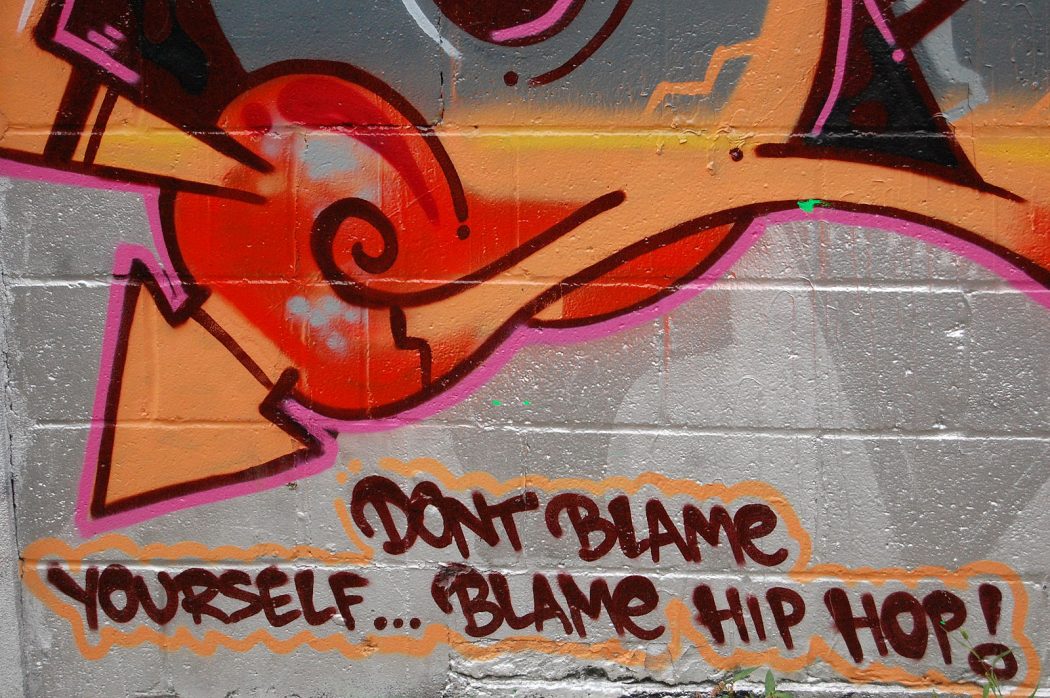

Skipping through the music on my phone, it’s hard to imagine that “SICKO MODE” by Travis Scott and Drake shares any of the same musical or lyrical qualities as anything by The Pharcyde. While both have their fair share of misogynistic lyrics and describe a rags-to-riches journey, it’s as if the 2010s have marked a transition from old school hip-hop to a new kind of auto-tune-saturated hybrid. Beyond the changes in tempo and sound, modern (read: post-2010) hip-hop seems less attentive than its predecessors to the genre’s history of providing a vocal outlet for America’s underrepresented demographics. Given the current moment’s rapidly changing social circumstances and the fact that musical genres develop over time, inevitably aspects of hip-hop music were bound to change. But for a genre so associated with African-American youth culture in the United States and rooted in that group’s expression, I think it’s important for modern day artists to pay tribute to the genre’s history rather than continuing to widen the gap between past and present.

To understand the historical implications of hip-hop, we first need to look at its origins and path to popularity. While it is difficult to attach a genre to a single moment and creator, hip-hop’s creation is often attributed to Clive Campbell—better known as DJ Kool Herc. Born in Jamaica, Campbell immigrated to the Bronx at 11, bringing with him ‘toasting’, a practice in which DJs speak over their records in a not-quite-lyrical manner; this method shows up in the early work of artists such as the Sugar Hill Gang, Run-D.M.C and DJ Kool Herc himself. After showcasing these performance techniques at his sister’s birthday party, hip-hop began to spread in the Bronx and the other boroughs of New York City.

But for a genre so associated with African-American youth culture in the United States and rooted in that group’s expression, I think it’s important for modern day artists to pay tribute to the genre’s history rather than continuing to widen the gap between past and present.

The music was innovative both for its form and content. The early 70s is often considered the decade of classic pop and rock, celebrating top-of the charts artists such as Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. With hip-hop’s repetitive beats and speech-like vocals, the genre dramatically broke with the verse-chorus work of other popular genres.

Hip-hop owes much of its success to the messages it conveyed and the voices it granted to the formerly voiceless. As crime rates and gang violence increased beginning in the 1960s and 70s under the backdrop of the War on Drugs, minority communities were disproportionately harmed. It was here that hip-hop found its largest proponents. In particular, the genre offered African-American youth a means of expressing their stories and challenges in a social environment often dismissive of narratives outside of the white and wealthy.

Hip-hop owes much of its success to the messages it conveyed and the voices it granted to the formerly voiceless.

Since hip-hop’s founding decades, the genre has expanded beyond its initial associations with New York African-American culture to encompass a variety of sub-genres and artists hailing from different backgrounds. We’ve seen everything from conscious rap, popularized by Mos Def and Common; gangsta rap, typically associated with Ice Cube and Snoop Dogg; to more contemporary categories like trap or xan rap. Despite its modest origins, hip-hop is now a global phenomena, where a quick Google search tells us that out of the top ten Billboard songs of 2018, as many as four fall into the hip-hop/rap category.

Taking a look at the most popular hip-hop artists of our generation, though, it’s easy to see that artists like 21 Savage or Ski Mask the Slump God sound completely different from what the likes of the Sugarhill Gang were rapping about in “Rapper’s Delight.” In his seminal song, “XO Tour Llif3”, which is as hard to understand as it is to type, Lil Uzi Vert gives us lines like, “I’m quite alright, I’m quite alright/And my money’s right” or “Xanny, help the pain, yeah/Please, Xanny, make it go away.” In many ways, Uzi Vert’s lyrics are indicative of just how much the genre has shifted; while hip-hop remains, and will likely always remain, a forum for engaging with topics like addiction, social injustice, and relationships, these themes also seem increasingly commercialized. While I do not intend to dismiss the difficulties experienced by modern day rappers, it sometimes feels like popular rap songs are conscious of an unspoken checklist, trying to hit their quota of Xanax and sex references to guarantee them a spot in the world of commercially-geared music.

I’m not proposing that contemporary rappers reconstruct their music to fit with our nostalgic perceptions of early hip-hop. To do so would negate years of increasing social acceptance and development within the genre and culture more broadly.

While it’s easy to see that there is money to be made by hip-hop, its original purpose and function is undermined when its driving purpose is profitability. There seems something appropriative about taking a long-standing part of African-American culture and exploiting it for commercial gain with the intention of sharing one’s personal struggles as an artist merely as an afterthought. This becomes especially controversial with white artists, who can seem quick to forget that hip-hop was often looked down upon among white Americans in the ‘80s and ‘90s. To continue in the name of commercial gain suggests a false sense of social superiority, asserting that we have overcome the hardships of the past and that music now can be divorced from its earlier forms.

I’m not proposing that contemporary rappers reconstruct their music to fit with our nostalgic perceptions of early hip-hop. To do so would negate years of increasing social acceptance and development within the genre and culture more broadly. What I am suggesting, though, is that artists acknowledge the genre’s past and the struggles of the few that gave rise to hip-hop, whether through artists’ personal motivations behind creating music, the sound quality they achieve, or lyrical messages they promote. Powerhouse figures like Kendrick Lamar and Earl Sweatshirt, who hail the past in songs like “Compton” or “Mantra,” show us that the present can draw on the past and that DJ Kool Herc’s legacy is not yet dead.