit refresh the mind and clear from it the clutter of a thousand meaningless words and movements. To stand before one of his mobiles, is to engage in an act of almost childlike wonder. Indeed, walking through the exhibit felt like walking through a toy shop – the storybook emporium owned by the ageless gentleman with wispy hair and filled to the brim with marvelous trinkets. Yet Calder achieves the same magic with his clean lines and simple movements.

The honesty of his work and its demand on our stillness of spirit refresh the mind and clear from it the clutter of a thousand meaningless words and movements.

So why is this appealing, and what makes his art as radical now as it was then? Perhaps it’s as simple as this: the “transparent, objective, exact” nature of his art – as Léger puts it – breathes fresh air onto our cluttered, confusing, over-stimulated lives. It certainly felt like the most wonderful kind of indulgence to stand before his mobile “Red Disc and Gong” waiting for that inevitable – yet still surprising – moment when the baton was to hit the gong as each part moved in relation to the other. And then waiting for it to happen all over again.

But maybe it’s a little bit more. Maybe it’s that Calder doesn’t seek to manipulate. As Sartre points out, his creations are half mechanism, half chance. He crafts his mobiles with an undeniable mastery of shape, balance, colour, and motion, but then lets them encounter time and space – elements beyond his control. I relish this lack of desire to manipulate, and his lack of ego. I have no wish to discuss the polarization that seems to dominate the political and social spheres; yet I will say (and I think I’m in good company) that I’m tired of being pulled this way at the whims of hostile parties’ with conflicting agendas. To experience Calder’s art is to go beyond human machinations and false imitation, and to experience the beauty of a pure “absolute.”

So there you have it, perhaps not very elegantly put, but I hope it does persuade you to spend a few hours in the company of Calder’s art. In my mind at least, he has not displaced Doré, but he has certainly joined him. And beyond the few hours of quiet enchantment he has provided, he has forbidden me from making the lamentable claim that I don’t like the avant-garde. And so, redeemed some of my credibility among my art-loving friends.