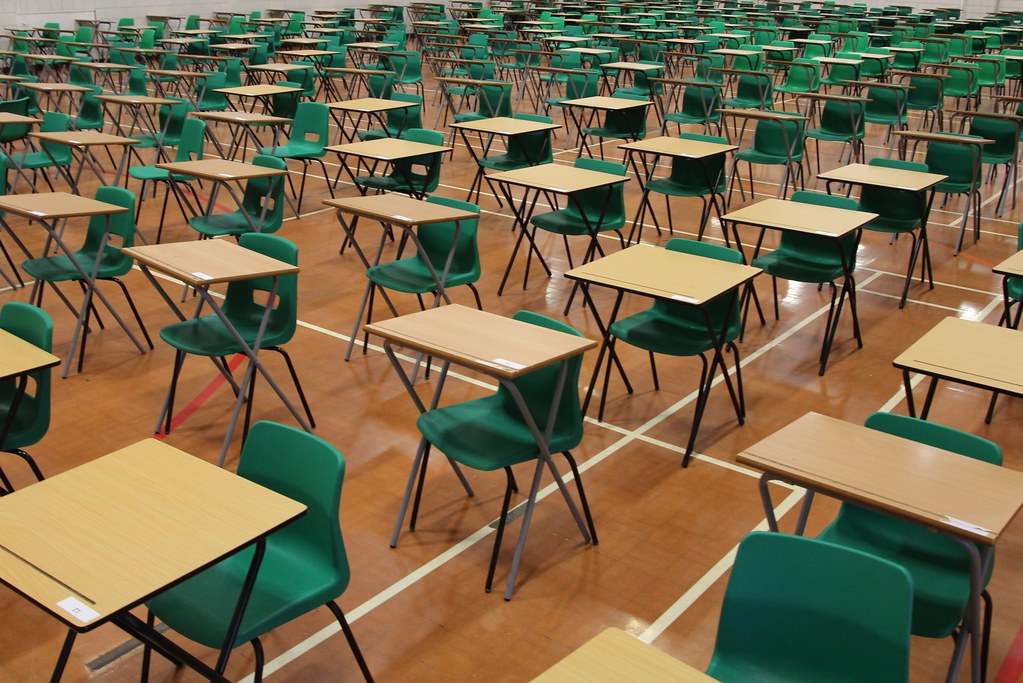

Like many students in their final year at McGill, as I attempt to balance academics, extracurriculars, work, internships and application deadlines, I find myself sleep-deprived and scrambling to meet various deadlines. Yet, as I huddle in McLennan Library in the wee hours of the night cramming for midterms, I can’t help but commiserate those particularly jaded students in their final year of studies whom, in addition to these academic and resume-building commitments, must also prepare for standardized tests.

In particular, the majority of prospective law students are in the process of preparing for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). For those unfamiliar, the LSAT is a four-hour exam required for admission to law schools accredited by the American Bar Association and Canadian common-law schools. According to the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), this entrance exam is designed “to assess key skills needed for success in law school,” such as reading comprehension, critical thinking, and logical reasoning. LSAT scores are used to predict how well students will perform in their first year of law school and, ultimately, on the bar exam. For this reason, one’s LSAT score is an integral component of the law school admissions process, often weighing equally, if not more, than their grade point average (GPA).

So, just how much time and money is involved in preparing for the LSAT? The Princeton Review recommends two hundred and fifty to three hundred hours of studying over a three-month period, which is equivalent to approximately twenty hours per week. In addition to gruelling months of due diligence in preparation for this entrance exam, law applicants are expected to spend a significant amount of money to achieve their full potential. Registering for the LSAT costs over three hundred dollars, and approximately one out of every four candidates take the LSAT more than once. Review books and practice tests cost at least 100 dollars. Moreover, many students enroll in LSAT courses, which cost approximately 1,500 dollars, and use 7sage, an online study tool that costs $700 USD, in order to raise their scores from their initial timed diagnostic. With all these costs considered, the price of taking the LSAT ranges from four hundred to three thousand dollars. Evidently, the LSAT’s impose additional strain on prospective law students, during an already highly stressful admissions process.

I don’t believe that the LSAT should be used to determine law-school acceptance precisely because it is not predictive of future legal success and is skewed towards those who can afford the financial costs and the time-commitment that is demanded of this exam.

While the LSAT is arguably predictive of first-year law school grades, it does not guarantee further legal success, as many students adapt to the techniques of law school exam writing therefrom. A recent report released by Law School Transparency (LST) itself refutes the claim that the LSAT predicts the probability of passing the bar. The study found that students from one law school who had LSAT scores in the 147-149 range had a bar pass rate of 57 percent, while a cohort of students attending another law school had a pass rate of 23 percent. Evidently, many alternative factors significantly affect bar passage rates other than LSAT scores. According to another study, GPA, college quality, choice of major, and work experience are more significant and reliable predictors of law school success and bar passage rate.

The LSAT is also unfairly stacked against linguistic minorities and those from less affluent backgrounds.

In addition, while the LSAT measures logical skills, it cannot possibly quantify other skills that are integral to successful performance in the practice of law. Examples of such skills include work ethic, intuition, humility, self-confidence, integrity, emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills. While syntactic skills are undoubtedly valuable, these latter qualities are salient in the formation of lawyers that are sought for in today’s society. I believe that other facets of the admission application, such as reference letters, interviews and curriculum vitae are appropriate devices for evaluating the attributes of candidates, and in turn of predicting success in the legal profession.

The LSAT is also unfairly stacked against linguistic minorities and those from less affluent backgrounds. On such standardized tests, which are offered only in English, native English speakers consistently outscore those for whom English is a second language. Moreover, LSAT scores are directly correlated with family income. Applicants who can afford to enroll in review courses, to pay for tutors, to buy a multitude of books and practice tests, not to mention having the privileged background to be able to write the LSAT more than once, are clearly at an advantage than the thousands of candidates who can’t. The time-commitment for preparing for the LSAT will also inevitably be a greater sacrifice to those who must work to cover the costs of their education.

These financial and time-commitment barriers preclude certain students from even attempting to apply to law school, let alone securing a spot.

In order to be competitive, less privileged individuals will have to make a choice: do they work extra hours to cover the imposing costs, or do they work less in order to attribute the required time to study? These financial and time-commitment barriers preclude certain students from even attempting to apply to law school, let alone securing a spot. Moreover, just because affluent students score higher on the LSAT, this does not necessarily engender more successful law school performance. According to a recent Harvard study, students with lower LSAT scores and with low socioeconomic status became more successful on average than more affluent students who performed better on this exam. This suggests that a student’s drive to succeed is a better indicator of future success than the mere outcome of a standardized test.

The LSAT fundamentally disadvantages linguistic minorities and those from lower class backgrounds. Instead of just the LSAT, law schools should adopt a more holistic approach based on GPA, curriculum vitae, interview and reference letters as a more fair and reliable measure of law school success and beyond. In order to pave the way for a legitimately diverse student body, law school admissions must end the practice of these limiting, inaccessible standardized tests.