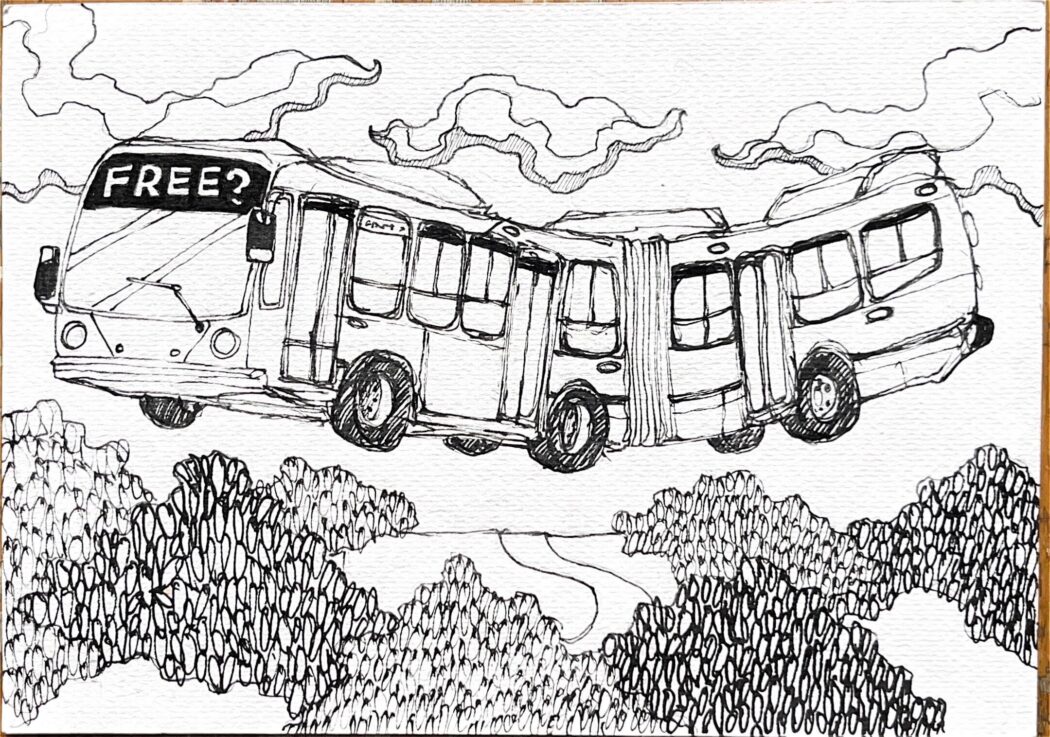

Public transportation plays a vital role in individuals’ urban lives, providing a means to travel to work, school, and elsewhere. Riding the STM in Montreal costs $3.75 a ride or $100 for a Zone A monthly pass, meaning consistent riders spend upwards of $1000 a year on transportation. For many Montrealers, this cost is a significant financial burden, especially for lower-income riders whose reliance on public transportation leads them to be disproportionately impacted. While cities worldwide have opted for reduced fares or free public transportation, including Boston, Kansas City, and Brussels, public transportation costs in Montreal remain high. In Canada, we have access to many essential services like public libraries, healthcare, and schools, funded through tax dollars. Why not extend this approach to public transportation? Making public transportation free would help reduce environmental impacts, close socioeconomic barriers, increase social mobility, boost the economy, and allow millions of riders to save hundreds of dollars annually.

Funding is one of the main concerns regarding making public transportation free. The STM has a hefty annual budget of $1.77 billion, however, without any income from fares, the money to fund its operation would decrease. We can look to Kansas City to see how they have funded their city-wide free public transportation. Before introducing its zero-dollar fare program, the city had a transit budget of $100 million, only 10% of which came from fare revenue, with the rest being publicly funded. About $10 million comes out of the city’s budget, another $500,000 from a federal grant, and they diverted $22 million from their sales tax (which was put in place at half a cent). In short, to replace fare income, the money must come from elsewhere. In order for Montreal to make the STM fare-free, they would also have to reallocate money from the city’s budget, seek federal funding, and/or introduce increased sales taxes. While an increase in tax or reallocation of funds is not ideal, the environmental and social benefit of free transportation can offset the economic cost.

Making public transportation free aids in allowing greater economic mobility, according to the mayor of Boston, Michelle Wu, who saw great success with her Route 28 free-fare pilot program. To justify the implementation of the program, Wu cited a 2015 study at Harvard that found the average commute time to work is the most closely linked factor for a family to be able to rise out of poverty.

For low-income workers, transit fares can consume a large portion of their budget, so bettering the transportation infrastructure can aid in alleviating financial burdens and providing more opportunities for upward mobility.

Furthermore, in 2022 the STM contributed $2.8 billion, supported 16, 565 related to operations and contributed $2.2 billion to GDP. Based on case studies of various cities, a reduction in public transit costs led to an increase in ridership, and therefore demand, requiring new jobs. It could be predicted that making fares free in Montreal would lead to similar outcomes, creating more jobs to keep up with the demand, and further stimulating the economy.

Also, by making transportation free, there would no longer be a need to invest in fare collection enforcement systems. These systems cost upwards of $1 billion in some cities, such as Boston’s 2021 new fare collection framework. A cost much greater than the comparatively mere $60 million made from bus fares, demonstrating money being used to enforce fares can be reallocated to fund other operations required to keep public transportation systems running. In addition to cutting costs, this would reduce social inequalities by combating discriminatory fare enforcement practices. For example, in Washington D.C., prior to the decriminalization of fare evasion, a staggering 91% of tickets were issued to Black people, despite there being no evidence showing that they evaded fares more frequently than any other racial group.

In addition to the economic benefits, implementing a free-fare program has great potential environmental impacts.

Without its high costs, people will be more inclined to take public transportation over their cars, reducing their carbon emissions. It has been seen that reduced or free-fare public transportation has led to greater ridership, including on Route 28, which saw a 38% increase. Therefore, with more individuals shifting to public transportation, environmental impacts caused by personal vehicles may be reduced. Furthermore, increased public transport usage will also decrease traffic congestion, benefiting those who continue to use cars.

Eliminating fares on public transportation, although requiring budget reallocation, leads to economic, social, and environmental benefits that ultimately outweigh any immediate financial burden.

It would help individuals combat by allowing them to spend the money they would on transit elsewhere, aid lower-income workers, allow for economic mobility, create jobs, combat social inequalities, and help the environment.