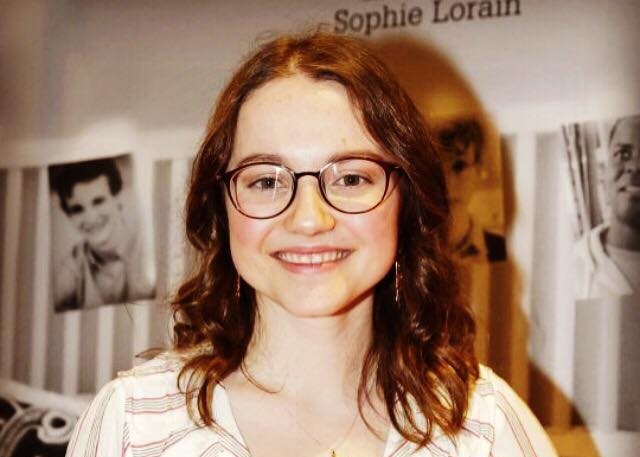

It now seems serendipitous that we decided to meet at Studio 77, a cafe in Pointe-Claire that also serves as a gallery for local artists. The Sunday morning coffee drinkers matched the clinking of their cups to their chatter as I sat myself among them and pulled out my notes. There were quite a few questions I was eager to ask Romane Denis, a 20-year-old actress and native Montrealer. For the past eleven years, Denis has played supporting roles in several Quebec television and film productions, including Subito Texto, Les Pays d’en Haut, and Charlotte a du Fun, the last of which saw her nominated for “Discovery of the Year” at the 2018 Prix Iris. Her most recent film, Les Salopes, ou le sucre naturel de la peau, directed by Renée Beaulieu, was released this autumn and screened at the Toronto International Film Festival. Preliminary greetings and latte-purchasing over, we settled in to a lengthy and lively conversation about the Quebec film industry and all it has to offer.

“We’re not afraid to tell stories that others wouldn’t dare approach,” Denis claims. And judging by her latest films, Charlotte a du fun and Les Salopes ou le sucre naturel de la peau, she does not shy away from stories that push boundaries. While both films are explorations of female sexuality, Les Salopes is more daring and controversial in its approach. Marie-Claire is a dermatologist professor as well as a wife and mother, who unashamedly indulges in lustful affairs. The audience follows — in some detail — her sexual exploits, and watches the fallout of her actions as they collide with familial and societal dynamics. Romane plays the part of Katou, Marie-Claire’s 14-year-old daughter, who struggles with her alternating desires to maintain her good-girl image and tell her parents that she has been sexually active for several years. The film poses gritty questions about lust and love, the shame women may feel regarding their sexuality, and the place of sex and fidelity in society. Proud of her role in the film, Romane asserts that “it’s really gutsy to [raise these kinds of questions] in a film right now.”

This kind of gutsiness is not an anomaly among Quebec directors, whose projects are “always one step ahead in their way of thinking.” Her answer as to why that might be is simple: there is little monetary compensation for “following the line;” Quebec film and television productions are hardly as lucrative as blockbuster Hollywood films. Putting it bluntly, Denis confirms that she and her fellow actors are “not signing million-dollar contracts, that never happens.” She points out that this grants a freedom to directors who want to pursue their vision without compromise.

Putting it bluntly, Denis confirms that she and her fellow actors are “not signing million-dollar contracts, that never happens.”

Still, the lack of funds can be frustrating. Speaking of the fame and attention Quebec director Denis Villeneuve has received in recent years, Denis is sceptical: “[Villeneuve] was one director […] The States turned to Quebec for twenty seconds, and they said ‘We love you, but we don’t want to invest money there; we want you to come here.’” She admits that the lack of recognition and funding is sometimes demoralizing, but if this is a fly in the ointment, it’s not one that would entice her to throw the whole thing out. Her feeling of pride in the content produced at home cannot be mistaken. She says: “In French, we have the expression: ‘On étire la pièce’we have absolutely no money and we do the best we can with the small amount that we’re given. I think that’s great because we have to be more creative. So we have to work with people who come up with really crazy ideas that work. And we have to do it in a short amount of time because we don’t have a lot of time, we don’t have a lot of money, we don’t have a lot of resources, we don’t have a lot of people… and we do things that are really impressive. It makes you proud.”

Besides collaborating with directors who relish in near-complete artistic freedom, Denis points to another benefit of working in an industry comparatively short on funds: people are in it for the right reasons. In other words, it’s not about “fame or stardom, [but] telling stories that other people can relate to. We offer a more relaxed way of doing things, and that’s good.” This atmosphere translates to the dynamics on set where, she says, there is certainly less of a hierarchy between the actors in front of and behind the camera than on American sets. “Here, the actors are very aware that they’re not the most important people on set,” and this allows for congeniality and a sense of a common vision amongst all those involved in the production.

In other words, it’s not about “fame or stardom, [but] telling stories that other people can relate to.

That Denis chose to spend her Sunday morning with me in a West Island cafe is testament enough not only to this “down-to-earth” quality she attributes to her fellow actors, but to the love she has of her work. She is very much part of a scene in which artistic vision shadows vain pursuit for fame and money. Her love for her community and culture clearly manifests itself in her desire to work on projects that will positively influence public discourse. She left we with this reflection: “If I don’t agree with the message of the movie, I won’t do it. But it’s rare [that that happens]. Because the work we do here is good.”