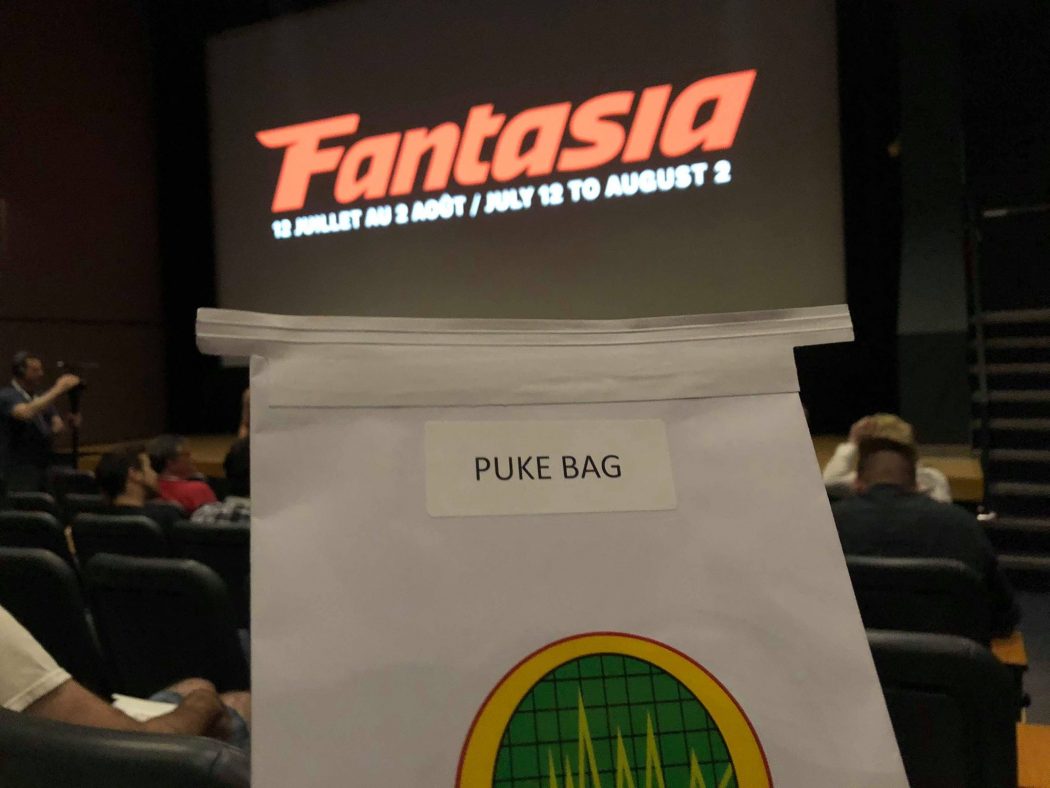

Joe Begos’ 80-minute psychedelic stunner Bliss isn’t the best Fantasia film I’ve seen, but it may be the most Fantasia. Nightmarishly gory and admirably lo-fi (shot on 16mm, in fact!), drugged out and slathered in bright lights and loud punk music, this is a film that plays to its chosen clientele, and plays to it perfectly. Yet somehow, in this film filled with vampires and goth paintings and psychedelics and flashing lights, the most shocking thing to me was my own reaction. Instead of an instantaneous gut reaction of extreme love or hate to its sensory overload and senseless brutality, I was slowly, decisively won over by a patient first act that takes the shape of a meandering L.A. character study. Dezzy, played by a stunningly good Dora Madison, is a Los Angeles painter experiencing the worst writer’s block of her life, and this period of waiting and waiting for the film to go nuts cleverly frames the upcoming ultraviolence as a displaced (and perhaps metaphorical) manner of getting over a creative slump. Come for the psychedelia, stay for the psychology.

Likewise, the first forty minutes of the Japanese drama And Your Bird Can Sing are spent waiting for something to happen, and then so is the rest. This story of a polyamourous love triangle of three Tokyo slackers is so easygoing it feels as if the film itself is on the verge of falling asleep at any moment. There are many long, immaculately photographed scenes of karaoke and concerts and waiting for the bus and sitting at cafes and getting over morning hangovers, nothing much happening, nothing much changing aside from a few sudden heartaches and the occasional random mugging. None of this sounds like praise but trust me, it is. This is a soothing and pleasurable film, and an absolute necessity when you’re watching and endless series of hyperviolent horror and action films for four weeks straight.

Come for the psychedelia, stay for the psychology.

Speaking of, how lucky that I watched Blood On Her Name just before I watched A Good Woman is Hard to Find: these two films make a terrific double bill not just because they share a premise – a tough single mother must deal with the twisted aftermath of an accidental dead body in her house – but because they succeed and fail in complementary ways. The former is set in rusty small-town America, the latter is set in a council estate in the U.K. The former is moody and grey to a fault while the latter is deadly funny – perhaps too funny for its own good. Sarah Bolger in Good Woman sells her transformation from a peaceful, overwhelmed woman into a capable killer, while Elisabeth Rohm in Blood seems perpetually in-over-her-head, both as an actor and as a character. Both films end, as expected, in violent standoffs, but the one in Blood On Her Name is more tense, more complicated, and ends on a pitch-perfect note of dark iron. By comparison, A Good Woman ends on just about the weirdest note possible. Put these two pretty-good movies together and you’d have perfection.

Or perhaps you’d get Ode to Nothing, a deliberate and stunning work, one of two films I saw at the fest that I’d call a capital-m-Masterpiece (and we’ve covered the other at length). It follows a funeral home worker named Sonya, played by Marietta Subong, a genuine superstar of the Filipino cinema, as she goes about her daily business dealings with clients, until her life is turned upside down when a body is dumped at her doorstep, her luck wildly shifting as she gets more and more involved with the body of this stranger. It’s a complex ballet of moods, deeply funny and strikingly sad, dreadful and serene, all told with cinematography and montage so precise and perfectly distanced that you’re always sure you’re seeing something spectacular, even as you question everything. As slow and methodical as this film is, it was never less than a profound joy to sit with.

When you’re sitting through a film that you know you’ll have to write about, a certain sense of creeping dread washes over you when the whole film doesn’t quite work, but isn’t quite bad enough to write badly about. The Swiss teen drama Les Particules is a halfway-psychedelic, halfway-dull film about an affectless young boy who lives in Geneva, the site of the supermassive Hadron collider, drifting through hangouts and classes and periodically dissociating. The film is empty-headed and dull, but shot in an intoxicating and bold way, such that I was never motivated to leave the theatre no matter how bored I got. The periodic dips into outright abstraction and surrealism are the film’s most productive sections, but they can’t save me from the creeping feeling that this is a fantastic short film, pointlessly lengthened.

Horror films today are far too eager to serve as their own essays.

Likewise, when a film that just isn’t quite working suddenly dips into full-tilt awfulness, a perverse sort of relief sets in even as the movie becomes more intolerable. In the case of Daniel Isn’t Real, a film about a college boy reuniting with his childhood imaginary friend to deal with his adult trauma, these unseemly moments both come in a bookstore: one in which the characters begin reciting passages verbatim from both the Book of Exodus and the Intro to Film Studies staple Ways of Seeing by John Berger, and the other wherein our main character, in a dissociative frenzy caused by his imaginary friend, picks up a book entitled, honest to God, Learning to Deal With Schizophrenia. Both scenes are intended to flesh the film out with intertextual themeing, to create a certain subtext. In fact they do: the subtext that director Adam Egypt Mortimer thinks you’re a moron, that you don’t understand his brutally obvious movie and need a little help.

All that intertextual posturing is just as misplaced as it is unnecessary; the work that encodes the most meaning into the text of this film is arguably Spider-Man 3, in that what’s intended to be a frightening and violent tale of a split mind instead becomes a showcase for awful performances, cringe-inducing scenes (worst of all the film’s two sex scenes, one of which is set in a sewer), and outfits so bad (including mesh bodysuits!) they make you wonder if the film was intended to be a comedy all along. Throw in a nakedly cynical ending, a bafflingly bad treatment of the female characters (of which the film has all three types: burdensome mothers, artists with daddy issues, and grotesque dead bodies) and some needless long takes, and you’ve got a top-to-bottom disaster, the product of everyone involved trying their hardest and doing everything wrong.

Still, it wasn’t the worst horror film I saw this week. That would have to be the psychotic Swedish nightmare Koko Di Koko Da, which begins with two parents grieving over the loss of their child on vacation, and then shows them taking their first following vacation, many years later, both of them forever changed. When a bunch of psychotic Swedes accost them in the woods, the film proceeds in Groundhog Day manner after their grisly deaths, showing endless repetitions of the same scenario, with variations resulting in no progress made, and death eternal awaiting. It is a full-blown misanthropic wallow from the first frame to the last, full of unengaging violence and empty provocation, hammering away at the same goddamn themes as every other highbrow horror film: grief is a cycle, parenthood is horror, death is inescapable, nature is sublime. I get it. Horror films today are far too eager to serve as their own essays.

On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, The Gangster, The Cop, The Devil was perhaps the most purely pleasurable experience in those four weeks: a film following the unlikely partnership between a wild cop (played by a capable Kim Mu-yeol) and a fearsome mob boss (Don Lee, in the best single performance of the entire festival) to take down a serial killer, since the boss is the only one who’s seen his face and lived to tell the tale. There are twists, turns, ample laughs and stunning sequences, all shot and edited as perfectly as you’d expect from a film with a premise this tight. Like the titular gangster and cop, this film knows what it must do, and executes it without a hitch. In case you’re not convinced: there will be an American remake of the film, with Sylvester Stallone as the cop, and Don Lee reprising his role as the gangster. Best then to see it now, so you can claim to be in on the film Before It Was Cool.

Lastly, there is Super Deluxe, an Indian film following four intersecting stories: a married couple must hide a dead body of the wife’s old college fling (who suddenly had a heart attack during their affair), three young boys must collect enough money to repair their father’s TV by any means necessary, a mother who must gather enough money to pay for a life saving operation for her child, and a woman coming back to her family after a gender transition, navigating a day with her son. It sounds like a familiar structure for a wacky, Tarantino-esque caper, but the connections between these stories are as surprising as they are cosmically random, less a hyperlink narrative than an absurdly protracted setup for cinema’s greatest-ever Brick Joke. It’s bursting with style and life, alternately deadly funny, full of tension, and full of surprising pathos. And best of all, you can watch this bugnuts soon-to-be-classic on Netflix right now if you live in Canada, so you might as well give it a go.