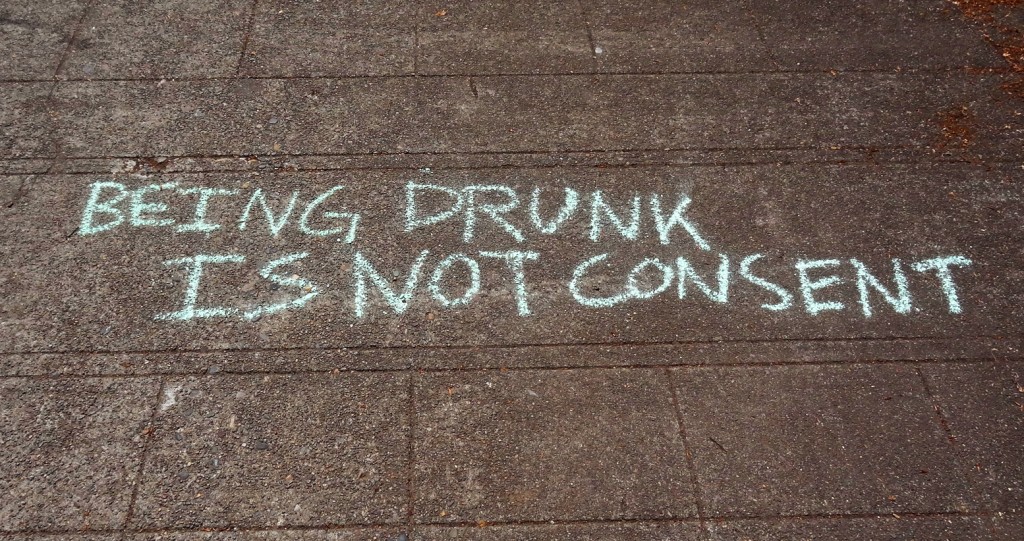

Following petitions delivered by women’s advocacy groups and sexual assault victims, California Governor Jerry Brown recently signed a bill – applicable only in colleges receiving state funding for financial aid – defining consent as an “affirmative conscious, and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity.” Gone are the days of “no means no,” whereby consent could only be disputed when one party actively refused to partake in a sexual act. Instead, by conversely declaring that “yes means yes,” the state is the first in the US to enact legislation explicitly asserting that a “lack of protest or resistance does not mean consent, nor does silence mean consent [nor does] the existence of a dating relationship […] be assumed to be an indicator of consent.”

Stephanie Thomas

Opinion Editor

The positing of “affirmative consent” in Senate Bill 967 marks a shift in the criminalization of sexual violence. No longer is the onus placed on the victim to prove they effectively communicated a refusal in a clear and understood manner to the other party. Instead, the bill makes it the responsibility of each individual who engages in sexual relations to acquire explicit consent from their partner(s) throughout the course of the experience.

On paper, affirmative consent appears as a much needed innovation. Undoubtedly, the new legislation will make it easier to hold those who commit acts of sexual violence accountable. However, I am unconvinced that a definition change – limited only to colleges, instead of including the larger community where “no means no” will remain the standard – will reduce the number of cases or guarantee additional protection from potential aggressors. Are we really claiming that a portion of those who violate others do so unwittingly, and will refrain from such behavior now that they have more rigid criteria to observe? Guilty parties may no longer be able to rely on feigning ignorance of refusal to defend their actions, but the debate will now err into the equally muddy waters of body language and alertness.

Quite frankly, it seems the focus is misplaced unless we consider that serving justice after the fact is more important than preventing sexual aggression to begin with. Imposing rules to govern the way we engage in sexual acts only serves as a paternalistic and superficial illusion of protection while it is actually meant to increase punitive ability. After all, there’s an irony to the fact educational initiatives were omitted from the bill.

Jennifer Yoon

Opinion Writer

Senate Bill 967 may be a step in the right direction to amend our deeply insufficient and – quite frankly – damaged understanding of rape culture as a society; and it should be understood as such. However, the claim by Senator Kevin De Leon, who drew up the legislation, that this bill signals a “paradigm shift” is not only far from the truth, but it is also a dangerous assertion that can do more damage than good.

The bill clarifies the culture of consent, and provides a clear-cut, agreeable definition of affirmative consent, and also places the responsibility of confirming consent on all who engage in sexual activities. Still, I worry about how this definition will be interpreted in the assortment of universities in California; the culture at Occidental College is radically different than the one at UC Los Angeles. So, I fear that this cookie-cutter measure will only worsen the situation through misinterpretation and/or misconstruction. It also follows that this bill may obstruct further efforts to change our understanding of rape culture: legislation does not necessarily determine culture, and in this case, we still have a far way to go in transforming our way of thinking.

Emma Gaudio

Opinion Contributor

California’s newly adopted “yes means yes” bill seems like something that will benefit university campuses in an age where sexual assault is at the forefront of discussions with friends, news articles and Facebook posts. The bill changes the age-old “no means no” rule of consent to “yes means yes” when campuses are investigating incidences of sexual violence.

My biggest problem with “yes means yes” is actually in its very existence. The fact that this bill was deemed necessary in the first place is aggravating. Individuals who have faced sexual assault have chronically been treated so poorly by investigators that a state finally deciding to pass a bill that changes how consent is defined is both drastic and long-overdue, but also an unfortunate reminder of the sorry state of affairs.

That being said, it’s clear that this issue continues to be so blatantly mishandled by universities if they actually think that, by changing “no” to “yes,” their problems surrounding rape allegations will suddenly be alleviated. Maybe “yes” will be the solution to the unreported sexual assaults, the poorly investigated rape cases, or even the deplorable treatment of survivors of sexual assault. Or, then again, maybe California has inadvertently created an entirely new set of problems, thereby further exacerbating the daily nightmare faced by the victims of sexual violence.

Ryan Ehrenworth

Opinion Writer

What is sexual assault? In an age where it is no longer clear what constitutes consensual sexual activity, California’s Senate Bill 967 further complicates the process of acquiring consent. As a result, no longer can non-verbal cues be understood to indicate consent; this applies during every sexual encounter and for every new sexual act, which must now be outlined and agreed to completely in advance. Even in the context of a stable sexual relationship, this bill rules that it is no longer correct to assume that the regularity of sex in the past is an indicator of consent in the future.

While I understand the premise of the bill and its efforts to make all parties more comfortable in the most intimate of moments, I think it trivializes the true nature of sexual assault. This form of violence is a heinous act of unwanted sexual behavior which can leave a person physically, emotionally and psychologically damaged. Schools such as the University of Michigan are beginning to label sexual violence as an act as trivial as “withholding sex and affection.” For the victims of rape, this is an outright insult.

Unfortunately, this legislation fails to recognize the difficulty in determining whether consent has been granted when already engaged in sexual acts. What I don’t understand is why someone who feels uncomfortable before or during a consensual sexual encounter wouldn’t grasp the opportunity to speak up, rather than asking for a verbal contract, which some argue hinders the passionate and spontaneous nature of sex. In the absence of drugs and alcohol to hinder one’s ability, I feel the responsibility should lay with the partner who feels uncomfortable to make it clear that they do not give consent, and not vice versa. Otherwise, false claims of sexual violence such as “withholding affection” will only serve to water-down the fundamental gravity of sexual assault.

The views expressed in this opinion piece are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Bull & Bear.