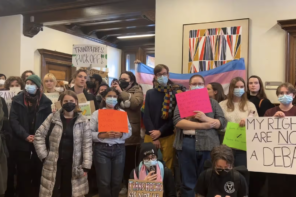

Almost simultaneously with Pauline Marois declaring the Summit on Higher Education a success, protesters were congregating in Victoria Square by the thousands. The rally was instantly declared illegal as the SPVM was not informed of the protest route, setting the stage for an afternoon replete with riot police, 13 arrests, tear gas, and countless snowballs thrown. At issue was the announcement that tuition fees in the province would not be held constant but would rather be set to increase by a small amount each year for a non-specified period, at an average of 3 percent.

Almost simultaneously with Pauline Marois declaring the Summit on Higher Education a success, protesters were congregating in Victoria Square by the thousands. The rally was instantly declared illegal as the SPVM was not informed of the protest route, setting the stage for an afternoon replete with riot police, 13 arrests, tear gas, and countless snowballs thrown. At issue was the announcement that tuition fees in the province would not be held constant but would rather be set to increase by a small amount each year for a non-specified period, at an average of 3 percent.

This projection is based on the work of Pierre Fortin, a celebrated Quebec economist who has long acted as an occasional advisor to the provincial and federal governments. Dr. Fortin, a professor emeritus in Economics at UQAM and former president of the Canadian Economics Association, proposed indexation as the best way to generate additional income, since outright hikes were off the table and freezing tuition had been declared financially unfeasible.

Fortin presented a working paper entitled “Accessibilité et indexation: les enjeux” (Accessibility and indexation: the stakes) at the pre-summit. In it he identified the three most plausible of many indexation scenarios, with average increases projected for each. Tuition could be pegged to either inflation at roughly 2 percent, disposable income at 3 percent, or university operating costs at 3.5 percent.

While the PQ eventually settled on indexing to disposable income, Fortin had actually advocated for indexing tuition to operating costs, which increase at a faster rate, as in his view it would keep tuition in line with the actual cost of education.

The significant decrease in the size of the cuts is a measure to prevent the same kind of shock that triggered widespread demonstrations last year. “If you increase tuition at three per cent a year, no one will notice,” said Fortin at the pre-summit. “But if you have a freeze followed by a 30 percent increase in 10 years, it leads to social instability. Really, a freeze could lead to another crisis.”

This signifies the breaking of their campaign promise to freeze tuition altogether, but the dollar value is still comparatively small: Tuition is projected by most to increase by $70-75 each year, totalling $420 by 2018, as opposed to the previously proposed increase of $1625 within the same period that the PQ cancelled on its first day in office in September 2012. The PQ is selling the indexation as a different sort of freeze, with costs growing relative to students’ ability to pay.

These figures are based on Fortin’s econometric projections of the average yearly increase in Quebec household disposable income. Many media outlets are incorrectly reporting that the increase will be a flat three percent each year, but bumps to tuition will actually fluctuate based on economic conditions. “Do not be surprised if the indexation is 2.1 percent one year and 3.2 percent the next,” Marois explained at the summit. The actual value of these increases remains to be seen.

The PQ decided to take action without reaching a consensus, a move that disappointed the student groups in attendance. “We can continue to reflect but cannot put this decision off forever; this summit must reach a conclusion,” Marois said. “Do we want to spend another six months, a year, spinning in circles? A consensus would be nice but waiting is not the solution.” The Premier was unapologetic: “The responsibility of the government is to decide, and I decided,” she said after the summit.

The more militant student group ASSÉ elected to boycott the summit due to the fact that the PQ had refused to consider totally free tuition as an option. Instead, the group organized the largest protest the city has seen since the summer of 2012. “Students will be there to remind the government that they didn’t take part in six months of strikes to get an increase in tuition,” said ASSÉ spokesman Jérémie Bédard-Wien during the mass protest on February 26th.

Other student groups had a more mixed outlook. “We are disappointed to see that the government went ahead despite the absence of a consensus, but students aren’t leaving empty-handed,” commented FEUQ President Martine Desjardins. While tuition will be increasing, that also came with the promise to reconsider many of the mandatory fees charged by schools and to expand projects providing student aid.

In spite of less solid support from organized groups, the student movement seems to have gained a life of its own: another demonstration on March 6th saw 62 people arrested, including one man wielding two Molotov cocktails. ASSÉ is not claiming involvement with this particular round of protests, but did promote it on its Facebook page. “The students have taken it upon themselves to continue the movement,” said Bédard-Wien.

So was the Summit on Higher Education a success? Time will reveal the impact of these moves on Marois’ support from the mobilized student electorate for whom she donned a red felt square. “We have succeeded in putting the confrontations behind us,” proclaimed Marois in the summit’s closing ceremonies. “The social crisis is behind us.” The truth of this remains to be seen.