On a long car ride, experimental filmmaker David Lynch likes to play a variation of the license plate game. The highest scoring player has to find the following: a car with a license plate where the three letters spell out your initials (the letter ‘X’ is a wild card), the three numbers add up to “a number you like, and the car should be a car you like.” While writing the script for the first season of Twin Peaks, Lynch found a car with the license plate DKL999, and after tailing it for a while (some reports say hours), he was convinced that the show would be a success. According to David, if the number on the license plate is 666, you “cannot turn off your engine until you find a better number.”

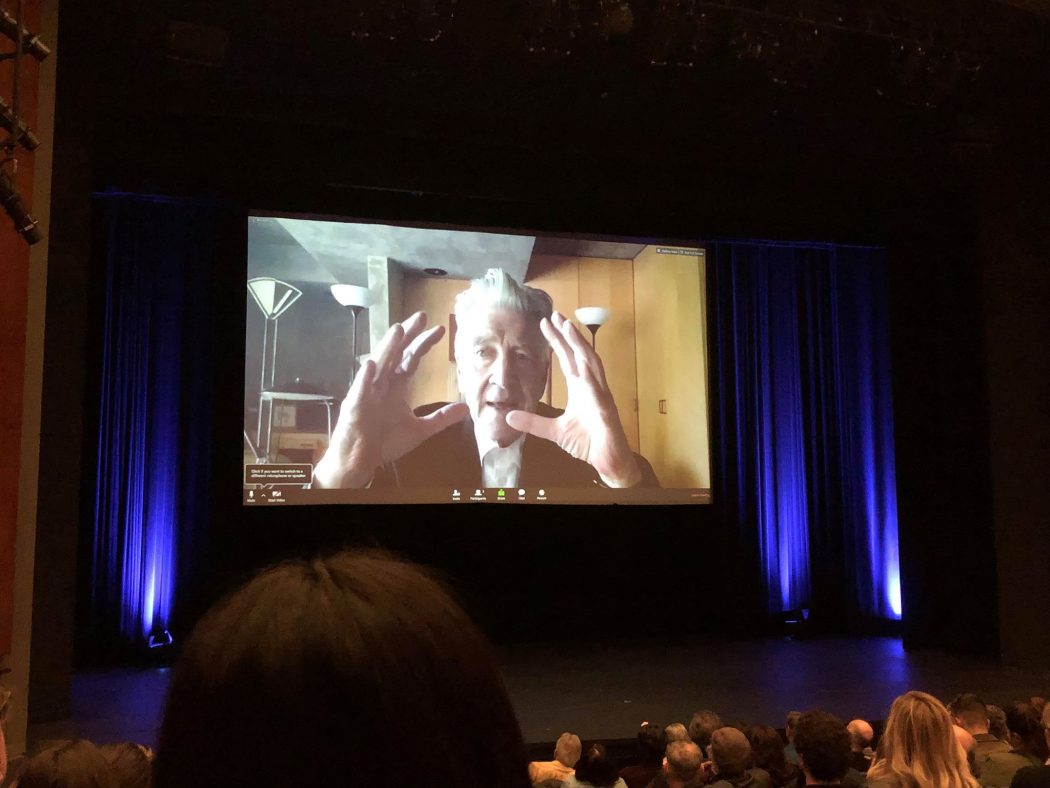

I found this out last Monday, in Concordia’s D.B. Clarke auditorium. Lynch participated in a Q&A there following a talk by Bob Roth, the president of the David Lynch Foundation. There are enough Lynchian anecdotes to fill ten articles, but I’ll just share some of my personal favourites. Lynch decided to become a filmmaker after making a painting in university of some ivy on a stone wall. Upon seeing the ivy start to move, he came to the realization of, “Ah, moving pictures!” He also designs furniture (the introductory speaker was particularly impressed by this, and quipped “What I would give to sit on a David Lynch sofa”); and he is very grateful for his four divorces because he’s “got so many great kids.” At one point, a man told Lynch that he named his child after a character from one of his films–‘Pace,’ after Laura Dern’s baby from Wild at Heart. Upon hearing that a man had named his kid after one of his most obscure characters, from one of his least-seen films, Lynch responded with only four words: “Okay, there you go.”

What I would give to sit on a David Lynch sofa.

David Lynch’s films are most famous for their mind-meltingly surreal imagery, but they are nothing without the signature Lynchian tempo: patient and brooding, with long and quiet scenes periodically interrupted by frightening bursts of noise. The effect is entrancing and startling. Lynch speaks in much the same way that his films move, with uncomfortable slowness followed by shocking insights, and almost every question beginning with a long, awkward exchange of “how are you today,” “I’m good, how are you?” The effect is only heightened by his following Bob Roth, a man who speaks with the measured, perfectly paced tone of a professional self-help guru; a voice that inspires so much trust that you can’t help but be a bit suspicious. The event, Consciousness and Creativity with Lynch and Roth, was billed equally as a talk about Transcendental Meditation and a following skype Q&A with Lynch, and so the audience divided neatly between fans interested in the filmmaker’s process and those who already practiced “TM”. Those in the former group were left with more questions than answers, not just lingering ones about Lynch’s films, but about what exactly Transcendental Meditation is.

To the best of my knowledge, the practice aims to return to the mind’s innermost state of tranquility by applying some sort of “vertical thinking.” The top of one’s mind, what Bob Roth calls the “gotta gotta mind,” is like the surface of the ocean, beset by waves and currents and tsunamis of “I gotta do this, and I gotta do that, and I gotta call her, and I gotta make a list.” By contrast, the bottom of one’s mind is the deep sea: inherently calm, where all the “big fish” are swimming. The fish are (maybe) one’s most grand ideas and profound thoughts – though Lynch also called these things “money in the vault” and “pearls on a string.” (Mixing metaphors is perhaps a side effect of repeated Transcending,)

Those in the former group were left with more questions than answers, not just lingering ones about Lynch’s films, but about what exactly Transcendental Meditation is.

All of this sounds a bit, well, vague. Lynch is notoriously unwilling to give hard answers as to the meaning of his films, so I expected as much from his talk. Bob Roth was more eager to speak about the positive effects of TM – more presentness during daily life, a reduction in feelings of anxiety and depression, and greater feelings of a brotherhood of Man – than about how it works. The dual tracks of the event, while hypnotizing, bubbled with a perverse irony that eventually became impossible to ignore: the practice of TM purports to bring one’s mind downward to an inherent peace within, and yet no filmmaker alive seems less like they have found a deep inner tranquility than David Lynch.

The price tag for learning how to do TM can be as steep as $2000, which buys you four training classes with a certified TM instructor. To its credit, Lynch’s foundation aims to bring many poor people free access to TM training, and has already brought it to underfunded schools in Chicago, some Native American tribes, and many countries overseas. All this is highlighted in a snazzy promo video (not directed by David, presumably) showing smiling children across the globe, accompanied by rousing music. But the more you consider the financial aspect of Transcendental Meditation, the more suspicious it seems, and the more suspicious its two spokespeople sound: Lynch expressed many times that by transcending twice a day, “You can’t lose!” (Except for, well, money.) Late into the evening, Bob Roth uttered the most suspicious sentence known to man: “I’m not trying to sell anybody anything!” Indeed, when the practice was founded in the 1960s, it only cost the modern equivalent of $300.

The aims of the Lynch foundation, beyond increasing access in the short term through donations, are twofold – to prove that TM is physically and mentally beneficial, and to cover the cost of TM training with the Veteran’s Affairs program, one of many American socialized healthcare half-measures. So have the benefits of TM been proven? Kind of. Bob Roth cited some studies done independently of the foundation that confirm the positive effects of transcending on one’s cardiovascular health, as well as decreasing risk for alcohol and tobacco usage (though they probably didn’t survey Lynch, who “loves tobacco” very much). Some other studies are less effusive in their praise of TM. These have suggested that the practice is merely a conditioning technique; those that are less kind call it a placebo or a cult. The jury is still out as to whether TM can work for everyone the way that it has evidently worked for Lynch.

The late sixties were a troubled time for the soul of culture, though Roth admits that our modern era is much worse, and the ailments of the modern age go much deeper than politics.

There is one element of Roth’s speech that stuck out to me in the moment and has not left my mind since. He spoke about his time volunteering for American presidential hopeful Bobby Kennedy, attending a rally for him just days before his assassination on June 8, 1968. Shortly afterward, he attended UC Berkeley and learned TM from one of his professors. Implicit in his origin story is that the journey from ground-level political organizing to meditation is an ascent to what really matters.

The late sixties were a troubled time for the soul of culture, though Roth admits that our modern era is much worse, and the ailments of the modern age go much deeper than politics. It’s true that our modern era is a stressful one: speaking personally, I’m stressed out about the impending climate catastrophe, the rising tide of white nationalism, and the lack of financial security for those my age. These are political problems, and they cannot be solved by everyone choosing to Transcend twice a day. Lynch gave a very good piece of advice in his Q&A: “Transcend twice a day, and then just go about your usual business.” He forgot to add: make your business good business.