It was always a nerve-wracking experience to check up on After School. Upon pulling it up on my iPod touch, I was met with a cesspool of adolescent angst, extravagant lies, and rude comments. It was virtually a Craigslist missed connections page for middle school lovers, and it was the hot topic of the student body.

New gossip surrounding the app surfaced each day, the anonymity of its content fueled our obsession even further. In time, us middle schoolers morphed into detectives, sleuthing tirelessly to find out exactly who called Heather a hottie the night before.

We had grown up in an age defined by the internet and social media. Schoolteachers and educational programs constantly berated us with warnings of false anonymity online. Despite our upbringing emphasizing digital caution and safety, After School offered us a platform that, in our young eyes, made us completely invisible to our audience. We could freely broadcast the pubescent thoughts we desperately wanted to share without anyone knowing their origin. Essentially, we could get a taste of the spotlight without having to stand directly in it. It was the perfect way to vent for tweens who wished only to fit in.

As we matured and changed, so did our social media platforms. After School came and went and in its place rose apps like Yik Yak, Whisper, and Secret. All of which utilized similar interfaces, which demonstrates a completely anonymous way of posting pictures, chats, and most abundantly, confessions.

In our lectures, in our dormitories, on our class Facebook pages, we live incognito.

Although the hallways here are filled with young adults rather than adolescents, McGill is home to similar anonymity. A natural consequence of being a large university, the majority of students meander through lecture halls and Facebook groups anonymously. Simply try walking up McTavish; you may run into one, two familiar faces within a sea of strangers. Online, McGill students can post their thoughts publicly, secure that eighty percent of those who scroll past our profiles won’t recognize our face. In our lectures, in our dormitories, on our class Facebook pages, we live incognito.

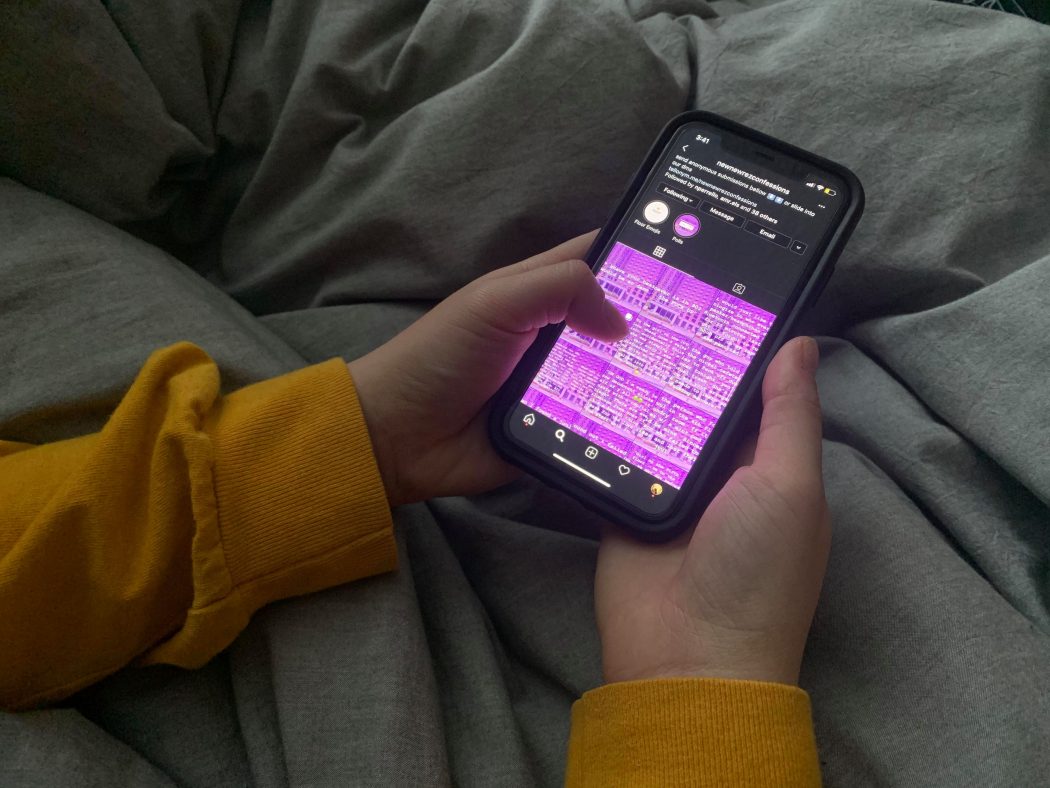

And yet, there exists an even further grasp for anonymity. Recently, my roommate suggested that I follow an Instagram “confessions” account belonging to someone (anonymously, of course) from New Residence Hall, our residence. Curiously, I opened the account, and never before have I been brought back to my middle school days than when I witnessed the account @newnewrezconfessions.

Astonishingly, the confessions on the page resembled much of what my young eyes had seen on After School. Hapless first-years had filled the account with outrageous stories, sexual fantasies, and lengthy descriptions of romantic interests. People were admitting to things quite unbelievable and so fascinatingly disgusting; almost everything listed on the page would embarrass someone tremendously if they dared to say it aloud.

If a confession is made but there is no name attached to it, was there really a confession in the first place?

And yet, there it all was, laid bare online and in the open, vulnerable for anyone to stumble upon. The New Rez account isn’t alone either; there exist numerous other anonymous McGill confessions pages on Instagram, including @solinhallconfessional, @mcgillconfesses, and even @rvcspicyconfessions1 for our school cafeteria. All are public accounts, but beware before visiting, as some posts are quite profane.

What exactly is the appeal of these accounts? Why would people choose to make these confessions if no one will know where they are coming from? If a confession is made but there is no name attached to it, was there really a confession in the first place?

Perhaps I am reading too far into the philosophy of anonymous posting. It’s plausible that many of the confessions are mere vents. I can admit that sometimes just putting a thought out into the world is enough to stop it from bouncing off the walls of your mind. But there is another level of these posts that makes me question their seemingly innocent purpose of blowing off some steam.

The amount of potential humiliation in some of the more sexual or rude confessions on these accounts is staggering. In a few of the posts on @newnewrezconfessions, anonymous authors use real names to address people, or they provide a description so detailed that someone could easily recognize the post is about them. Even the posts that are quite obviously fabrications would cause someone’s face to flush with embarrassment if they were to be exposed.

This strain of anonymous posts — the awkward, cringe-worthy ones — is what confuses me the most. I find it difficult to accept that someone who is proposing a threesome with two guys in their building is plainly trying to get something random off their chest. It leads me to ponder whether these platforms are truly serving their intended purpose of a place to share thoughts without direct judgment, or just as a destination for attention-seeking trolls?

Scholars and charities alike have pointed out countless times the role digital anonymity plays in exacerbating the issue of cyberbullying among younger children.

As I explore the anonymous confession accounts of McGill further, I start to believe that anonymity on social media, especially in a youthful setting, could be causing more damage than relief.

As we’ve all learned from years of internet use warnings, it is always easier to say something when no one knows it is you who is saying it. Scholars and charities alike have pointed out countless times the role digital anonymity plays in exacerbating the issue of cyberbullying among younger children. In fact, After School has been under fire in the past for its leniency with violent or threatening posts against users, and its more contemporary incarnation Yik Yak has also faced similar accusations.

Of course, with college students, the concern of cyberbullying may not be as pressing as it is with grade schoolers, but the content of much of these confessions may be reaching a point that surpasses simple fun and games. Racial stereotypes and sexual targeting make their way into these pages disguised as “confessions” or “jokes.”

The general attitude of being real or ‘spilling tea’ that these accounts adopt makes it easy to say hurtful or incriminating things. By adding anonymity into the picture, it becomes even easier to harm others. Despite seeming like innocent Instagram accounts for students searching for a laugh , it’s possible that the sense of distance the confessors feel from their words could result in personal pain.