Over the past few years, there has been a trend that has become more visible in the global discourse surrounding tragedies: it’s becoming a contest. The conversation surrounding these tragedies rarely remains focused on the circumstances and consequences of these events following the initial 24-hour news cycle. Nowhere was this better on display than last April, when, with only a week between each other, The Notre Dame cathedral in Paris burned down and a series of targeted suicide bombings struck multiple churches and high-end hotels in Sri Lanka.

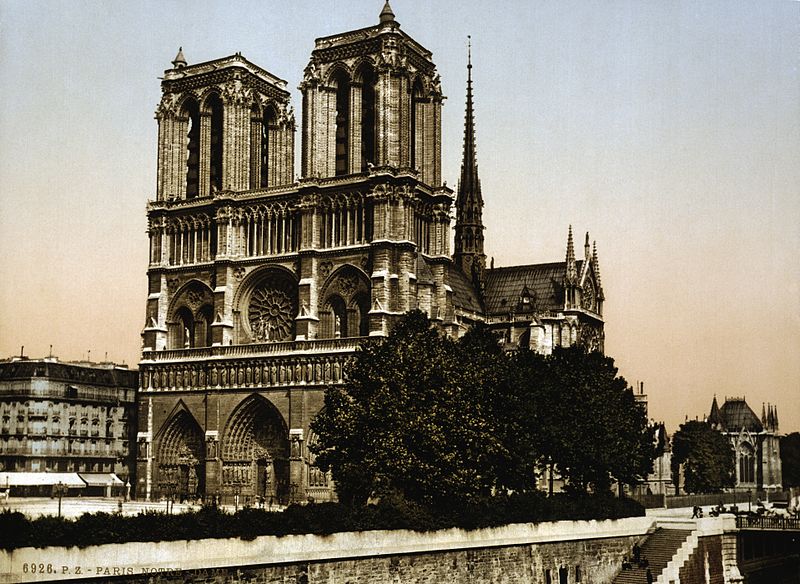

Before this goes any further, let’s review the facts. On April 15th, a fire ravaged the famous Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, with the blazes destroying its roof and spire. The fire raged for nine hours and two policemen and a firefighter were injured. According to the presidential cultural heritage envoy, Stephane Bern, in the day and a half following the fire, 880 million euros had been raised for the reconstruction of Notre Dame from all corners of the world. The bulk of the donations, however, have come primarily from wealthy French families, namely Bernard Arnault, the owner of LVMH; the Bettencourt-Meyer family, who are the largest shareholders in the French brand L’ Oreal; and Francois- Henri Pinault, who heads the luxury group Kering. Collectively, their donations amounted to 500 million euros.

With regard to Sri Lanka, the attacks began on Easter Sunday, when a bomb went off in St Anthony’s Shrine, a Catholic church. Two more churches, the St Sebastian Catholic church and the Protestant Zion church, were later bombed. Following the strikes on the churches, three high-end hotels were bombed: the Shangri La, the Kingsbury and the Cinnamon Grand. Two final blasts occurred at a guest house and a home in Colombo. The death toll by the end of the attacks stood at 253, with the majority of the casualties being Sri Lankans and about a dozen being foreigners.

The succeeding news coverage reflected the different nature of the tragedies. Notre Dame was the first to occur and was followed by an outpouring of support to the French for the loss of their cultural landmark. Following the fire itself, the next few days of news related to Notre Dame consisted of myriad articles relating the causes and effects of the fire, the history of the Cathedral, its potential restoration, and the large sums of money donated to the restoration of the church.

In contrast, coverage on Sri Lanka, which happened about a week after Notre Dame, focused on the death toll, the circumstances of the attacks, the people affected and those potentially responsible. Coverage was worldwide, with media houses in both the global North and South dedicating weeks of articles, opinion pieces and infographics to the two events, and with world leaders offering their condolences to all affected. However, through a comparison of the popular reactions to the events, we can clearly see the phenomenon that is the “tragedy Olympics.”

The discourse on Sri Lanka following the attack was centred not primarily on the attack itself, nor on its victims but on its standing in relation to Notre Dame.

The discourse on Sri Lanka following the attack was centred neither primarily on the attack itself, nor on its victims, but on its standing in relation to Notre Dame. In my opinion, this journalistic bent happened for two main reasons. The first is that the Notre Dame tragedy had occurred so recently and the second is that the donations that Notre Dame received for the reconstruction effort were disproportionately large, especially when compared to those the victims of the bombings were receiving. Social media that day was awash with knee-jerk reaction posts comparing the reactions globally; people criticized the outpouring of support to Notre Dame and the general lack of reciprocity for the victims of Sri Lanka. The conversation ceased to be about the actual attack in Sri Lanka and instead for the most part relegated Sri Lanka to a “what about” scenario. Instead of affording the event the respect it should have commanded, the media debased it to a mere comparison. Although the anger was valid, it took away from the horror that the reality of the event encapsulated, as the bombings ceased to be viewed as tragedies in and of themselves.

I am of the mind that serious discussions need to be had about the way in which the global community chooses to address issues in the global North and South, and the obvious disparities present there.

I am of the mind that serious discussions need to be had about the way in which the global community chooses to address issues in the global North and South and the obvious disparities present there. I also believe that to immediately take the suffering of hundreds of people and to relegate it to a comparison with another tragedy of severely lower magnitude in terms of loss of life is reductionist. Indeed, it denies the bombing the autonomy that is so crucial in creating support for those affected, and to an extent sidelines the death of hundreds in favour of a discussion on billionaire Frenchmen and the size of the cheques they chose to write. The Notre Dame fire was not compared to another tragedy that had happened prior, and this—to a large degree—enabled the conversation to be centred on the actual fire itself. When the Sri Lanka bombings occurred, they were already competing for international attention with the fire the previous week, and so to predicate the entire discourse on Sri Lanka on the greater support for Paris harmed more than it helped.

And this is not to say that I do not feel issues do need to be amplified to bring attention and support to those who need it. I simply believe that an issue does not need to be subjugated to another for it to become important. The massive amount of donations raised for Paris in such a short stretch of time does raise questions about why this level of outpouring support is not felt for other horrific situations; however, it should not factor into the discussion on the deaths of 253 people in another country. The objective for the media in instances such as these should be to find a way to amplify the issue for the issue’s own sake, and with Sri Lanka’s disastrously high casualties, that would not have been too hard. Instead of focusing our discourse on the disparities between two events that severely differ in scale and magnitude, we should amplify these tragedies individually. We can let people know what is going on, post links to donation pages and blood drives, make our objective to make the voices and experiences of the people suffering heard, and not relegate them to a comparison.

Instead of focusing our discourse on the disparities between two events that severely differ in scale and magnitude, we should amplify these tragedies individually.

An excellent example of an issue being amplified without having to be subjected to another is the case of Sudan. Over the past few months, there has been a lively social media campaign to raise awareness for the atrocities being committed by the military government in Sudan; because the discourse centred on Sudan only, massive amounts of support and awareness have been raised towards the actual problem at hand. It’s something that can be done, even for issues that occur in the developing world. This example only shows that it’s not exclusive to issues in the West, and thus we should strive to make this a reality for all tragedies instead of ranking and ordering them for the sake of “what about” arguments.

And finally, since we’re talking about exclusivity, let’s also recognize that one need not exclusively show sympathy for one event at a time. Voicing support for the fire in Paris does not bar someone from going on to express sympathy for the victims of Sri Lanka. Nothing bars us from donating to a cause we see fit and nothing prevents us from caring about more than one issue at a time.

In instances where we encounter these global tragedies, we should hold back from participating in a dead sprint at the “tragedy Olympics.” Let’s instead take a step back and see what we can do to treat each individual issue with the respect it deserves.

Nice piece! The framing of a sensitive and complex association of events into a thought provoking quick read is impressive.

Thanks for writing

this is so tone deaf – wow