On Sunday, January 26, 2020, nine people died in a helicopter crash in Calabasas, CA. The victims were John and Keri Altobelli, and their daughter Alyssa; Sarah and Payton Chester; Christina Mauser; Ara Zobayan; and Kobe Bryant and his daughter Gianna.

The crash was an inconceivable tragedy for basketball fans, for mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers everywhere. Kobe – one of the world’s few mononymous athletes – was one of the greatest basketball players in history. His accomplishments in the sport included five NBA championships and third place in the NBA’s all-time scoring list. Since his retirement in 2016, Bryant won an Oscar for the animated short film Dear Basketball based on a poem he wrote and became an advocate for women’s sports, a move influenced by his daughter Gianna’s talent and passion for basketball.

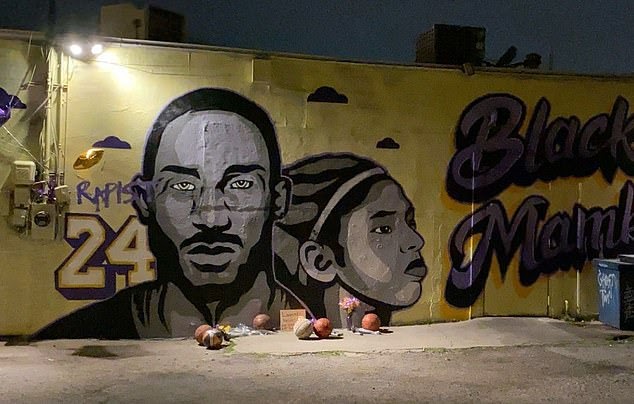

Bryant was a cultural hero, an international superstar, and, by all accounts, a wonderful and loving father to his four daughters, Natalia, Gianna, Bianka and Capri. Bryant was also an accused rapist.

Following reports of the crash, there was a predictable mass media outpouring of sympathy, expressions of heartbreak, and prayers for Bryant, the other victims, and all those personally affected. Social media was lit up with posts expressing the pain felt by many users who looked at Bryant not only as a sports legend, but also a personal inspiration and hero.

Bryant was a cultural hero, an international superstar, and, by all accounts, a wonderful and loving father […] Bryant was also an accused rapist.

Amid the flood of grief and sympathetic messages that had taken over social media in the wake of the news, Felicia Sonmez, a reporter at The Washington Post tweeted a link to a 2016 article from the Daily Beast, which detailed Bryant’s rape case. There was an instant and disturbing backlash against the tweet and the woman who posted it.

According to the reporter, who is herself a survivor of sexual assault, she received death and rape threats. One email she posted to twitter read, “Piece of f*cking sh*it. Go f*ck yourself. C*nt.” Her employer responded by suspending her from her job.

Following the original tweet, she tweeted the statement, “Any public figure is worth remembering in their totality, even if that public figure is beloved and the totality unsettling.” Due to outraged responses from many reporters at The Washington Post, the reporter, Felicia Sonmez, was reinstated after a couple of days. However, the immediate reaction of the public, as well as the hasty decision of the Post to suspend, her is worth examining.

Another woman, actress Evan Rachel Wood, also brought attention to Bryant’s past shortly after his death. She tweeted, “What has happened is tragic. I am heartbroken for Kobe’s family. He was a sports hero. He was also a rapist. And all those truths can exist simultaneously.”

Wood received a similar furious reaction from the public as Sonmez, and like Sonmez, Wood is also a survivor of sexual assault. In fact, the actress has played a significant part in the #MeToo movement and has openly detailed her own experiences with sexual assault, domestic violence and torture, in testimony to Congress. Like Sonmez, Wood tweeted a clarification of her decision later, writing, “Beloveds, this was not a condemnation or a celebration. It was a reminder that everyone will have different feelings and there is room for us all to grieve together instead of fighting. Everyone has lost. Everyone will be triggered, so please show kindness and respect to all.”

The rage that both Sonmez and Wood were subjected to following their respective tweets showcases a general social inability to accept or grapple with the fact that our heroes are not always entirely the people we want them to be. During his rise to fame and at his peak of superstardom, Kobe was a beloved and praised basketball star. So, when he was not convicted of rape, due to the victim’s eventual refusal to testify, he was able to recover and reinvent his image. His nickname “Black Mamba” was actually created by him following the rape allegations in order to refresh his reputation and win back lucrative sponsorships. Kobe was largely successful in his personal reinvention, as is shown in his later support of women’s sports and his image as a loving father and husband.

Our heroes are not always entirely the people we want them to be.

Sonmez and Wood’s tweets, as well as other statements and posts from various women on social media, are not aiming to discredit or demolish Kobe’s reputation, nor are they aiming to minimize the tragedy of his and his daughter’s passing. What the tweets are calling attention to, particularly in Wood’s case, is the widely felt pain of survivors who are left hurting and confused when a man nearly convicted of rape is exalted as an icon and hero despite his previous actions.

Shortly after Kobe’s death and Sonmez’s suspension, activist, writer, and survivor Whitney Bell wrote a statement on her Instagram page describing the complexity of her feelings, which ranged from intense grief for Kobe’s passing as well as a separation from her body brought on by her past trauma. Her feelings were echoed in the comments on her post, with many women describing their own pain and confusion as a result of their trauma and its connection to Kobe’s passing. Her goal in bringing attention to her experience was not to damage Kobe’s reputation, but rather to give a voice to a group that is largely ignored.

No one should be entirely defined by their worst actions – people can be better than their past – but it is ignorant, naïve, and offensive to claim that bringing attention to the feelings of survivors is wrong. We often see society and the media attempting to silence objecting voices when that objection forces one to recognize painful contradictions in the image of a beloved celebrity. This has happened in the cases of Michael Jackson, Woody Allen, Roman Polanski, and Kobe Bryant. In an article for The Paris Review, author Claire Dederer addresses the problem of the art of monstrous men. While she does not come to a conclusion about what exactly to do with such art, she discusses our practice of disassociating from monstrosity to the point of complete separation. Dederer claims that when we condemn the actions of someone like Woody Allen as being atrocious, we are trying to distance ourselves from our own darkness and denying the plurality of human nature. Dederer writes:

“Sure, I’m attuned to my children and thoughtful with my friends; I keep a cozy house, listen to my husband, and am reasonably kind to my parents. In everyday deed and thought, I’m a decent-enough human. But I’m something else as well, something vaguely resembling a, well, monster. The Victorians understood this feeling; it’s why they gave us the stark bifurcations of Dorian Gray, of Jekyll and Hyde. I suppose this is the human condition, this sneaking suspicion of our own badness. It lies at the heart of our fascination with people who do awful things. Something in us—in me—chimes to that awfulness, recognizes it in myself, is horrified by that recognition, and then thrills to the drama of loudly denouncing the monster in question.”

We often see society and the media attempting to silence objecting voices when that objection forces one to recognize painful contradictions in the image of a beloved celebrity.

In this context, she is talking about the condemnation of bad actions, which is certainly common and showcased clearly through the phenomenon of cancel culture. I think, however, that this view can be reversed and applied to our sometimes-willful ignorance or denial of evil actions. What Sonmez and Wood called for in their tweets is not demolition of Kobe’s legacy, but rather an insistence that we look at the good and evil aspects of a man who inspired millions, and very likely destroyed the life of one.

The thought-policing done on the side of those attacking women such as Sonmez and Wood for speaking out is simply aiming to erase the complexity of Kobe’s past in favor of a unified, positive hero myth. This absolutist rhetoric of good or evil is ultimately damaging and painful to those being attacked, or those who are left deeply questioning their feelings of pain as a result of this tragedy and its effect on their own trauma. No one person is all good or all bad. Everyone is capable of love, and most people are also capable of violence and inflicting pain, even our most beloved stars.