The second installment of Jacob Klemmer’s trilogy, reporting everything you need to know about Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival. Read the first installment here.

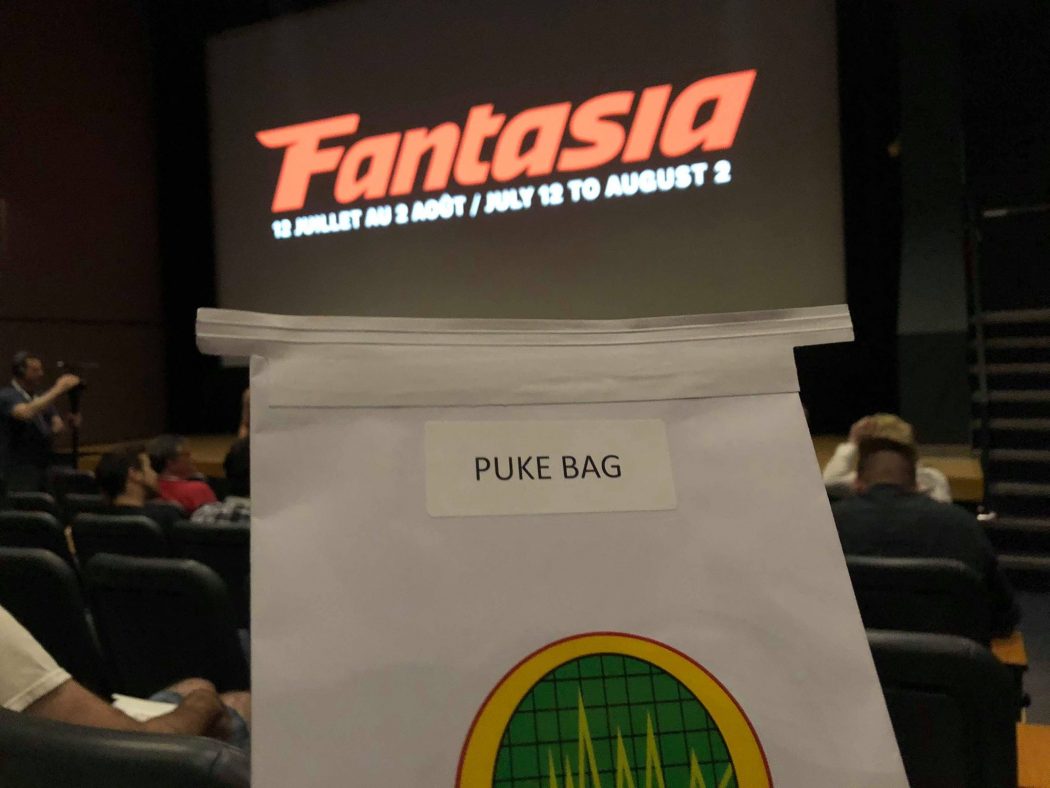

First, let’s talk about the milk. I walked into the screening of the film Relaxer by Joel Potrykus and was handed a barf bag by the staff. Before the film was introduced, the speaker chugged a small carton of milk. It all started to make sense when the film began, with its main character Abbie being challenged by his brother Cam to drink an entire gallon of milk, bottle by bottle, without first vomiting. And by the way, you’re not allowed to calm your nervous stomach by trying to pinpoint edits where they swap the bottles out offscreen, since during a certain moment it becomes… clear that this challenge was unsimulated. After the film ended there was a Q&A with Joel and actor David Dastmalchian, who plays Cam, and two audience volunteers (including film critic Mike Vanderbilt) were selected to do a live, onstage milk challenge of their very own. I’ll give it to Fantasia, this wouldn’t happen at Cannes.

It’s a fitting introduction to the film, because Relaxer is a rancid, putrid, stomach-churning, excruciating experience (Rating: 8/10) – probably the worst smelling film ever made. After Abbie completes the milk challenge he must do another challenge which becomes the meat of the film: Abbie must beat the world Pac-Man record (surpassing the unbeatable level 256), and he has 6 months, until Y2K, to do it without leaving the couch. From there, the film evolves into a kind of inverse Castaway, a survival tale of an isolated protagonist finding food and water, weathering disaster, except he never moves and could just get up at any moment if not for his sick, sick determination.

The film is similarly unwavering in its execution of this premise: it unfolds in drifting, dramatic, determined long takes, frequently in close-up, and wrings surprising tension out of sequences where Abbie must find nourishment using a grabber-arm. It’s a superb film about about pushing boundaries until they break, whether that’s a computer with only so much data, a human stomach that can only take so much lactose, or a narrative that can only stay on a couch. You will find yourself cheering its smallest gestures and thinking deeply about its smallest ideas.

Profile (Rating: 8/10) is a similarly claustrophobic narrative, keeping the ‘camera’ confined not to a couch but rather the screen of a laptop, a similar (and superior) approach to the film Unfriended. It’s about a white British journalist named Amy Whittaker who catfishes an ISIS recruiter named Bilal by pretending to be a Muslim convert under the fake name Melody Nelson. The story perfectly suits this structure: we are so submerged in Amy’s subjectivity that we can sometimes feel ourselves empathizing with Bilal, being moved by his stories and seduced by his words, and then horrified by the nonchalance with which he praises suicide bombings and mass executions.

I’d complain that a great deal of this film seems blatantly outlandish and unrealistic, until the ‘based on a true story’ title card forced me to open my phone up and discover that, yes, this really happened, and yes, there are ISIS cat memes. This film is both surreal and hyperreal, dark and hypnotizing yet undeniably hilarious, like a lolcat gif sent by an ISIS recruiter. Its ending is bombastic and the characterization is sometimes shaky, but revolutionary films are seldom perfect.

Cam (Rating: 9/10) also tells a story about the horror of internet connection and the performance of online identity. Madeline Brewer (The Handmaid’s Tale) plays Alice Ackerman, and Alice Ackerman plays ‘Lola’, a camgirl driven to become one of the most popular on her site, who’s willing to go beyond the usual striptease to do it – until she discovers that she’s been locked out of her account, which is taken over by her online persona come to life. Does all this sound exploitative? It’s not. It’s a rare film that allows the viewer this degree of identification and empathy with a sex worker, but it’s the only film I can think of that presents sex work as something to be proud of, and something that can be fulfilling (though it doesn’t shy away from portraying the risks of this job.)

The staggering empathy can be credited to the screenplay –written by Isa Mazzei, an ex-camgirl herself– which oscillates between naturalism and surrealism with ease, selling both the anxiety of the supernatural and the everyday. This film is the first feature of director Daniel Goldhaber, not that you’d know that: it’s a frighteningly determined movie. The opening scene, an in-media-res livestream performed by Lola is like a desktop movie on speed, with rapid flashes of comments, ratings, donations, breasts, and blood, breathlessly drawing the viewer in. It would easily be the best scene of the festival if not for the film’s climax, a dazzling display of screens-within-screens-within-screens.

There are echoes of Persona (1966) and Videodrome (1983), but Daniel Goldhaber is not so in debt to his influences that it prevents his own voice from flourishing. Cam’s greatest skill is integrating all of this theming and messaging into a horror film that can play to any audience, because Brewer gives the two best performances this year, wringing unexpected tension and pathos from the duel in her personae. If any film from this festival should be on your radar, it’s this one. In a post-deepfake, post-SESTA-FOSTA world, it’s not just a prescient film, it’s a necessary one.

If there is a common thread for this week at the festival, it’s that the best films all treat their characters with empathy and authenticity, and the worst films treat their characters as instruments in their plot.

Sadly, it wasn’t all revolutionary masterworks this week. Laplace’s Witch (Rating: 4/10) is easily the most boring Takashi Miike film yet, peculiar for such a famously oddball filmmaker. Miike’s formal tics (rapid montage, text over image) seem like desperate pleas to divert the viewer as they’re bored by the story. Only the comedy really registers, god knows how much is intentional.

The Nightshifter (Rating: 4/10) has more original ideas, all of which it refuses to develop. It follows a morgue worker who’s also a medium, speaking to the dead bodies that he cuts open, and from this killer premise comes a tedious narrative about a vengeful ghost doing the usual vengeful ghost things. A few nice sequences, one involving razor wire, get lost in the sludge, like the few beautiful shots that get stuck in the green-brown, anamorphic, out-of-focus photography. It’s the type of cheap, misogynistic horror film that takes great care to show us a nagging, shrill, cuckolding wife being shot in the head, expecting us to laugh and cheer.

Really though, nothing comes close to Under The Silver Lake (Rating: 5/10) in the misogyny department: it’s a film that believes a dialogue reference to the male gaze and a Rear Window poster in the main character’s bedroom are carte blanche for endless shots of asses and breasts, and scenes of women barking like dogs. Andrew Garfield plays Sam, a horny, repellant slacker who must follow a series of clues and codes in order to solve the murder of Sarah, the pretty blonde girl who lived next door to him, who he spies on with binoculars in the opening scene, which she finds endearing (the second film at Fantasia to do this.) The film evolves into a nonsense-noir picaresque, with Sam wandering into parties and artists’ houses, getting into elaborate shenanigans with men who monologue about pop culture and women who stand around to be looked at.

The film’s observations about the mass culture industry are laughable and tiresome, but it almost functions fine as sketch comedy, particularly the scenes involving Patrick Fischler’s unnamed character, a deranged cartoonist who keeps plaster molds of celebrities’ faces. It sure talks a big game about the formulaic mass culture industry, considering its thoughtless references to Hitchcock and Janet Gaynor, blatantly grafted onto the story template of Inherent Vice. Under The Silver Lake is like Ready Player One for boys in first-year film studies.

Finally, here are three really good films with fantastic titles: Satan’s Slave (Rating: 7/10) is the story of a rural Indonesian family being terrorized by a ghostly presence connected to their dead grandmother, and it plays like an Indonesian Insidious, a retro-style haunted house film that has nearly perfected the jump scare. Like all modern haunted house tales, it loses steam after the first hour or so, when it must ramp up the spooks and explain the grand satanic conspiracy, but that first hour is so dynamite that I can’t help but be excited about it.

There’s also Louder!: Can’t Hear What You’re Singin’ Wimp (Rating: 7/10), a rock and roll comedy from Japan, the most hyperactive film of the year. It’s the story of the rockstar Shing, who must use russian vocal chord dope to keep up his loud shriek, and a shy folk singer Fuka, who could be drowned out by a pin drop. It gets exhausting after the first hour, but it’s thrilling and unusual to watch comedy come this fast.

The last film I watched, an ultraviolent superhero film from Korea called The Witch Part 1: The Subversion (Rating: 7/10), follows a runaway teen Koo Ja Yoon, the former test subject of a corporation experimenting with telekinesis in orphaned children. The (slightly dull) first half leads to a bloody confrontation where both Ja Yoon and the film reveal what they’re capable of. Like all American superhero films it’s overlong, plotty and inelegant, but unlike those films the action is fabulous, and it’s anchored by a performance from Kim Da Mi (winner of the Fantasia Best Actress award) with real pathos. If there is a common thread for this week at the festival, it’s that the best films all treat their characters with empathy and authenticity, and the worst films treat their characters as instruments in their plot.